Special

Operation

of a Nuclear

Submarine

TRUE STORY

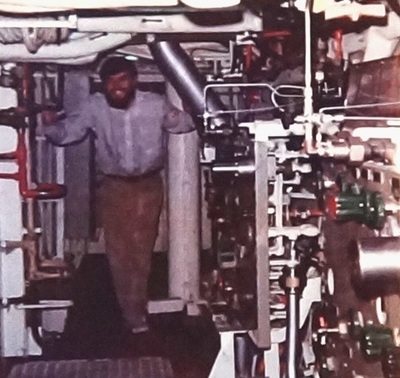

Author at navy second-class dive school.

Author at navy second-class dive school.

I was a diver in the navy from 1971-1975, and all us divers on our submarine had received top secret clearances. I was not a SEAL but a saturation diver, trained for deep dives and extended periods of time. I made five saturation dives in the navy and three of them lasted one week each - explained later.

About eight years ago, I corresponded a few times with John Piña Craven. He was an officer in the US Navy and, in fact, was the Chief Scientist of the Special Projects Office of the United States Navy. He has a bachelor’s degree from Cornell University, a master’s of science degree from California Institute of Technology, a PhD from University of Iowa, and a law degree from George Washington University.

Craven published the book The Silent War: The Cold War Battle Beneath the Sea. He guided the navy’s undersea special-projects operations during the Cold War, and we owe him a debt of gratitude for his service.

In his book, he talks about the project I was involved in, and he writes about it in the first person (not hearsay). How he was able to do this without crossing over the legal line, I cannot tell, but aside from being a scientist, he was also a lawyer. I will quote him on the secret parts.

The nuclear submarine USS Halibut, while it was still in service, had the distinction of being the most highly decorated submarine of the post-WWII era. What follows is somewhat technical, but there is a point to it all. I joined the navy as a reservist and originally had a two-year active-duty obligation, but I kept extending my time so I could attend three navy diving schools. In all, I served nearly five years on active duty and more than a year reserve time. The navy sent me to two diving schools in Washington, D.C.: second-class dive school, a ten-week diving and salvage school; and first-class dive school, which lasted seventeen-weeks. I graduated top in my class from both. In addition, I graduated fourth in my class from the navy's saturation dive school at Point Loma, California, which was about a fourteen-week program.

About eight years ago, I corresponded a few times with John Piña Craven. He was an officer in the US Navy and, in fact, was the Chief Scientist of the Special Projects Office of the United States Navy. He has a bachelor’s degree from Cornell University, a master’s of science degree from California Institute of Technology, a PhD from University of Iowa, and a law degree from George Washington University.

Craven published the book The Silent War: The Cold War Battle Beneath the Sea. He guided the navy’s undersea special-projects operations during the Cold War, and we owe him a debt of gratitude for his service.

In his book, he talks about the project I was involved in, and he writes about it in the first person (not hearsay). How he was able to do this without crossing over the legal line, I cannot tell, but aside from being a scientist, he was also a lawyer. I will quote him on the secret parts.

The nuclear submarine USS Halibut, while it was still in service, had the distinction of being the most highly decorated submarine of the post-WWII era. What follows is somewhat technical, but there is a point to it all. I joined the navy as a reservist and originally had a two-year active-duty obligation, but I kept extending my time so I could attend three navy diving schools. In all, I served nearly five years on active duty and more than a year reserve time. The navy sent me to two diving schools in Washington, D.C.: second-class dive school, a ten-week diving and salvage school; and first-class dive school, which lasted seventeen-weeks. I graduated top in my class from both. In addition, I graduated fourth in my class from the navy's saturation dive school at Point Loma, California, which was about a fourteen-week program.

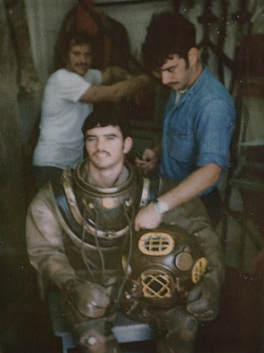

Control room, similar to the one on USS Elk River which we used for training.

Control room, similar to the one on USS Elk River which we used for training.

In 1975, there were 200 saturation divers in the navy, and basically, we either went to experimental diving stations or to special operations. I ended up in special ops on the fast-attack nuclear-powered submarine USS Halibut SSN-587, a 350-foot vessel with two levels in the middle section and a crew of 130 men, plus more than twenty divers.

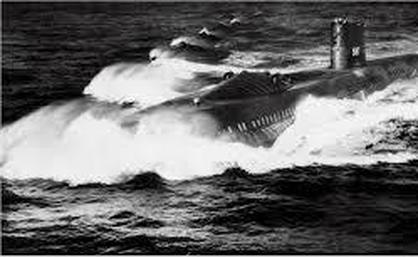

No other submarine had the unique silhouette of the USS Halibut (see picture and also drawing above). There was a huge metal bubble on the deck of our sub, named the “bat cave”; it was situated halfway between the bow of the sub and the conning tower. Then, on the tail end was something that looked like the Deep Submergence Rescue Vessel (DSRV). Once, when we were on the surface and coming into San Francisco Bay under the Golden Gate Bridge, a newscaster who was in a helicopter reported seeing our sub, and he described it as looking like it was pregnant (bat cave) and carrying a baby on its back (DSRV).

