Why Tahpanhes is not Tel Defeneh

also named Tell Defenneh, Daphnae, Daphnai,

and which city is.

(I have not had time to fix the typos.)

The following is taken from our book THE QUEST FOR THE GREAT STONES OF THE PHOPHET JEREMIAH (Found under the section "FREE BOOKS") which was not in a scholarly format but a first person account of our search for the “great stones” of Jeremiah 43:9-10. But I have here taken out the story line and left “just the facts.” Bible quotations are taken from The King James Bible (KJV). All quotations, whether from the Bible, historians, archaeologists, or Bible scholars, are italicized. Bold print or underlining used in verses or quotations of others reflects my emphasis. For the meaning of the Bible words in the original languages, I have used Gesenius’s Lexicon and Strong’s Concordance (hereafter labeled Strong’s) with Hebrew and Greek Lexicon, which is on line. Sorry about the numbers for the footnotes, I was not able to get the subscript or superscript to work on this web site. The footnote numbers7 will appear the same size as the letters.

also named Tell Defenneh, Daphnae, Daphnai,

and which city is.

(I have not had time to fix the typos.)

The following is taken from our book THE QUEST FOR THE GREAT STONES OF THE PHOPHET JEREMIAH (Found under the section "FREE BOOKS") which was not in a scholarly format but a first person account of our search for the “great stones” of Jeremiah 43:9-10. But I have here taken out the story line and left “just the facts.” Bible quotations are taken from The King James Bible (KJV). All quotations, whether from the Bible, historians, archaeologists, or Bible scholars, are italicized. Bold print or underlining used in verses or quotations of others reflects my emphasis. For the meaning of the