I loved the stealth, secrecy, and capabilities of submarines, from the red lights that glowed at night in the main control room (so that if we surfaced, we could see immediately without needing to adjust our eyes to the darkness), to the eighteen-hour days (we slept six hours, worked six hours, and studied six hours. Because it was all done underwater, one never knew if it was night or day except by looking at his watch.).

The following are a few of John Piña Craven’s quotes when speaking of our submarine: “The Halibut was responsible for the success of at least two of the most significant espionage missions of our time” (The Silent War, p. 140). There were many major technical difficulties for the overhaul of the Halibut to make it ready for these operations, however, he said, “But I think these problems pale beside the importance and ultimate impact of the intelligence operations that Halibut would be involved in and the grave dangers she would face” (p. 142), more on this further on.

At this time in the life of our sub, it had become a diving platform and existed to take us divers where we needed to go. We would make our dives and then return to port; our missions (unless training) would last from two to three months. In all, I was attached to the USS Halibut for a year and a half.

During this time, I was asked by an officer, who oversaw security for our mission, what I thought about the special operation. My response was then, and still is today, “Our enemies do similar things to us, and we would be irresponsible not to do the same.” While we were in port, the navy would send out teams to try to find out what we were doing, with the idea that if they could discover our mission, then our security was not good enough. A cover story was created to disguise the actual mission, and we were told to stay out of certain stores because of the possible connection with what we were doing.

In preparation for our special ops, we would make training dives in excess of 400 feet in depth, which lasted seven days. We stayed in a diving chamber during this period and were in the water for a few hours each day. To breathe air at such a depth would make one dangerously drunk (called nitrogen narcosis), so we breathed a special mix of helium and oxygen. The seven days were divided into three days at depth and four days of decompression.

Decompression is when the built-up helium in the bloodstream is given time to come out, so bubbles will not form in the diver’s blood. At 400 feet, the pressure on your body would be twelve times greater than on the surface. The inside of a submarine is kept at one atmosphere (what we have on the surface), so if a door is opened to the sea, such as a door on the bottom of a submarine, the seawater would immediately enter and flood the sub. But our diving chamber was kept at the same pressure as the outside water, in our case twelve times greater than on the surface (or twelve atmospheres), so when we opened a door on the bottom of our diving chamber, the water would not come in. But this extra pressure means divers would be breathing twelve times as much gas in one breath as they would on the surface. All this “extra” gas would be forced into a diver’s lungs and then into his bloodstream, which is why we decompressed—to give time for the gas to come out of our bloodstream.

It is called saturation diving because in a dive of more than twelve hours, the bloodstream becomes saturated with whatever gases (in our case, helium and oxygen) a diver breathes, and he cannot take any more into his bloodstream unless he goes deeper.

Once our boat (and it is proper to call a submarine either a boat or sub) arrived at our dive station, it was positioned in close proximity to where the dives needed to be made. Our sub had side thrusters on it and could actually go sideways at a couple of knots per hour.

These dives were manned from two control rooms. The small control room or “secondary control room”, run by the divers, looked like the inside of a space capsule, and I loved it! It seated two people and contained more than sixty valves, plus pressure gauges for the different gasses and depth gauges for the pressure inside the different compartments within the diving chamber. This cramped control room housed about two dozen small lights on the display console, which blinked if something went wrong. In addition, two TV monitors were squeezed into the space, as the navy monitored most everything we did on camera, both inside the diving chamber and outside in the water. We also used a round, self-propelled, two-foot-diameter TV camera with little thrusters that turned and moved about in the water, which we called the “swimming eyeball” or “eye”. This was controlled from the main control room, which was in the area of our sub’s periscopes, where the diving officer and master diver sat.

No other submarine had the unique silhouette of the USS Halibut (see picture and also drawing above). There was a huge metal bubble on the deck of our sub, named the “bat cave”; it was situated halfway between the bow of the sub and the conning tower. Then, on the tail end was something that looked like the Deep Submergence Rescue Vessel (DSRV). Once, when we were on the surface and coming into San Francisco Bay under the Golden Gate Bridge, a newscaster who was in a helicopter reported seeing our sub, and he described it as looking like it was pregnant (bat cave) and carrying a baby on its back (DSRV).

I loved the stealth, secrecy, and capabilities of submarines, from the red lights that glowed at night in the main control room (so that if we surfaced, we could see immediately without needing to adjust our eyes to the darkness), to the eighteen-hour days (we slept six hours, worked six hours, and studied six hours. Because it was all done underwater, one never knew if it was night or day except by looking at his watch.).

The following are a few of John Piña Craven’s quotes when speaking of our submarine: “The Halibut was responsible for the success of at least two of the most significant espionage missions of our time” (The Silent War, p. 140). There were many major technical difficulties for the overhaul of the Halibut to make it ready for these operations, however, he said, “But I think these problems pale beside the importance and ultimate impact of the intelligence operations that Halibut would be involved in and the grave dangers she would face” (p. 142), more on this further on.

At this time in the life of our sub, it had become a diving platform and existed to take us divers where we needed to go. We would make our dives and then return to port; our missions (unless training) would last from two to three months. In all, I was attached to the USS Halibut for a year and a half.

During this time, I was asked by an officer, who oversaw security for our mission, what I thought about the special operation. My response was then, and still is today, “Our enemies do similar things to us, and we would be irresponsible not to do the same.” While we were in port, the navy would send out teams to try to find out what we were doing, with the idea that if they could discover our mission, then our security was not good enough. A cover story was created to disguise the actual mission, and we were told to stay out of certain stores because of the possible connection with what we were doing.

In preparation for our special ops, we would make training dives in excess of 400 feet in depth, which lasted seven days. We stayed in a diving chamber during this period and were in the water for a few hours each day. To breathe air at such a depth would make one dangerously drunk (called nitrogen narcosis), so we breathed a special mix of helium and oxygen. The seven days were divided into three days at depth and four days of decompression.

Decompression is when the built-up helium in the bloodstream is given time to come out, so bubbles will not form in the diver’s blood. At 400 feet, the pressure on your body would be twelve times greater than on the surface. The inside of a submarine is kept at one atmosphere (what we have on the surface), so if a door is opened to the sea, such as a door on the bottom of a submarine, the seawater would immediately enter and flood the sub. But our diving chamber was kept at the same pressure as the outside water, in our case twelve times greater than on the surface (or twelve atmospheres), so when we opened a door on the bottom of our diving chamber, the water would not come in. But this extra pressure means divers would be breathing twelve times as much gas in one breath as they would on the surface. All this “extra” gas would be forced into a diver’s lungs and then into his bloodstream, which is why we decompressed—to give time for the gas to come out of our bloodstream.

It is called saturation diving because in a dive of more than twelve hours, the bloodstream becomes saturated with whatever gases (in our case, helium and oxygen) a diver breathes, and he cannot take any more into his bloodstream unless he goes deeper.

Once our boat (and it is proper to call a submarine either a boat or sub) arrived at our dive station, it was positioned in close proximity to where the dives needed to be made. Our sub had side thrusters on it and could actually go sideways at a couple of knots per hour.

These dives were manned from two control rooms. The small control room or “secondary control room”, run by the divers, looked like the inside of a space capsule, and I loved it! It seated two people and contained more than sixty valves, plus pressure gauges for the different gasses and depth gauges for the pressure inside the different compartments within the diving chamber. This cramped control room housed about two dozen small lights on the display console, which blinked if something went wrong. In addition, two TV monitors were squeezed into the space, as the navy monitored most everything we did on camera, both inside the diving chamber and outside in the water. We also used a round, self-propelled, two-foot-diameter TV camera with little thrusters that turned and moved about in the water, which we called the “swimming eyeball” or “eye”. This was controlled from the main control room, which was in the area of our sub’s periscopes, where the diving officer and master diver sat.

|

USS Elk River with valves outside of dive

chamber to the right. Though cramped it was spacious compared to our Sub. |

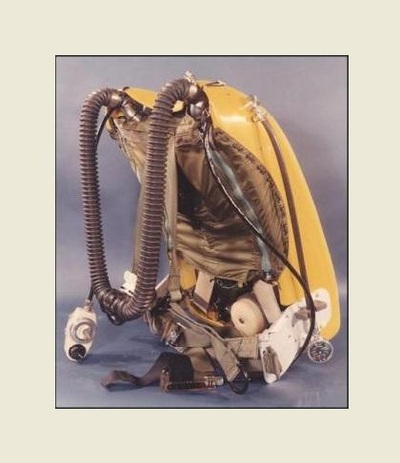

The diving rigs were Westinghouse

"Abalone" or Mk 11. The rumored price was 3 million for 6 rigs! |

The diving chamber, from which the dives were made, was situated directly next to the secondary control room and had space for four divers. We slept, ate, took sponge baths, and made our dives from this small, three-room, tube-shaped diving chamber, which we were not able to completely stand up in because the ceiling was too low. One room was for “pressing down” more divers or a medical officer in the event of an emergency, a second was for sleeping and housed a toilet and sink, and the third was the lockout chamber, where divers prepared to enter the water. Each room or compartment of the chamber was separated by round metal doors more than an inch-thick, which could withstand the extreme pressures at that depth. In addition, there was also a small, two-foot-by-one-foot chamber to convey food back and forth to the divers.

Owing to the necessity of breathing helium and oxygen in place of nitrogen and oxygen (air), we used a special communication system that unscrambled our speech so we would not sound like Donald Duck, an effect brought on by the helium on our vocal cords. Attached to each diver were five hoses or cables 350 feet long: the hot-water cable, a wire cable to pull us back in the event of an emergency, a communication cable, and one hose that pushed our gas to us, and one that pulled it back so no bubbles would reach the surface and no one would know we were there.

One may be thinking that, because of the cables connected to me I was not able to swim around freely, like scuba diving. That’s true, but I didn’t want to. The depths were too deep for scuba diving. At that depth, when a diver has his bloodstream saturated with the gas he is breathing, if he swam only halfway to the surface, he would die.

The sea held little scenery at 400 feet, only some giant king crabs and strange-looking fish about eighteen inches long, with heads almost half the size of their bodies and eyeballs bigger than a human's. They were not afraid of us divers and swam right up to us and stared. They even sat in the silt at the sea bottom, still gazing at us, which seemed eerie.

We dove between “windows” in the tides to prevent fighting the currents and for better visibility, which in the frigid blackness was only about six feet. The sea’s temperature was 27 degrees Fahrenheit and would have been frozen solid had it not been saltwater. Because of this us divers wore two wet suits, one eighth-inch-thin rubber suit and one three-eighths-inch thick, with hot water pumped between the two to prevent hypothermia. We needed the eighth-inch liner so the 140-degree water would not scald us. Before a dive, I put my hand into the seawater just to see how cold it felt, and I could not hold my hand in it. The saltwater tried to freeze the blood in my hand, and I could feel it go up my arm and into my heart!

On one dive, some gas leaked under my face mask, which was attached to the liner. The gas seeped over my head and got trapped under the liner, causing my face mask to rise up on my face. On my second dive, I didn’t want to fight with my face mask again, so I had this “bright” idea to cut two small holes in the thin liner, so any bubbles could go through it and not cause my mask to rise up. The problem was, I didn’t realize it would take time for the hot water to circulate up that high in my wet suit, so when I entered the sea, in came the freezing cold water straight to my head. It felt like someone was driving two spikes into my brain! I wasn’t sure what to do, and when those in control kept asking through our communication system why I was not moving out, I stalled for time. A diver just didn’t bail out and crawl back in the dive chamber; he might not be allowed to make the dive and another diver could take his place. Fortunately, after a few minutes and a terrible headache, the hot water circulated up to my head, and I was able to perform the dive.

Owing to the necessity of breathing helium and oxygen in place of nitrogen and oxygen (air), we used a special communication system that unscrambled our speech so we would not sound like Donald Duck, an effect brought on by the helium on our vocal cords. Attached to each diver were five hoses or cables 350 feet long: the hot-water cable, a wire cable to pull us back in the event of an emergency, a communication cable, and one hose that pushed our gas to us, and one that pulled it back so no bubbles would reach the surface and no one would know we were there.

One may be thinking that, because of the cables connected to me I was not able to swim around freely, like scuba diving. That’s true, but I didn’t want to. The depths were too deep for scuba diving. At that depth, when a diver has his bloodstream saturated with the gas he is breathing, if he swam only halfway to the surface, he would die.

The sea held little scenery at 400 feet, only some giant king crabs and strange-looking fish about eighteen inches long, with heads almost half the size of their bodies and eyeballs bigger than a human's. They were not afraid of us divers and swam right up to us and stared. They even sat in the silt at the sea bottom, still gazing at us, which seemed eerie.

We dove between “windows” in the tides to prevent fighting the currents and for better visibility, which in the frigid blackness was only about six feet. The sea’s temperature was 27 degrees Fahrenheit and would have been frozen solid had it not been saltwater. Because of this us divers wore two wet suits, one eighth-inch-thin rubber suit and one three-eighths-inch thick, with hot water pumped between the two to prevent hypothermia. We needed the eighth-inch liner so the 140-degree water would not scald us. Before a dive, I put my hand into the seawater just to see how cold it felt, and I could not hold my hand in it. The saltwater tried to freeze the blood in my hand, and I could feel it go up my arm and into my heart!

On one dive, some gas leaked under my face mask, which was attached to the liner. The gas seeped over my head and got trapped under the liner, causing my face mask to rise up on my face. On my second dive, I didn’t want to fight with my face mask again, so I had this “bright” idea to cut two small holes in the thin liner, so any bubbles could go through it and not cause my mask to rise up. The problem was, I didn’t realize it would take time for the hot water to circulate up that high in my wet suit, so when I entered the sea, in came the freezing cold water straight to my head. It felt like someone was driving two spikes into my brain! I wasn’t sure what to do, and when those in control kept asking through our communication system why I was not moving out, I stalled for time. A diver just didn’t bail out and crawl back in the dive chamber; he might not be allowed to make the dive and another diver could take his place. Fortunately, after a few minutes and a terrible headache, the hot water circulated up to my head, and I was able to perform the dive.

Our Westinghouse diving rigs were semi-rebreathers. We rebreathed our mixed gas, only one in six breaths was a fresh supply of oxygen and helium. Our dive rig would scrub the carbon dioxide that we exhaled, and the fresh gas mix was supplied by our hoses. Our semi-rebreather also heated the mixed gas we breathed, as the freezing water made the mixed gas so cold, it would give you a headache. Our face mask was doubled sealed, one seal around our face and one around our mouth and nose, so if our face mask flooded, we could still breathe. There was also a head set and speaker inside our mask for communications and a red light that came on in the event our gas mix was somehow blocked. This red light was triggered by the use of an emergency tank with a ten-minute supply of gas so we could get back to our dive chamber.

LEGION OF MERIT

LEGION OF MERIT

We wanted to make the dives.

I gave this technical part just to get to this point. There were twenty-one saturation divers on the sub, but only eight divers would make the two saturation dives necessary for this operation. The others would man the two control-rooms, which would run nonstop during the dives. More than eight of us wanted to make these dives, and those in charge would not tell us who would dive until we were two weeks out to sea. We had practiced a year for this one special operation, and I definitely wanted to be one of the eight chosen. My desire to make the dive had become so strong and important to me that I began to base all my decisions around it.

The reason this operation was so important to me was because it was important! All the divers knew that those who would make the dive would be put in for one of the highest medals our nation gives: The Legion of Merit.

We were bound by secrecy, and most of the submariners on our sub did not even know where our sub had gone, let alone what we were doing. But the Legion of Merit would be a witness that we had participated in something of great value to America. In short, it would make me feel like I had done something more than practice. I accept that, for some people, a medal was not necessary or important, but it was to me.

I gave this technical part just to get to this point. There were twenty-one saturation divers on the sub, but only eight divers would make the two saturation dives necessary for this operation. The others would man the two control-rooms, which would run nonstop during the dives. More than eight of us wanted to make these dives, and those in charge would not tell us who would dive until we were two weeks out to sea. We had practiced a year for this one special operation, and I definitely wanted to be one of the eight chosen. My desire to make the dive had become so strong and important to me that I began to base all my decisions around it.

The reason this operation was so important to me was because it was important! All the divers knew that those who would make the dive would be put in for one of the highest medals our nation gives: The Legion of Merit.

We were bound by secrecy, and most of the submariners on our sub did not even know where our sub had gone, let alone what we were doing. But the Legion of Merit would be a witness that we had participated in something of great value to America. In short, it would make me feel like I had done something more than practice. I accept that, for some people, a medal was not necessary or important, but it was to me.

The USS Halibut was equipped with "skids" so she could sit on the ocean floor.

The operation, which continued after I left the navy in 1975, remained safe until the 1980s, when it was compromised by National Security Agency (NSA) cryptologist Ronald W. Pelton. Pelton was tried and convicted of espionage and sentenced to three concurrent life sentences at the federal correction institution, of Allenwood, Pennsylvania.

In his book The Silent War, John Craven said, “The KGB succeeded in recruiting … [Ronald W. Pelton, who] … would betray how the Navy had tapped Soviet underwater communications cables, including the crucial role of saturation diving in those operations” (p. 278–279).

God Was Working

While on the submarine, I wrestled with whether or not I would serve God. There was a Bible study on the sub that I had been to a few times, and to be honest, I was a little concerned about others seeing me go to it. I thought if I attended the meetings, others would poke fun at me, and more importantly (though I now know unfounded), I had this thought I might not be chosen for the dive. There were at least three officers who would take part in the decision process, and any one of them could stop a diver from making the dive. I can see now I was too concerned about what other people thought.

Happily, God had His faithful witnesses on our sub, who were more concerned about the Lord. I had trusted Christ a few months prior to being assigned to the sub, and on the Halibut I met I a man who I will call “Chief”. He explained a lot about God and His Word, and I always had questions for him. One day, while I was asking him a question, he said,

“Garry, you ought to go to Bible college.”

“Yeah, right, Chief,” I replied, laughing.

I had no intention of going to any college, let alone Bible college, but after he said that, I never quite got the idea out of my head. And God used him greatly to encourage me in my Christian life. God had also placed another Christian brother on this submarine, who I will call “Preacher.” He led a Bible study, and on Sunday he preached. I had never heard preaching before in my life. It wasn’t some sermonizing from a denominational textbook, but standing up and declaring God’s Word, and it stirred my heart.

Though teaching the Bible is also of our Lord, God chooses preaching as one of His main ways to grab hold of people (I Corinthians 1:21). Teaching is giving out information but preaching has urgency in it. The purpose of preaching is to bring change, not to fill you with information.

As I said before, I was afraid I might not make the dive if I was seen going with the “God squad” (as the Christians were called) to the Bible studies. One time when on my way to a Bible study, a couple of submariners stopped me and wanted to talk. But I was in a hurry and was trying to figure out some way to leave without them asking where I was going. But they kept on talking without giving me a chance to speak. I finally caught on that they were doing it intentionally because they had figured out where I was going. This was before all the electronic games and there is not much recreation on a submarine, and finding someone to poke fun at becomes a favorite pastime.

“I’ve got to go,” I finally said.

“Well don’t be late for your prayer time.” They got a laugh out of it.

“Yeah, and I will pray for you!” I responded. And I pulled out my Bible that I had hid in

my pocket and went to the Bible study.

Struggling with a decision.

To me, making this dive was a dream come true. I remember praying, “Lord, please let me make this dive.” I told the Lord I would start going to the Bible study regularly after the dive and live a better life for Him. But I kept getting this feeling the Lord only wanted to know one thing: “What if I don’t let you make this dive?” I told the Lord, “I really want to make this dive. It’s very important to me.” And again, I had the same impression, but only stronger, that the Lord was saying to me, “What if I don’t let you?”

“Lord,” I pleaded, “please let me. It’s really important to me.” But I could not shake the thought out of my head, “If I don’t let you, will you still serve me anyway?” It seemed like a bitter cup to drink. I felt heartsick, thinking about being passed over and someone else taking my place. And the only thing I thought the Lord wanted to know was, “What if I don’t let you?” There is only one response the Lord wants in a situation like this: do what He wants, even if you don't get what you want. I said, “Okay, Lord, I will serve you even if you don’t let me make the dive,” and then I added, “but I really would like to do this.” The Lord likes it when you put the decision in His hands, where it needs to be.

The next day, the diving officer walked up to me and said, “You're making the first dive,” and then he walked off. I was thankful to the Lord, and I thought that since I had planned to go to the Bible study after the dive, why not start before it, which I did.

The Dives

As I said before, these particular dives lasted seven days, but we were actually only in the water three times on the first saturation dive. Each wet dive (actually in the water) was carried out with two divers in the water, about two hours at a time. I accomplished the first water entry and served as lead diver on the third one.

After the submarine returned to port, I fulfilled my last month of active duty and was discharged from the navy, and then I registered for Bible college.

The Navy awarded me the Legion of Merit for this dive, along with all the divers who got in the water. The commendation I received reads as follows: “SW2 [DV] Garry M. Matheny, USN. Deployed for a second and even more arduous deployment. During this 96-day deployment he participated in a submarine operation of great importance to the government of the United States. Although description of this operation is precluded by security constraints, the ratee performed in a hostile environment under great operational stress requiring exceptional courage, constant vigilance and keen professional competence. His performance in that environment was superb and was a key factor in the ship’s success in that operation.”

It was signed by C. R. Larson, Capt. USN Commanding Officer. (Captain Charles R. Larson later became a four-star admiral and was given command of the entire Pacific. Born November 20, 1936—Died July 26, 2014.)

Farewell to a great submarine, the USS Halibut.

She was decommissioned at Mare Island California in June of 1976.

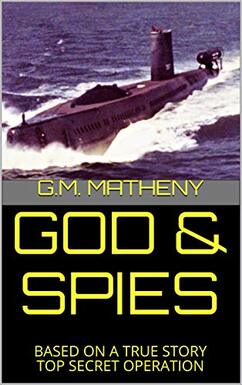

(Since writing this our operation has been declassified and I published GOD & SPIES: BASED ON A TRUE STORY, TOP SECRET OPERATION by G.M. Matheny. Both Kindle and paperback, 250 pages. See below.)

In his book The Silent War, John Craven said, “The KGB succeeded in recruiting … [Ronald W. Pelton, who] … would betray how the Navy had tapped Soviet underwater communications cables, including the crucial role of saturation diving in those operations” (p. 278–279).

God Was Working

While on the submarine, I wrestled with whether or not I would serve God. There was a Bible study on the sub that I had been to a few times, and to be honest, I was a little concerned about others seeing me go to it. I thought if I attended the meetings, others would poke fun at me, and more importantly (though I now know unfounded), I had this thought I might not be chosen for the dive. There were at least three officers who would take part in the decision process, and any one of them could stop a diver from making the dive. I can see now I was too concerned about what other people thought.

Happily, God had His faithful witnesses on our sub, who were more concerned about the Lord. I had trusted Christ a few months prior to being assigned to the sub, and on the Halibut I met I a man who I will call “Chief”. He explained a lot about God and His Word, and I always had questions for him. One day, while I was asking him a question, he said,

“Garry, you ought to go to Bible college.”

“Yeah, right, Chief,” I replied, laughing.

I had no intention of going to any college, let alone Bible college, but after he said that, I never quite got the idea out of my head. And God used him greatly to encourage me in my Christian life. God had also placed another Christian brother on this submarine, who I will call “Preacher.” He led a Bible study, and on Sunday he preached. I had never heard preaching before in my life. It wasn’t some sermonizing from a denominational textbook, but standing up and declaring God’s Word, and it stirred my heart.

Though teaching the Bible is also of our Lord, God chooses preaching as one of His main ways to grab hold of people (I Corinthians 1:21). Teaching is giving out information but preaching has urgency in it. The purpose of preaching is to bring change, not to fill you with information.

As I said before, I was afraid I might not make the dive if I was seen going with the “God squad” (as the Christians were called) to the Bible studies. One time when on my way to a Bible study, a couple of submariners stopped me and wanted to talk. But I was in a hurry and was trying to figure out some way to leave without them asking where I was going. But they kept on talking without giving me a chance to speak. I finally caught on that they were doing it intentionally because they had figured out where I was going. This was before all the electronic games and there is not much recreation on a submarine, and finding someone to poke fun at becomes a favorite pastime.

“I’ve got to go,” I finally said.

“Well don’t be late for your prayer time.” They got a laugh out of it.

“Yeah, and I will pray for you!” I responded. And I pulled out my Bible that I had hid in

my pocket and went to the Bible study.

Struggling with a decision.

To me, making this dive was a dream come true. I remember praying, “Lord, please let me make this dive.” I told the Lord I would start going to the Bible study regularly after the dive and live a better life for Him. But I kept getting this feeling the Lord only wanted to know one thing: “What if I don’t let you make this dive?” I told the Lord, “I really want to make this dive. It’s very important to me.” And again, I had the same impression, but only stronger, that the Lord was saying to me, “What if I don’t let you?”

“Lord,” I pleaded, “please let me. It’s really important to me.” But I could not shake the thought out of my head, “If I don’t let you, will you still serve me anyway?” It seemed like a bitter cup to drink. I felt heartsick, thinking about being passed over and someone else taking my place. And the only thing I thought the Lord wanted to know was, “What if I don’t let you?” There is only one response the Lord wants in a situation like this: do what He wants, even if you don't get what you want. I said, “Okay, Lord, I will serve you even if you don’t let me make the dive,” and then I added, “but I really would like to do this.” The Lord likes it when you put the decision in His hands, where it needs to be.

The next day, the diving officer walked up to me and said, “You're making the first dive,” and then he walked off. I was thankful to the Lord, and I thought that since I had planned to go to the Bible study after the dive, why not start before it, which I did.

The Dives

As I said before, these particular dives lasted seven days, but we were actually only in the water three times on the first saturation dive. Each wet dive (actually in the water) was carried out with two divers in the water, about two hours at a time. I accomplished the first water entry and served as lead diver on the third one.

After the submarine returned to port, I fulfilled my last month of active duty and was discharged from the navy, and then I registered for Bible college.

The Navy awarded me the Legion of Merit for this dive, along with all the divers who got in the water. The commendation I received reads as follows: “SW2 [DV] Garry M. Matheny, USN. Deployed for a second and even more arduous deployment. During this 96-day deployment he participated in a submarine operation of great importance to the government of the United States. Although description of this operation is precluded by security constraints, the ratee performed in a hostile environment under great operational stress requiring exceptional courage, constant vigilance and keen professional competence. His performance in that environment was superb and was a key factor in the ship’s success in that operation.”

It was signed by C. R. Larson, Capt. USN Commanding Officer. (Captain Charles R. Larson later became a four-star admiral and was given command of the entire Pacific. Born November 20, 1936—Died July 26, 2014.)

Farewell to a great submarine, the USS Halibut.

She was decommissioned at Mare Island California in June of 1976.

(Since writing this our operation has been declassified and I published GOD & SPIES: BASED ON A TRUE STORY, TOP SECRET OPERATION by G.M. Matheny. Both Kindle and paperback, 250 pages. See below.)

Operation Ivy Bells, true story of submarine espionage.

(32 min)

GOD & SPIES

We have it on Amazon if one wants a paper back but it can be read for free at the top of the page where it says "Free eBooks"

NOW DECLASSIFIED TOP SECRET OPERATION

GM Matheny was a US Navy saturation diver on the nuclear submarine USS Halibut. Involved in "Operation Ivy Bells". America’s most important and most dangerous of the Cold War clandestine operations. If you like good old fashioned American bravado, espionage and American history, you will enjoy this book.

Based on A True Story - The Mount Everest of Spy Missions

Firsthand account of history's greatest intelligence coup. Operation Ivy Bells was not a onetime intercept of foreign intelligence, but an ongoing operation of multiple Soviet military channels, twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, which lasted for years! Another reason for the high interest in our operation was the audacious nature in which it was done—with not one person risking his neck but a whole crew of a nuclear submarine.

How did I end up as a navy diver, four hundred feet down in a frigid Russian sea? After making my dad totally disgusted with me, I set out to make him happy. “Honour thy father” - I struggled with a decision to serve God. “Lord, I will give my life to you and serve you if you let me make this dive.” But I had the impression He only wanted to know one thing: “What if I do not let you? Will you serve me anyway?”

BOOK EXCERPT "The tenders in the dive chamber who are bringing in Red Diver’s umbilical cable, unexpectedly have his cable ripped out of their hands! One of the tenders says, “What’s going on?” Matheny’s fins have landed back onto the first leg of the DSRV, which keeps him from sliding back any farther. He then pulls toward him about 30 feet of his umbilical cord and makes a dash for the next leg coming down from the DSRV. He makes it, but the red light shining in Matheny’s face is reminding him he is running out of time. From his position, he can see the light shining down in the water from the entry point back into the dive chamber. He positions himself to push off the last leg of the DSRV so he can enter the dive chamber. Then unexplainably he is again jerked backward with another sharp pull! This time his face mask slams into the leg of the DSRV. Matheny hurriedly makes a grab for this leg clinging to it."

Paperback 273 pages, $12.90 https://www.amazon.com/dp/1075452430

Kindle $6.30 https://www.amazon.com/dp/B07TCSLFWR

GOD & SPIES

We have it on Amazon if one wants a paper back but it can be read for free at the top of the page where it says "Free eBooks"

NOW DECLASSIFIED TOP SECRET OPERATION

GM Matheny was a US Navy saturation diver on the nuclear submarine USS Halibut. Involved in "Operation Ivy Bells". America’s most important and most dangerous of the Cold War clandestine operations. If you like good old fashioned American bravado, espionage and American history, you will enjoy this book.

Based on A True Story - The Mount Everest of Spy Missions

Firsthand account of history's greatest intelligence coup. Operation Ivy Bells was not a onetime intercept of foreign intelligence, but an ongoing operation of multiple Soviet military channels, twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, which lasted for years! Another reason for the high interest in our operation was the audacious nature in which it was done—with not one person risking his neck but a whole crew of a nuclear submarine.

How did I end up as a navy diver, four hundred feet down in a frigid Russian sea? After making my dad totally disgusted with me, I set out to make him happy. “Honour thy father” - I struggled with a decision to serve God. “Lord, I will give my life to you and serve you if you let me make this dive.” But I had the impression He only wanted to know one thing: “What if I do not let you? Will you serve me anyway?”

BOOK EXCERPT "The tenders in the dive chamber who are bringing in Red Diver’s umbilical cable, unexpectedly have his cable ripped out of their hands! One of the tenders says, “What’s going on?” Matheny’s fins have landed back onto the first leg of the DSRV, which keeps him from sliding back any farther. He then pulls toward him about 30 feet of his umbilical cord and makes a dash for the next leg coming down from the DSRV. He makes it, but the red light shining in Matheny’s face is reminding him he is running out of time. From his position, he can see the light shining down in the water from the entry point back into the dive chamber. He positions himself to push off the last leg of the DSRV so he can enter the dive chamber. Then unexplainably he is again jerked backward with another sharp pull! This time his face mask slams into the leg of the DSRV. Matheny hurriedly makes a grab for this leg clinging to it."

Paperback 273 pages, $12.90 https://www.amazon.com/dp/1075452430

Kindle $6.30 https://www.amazon.com/dp/B07TCSLFWR

What others are saying.

Pastor Marvin McKenzie (February 7, 2018)

“Garry Matheny is a friend and a fellow preacher. Prior to his salvation he served in the Navy as an elite saturation diver. He was involved in one of America’s most important (and dangerous) clandestine operations."

"Garry does a marvelous job of weaving recently declassified information regarding the operation, the record of an intelligence analyst spending the rest of his life in prison for selling the details of this operation to the Russians and his own eyewitness account of the operation itself."

"If you like good old fashioned American bravado, espionage and American history, you will enjoy this book.”

David Meyer (February 26, 2018)

“I could not stop reading once I started. This book is for anyone that likes stories about submarines, divers, spies and or scripture. It’s all there in this interesting book.”

Paperback 223 pages, $12.50 https://www.amazon.com/GOD-SPIES-RECENTLY-DECLASSIFIED-OPERATION/dp/1977079342/ref=tmm_pap_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=&sr

Kindle $7.75 https://www.amazon.com/GOD-SPIES-RECENTLY-DECLASSIFIED-OPERATION-ebook/dp/B079K4BNMX/ref=tmm_kin_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=&sr=

Pastor Marvin McKenzie (February 7, 2018)

“Garry Matheny is a friend and a fellow preacher. Prior to his salvation he served in the Navy as an elite saturation diver. He was involved in one of America’s most important (and dangerous) clandestine operations."

"Garry does a marvelous job of weaving recently declassified information regarding the operation, the record of an intelligence analyst spending the rest of his life in prison for selling the details of this operation to the Russians and his own eyewitness account of the operation itself."

"If you like good old fashioned American bravado, espionage and American history, you will enjoy this book.”

David Meyer (February 26, 2018)

“I could not stop reading once I started. This book is for anyone that likes stories about submarines, divers, spies and or scripture. It’s all there in this interesting book.”

Paperback 223 pages, $12.50 https://www.amazon.com/GOD-SPIES-RECENTLY-DECLASSIFIED-OPERATION/dp/1977079342/ref=tmm_pap_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=&sr

Kindle $7.75 https://www.amazon.com/GOD-SPIES-RECENTLY-DECLASSIFIED-OPERATION-ebook/dp/B079K4BNMX/ref=tmm_kin_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=&sr=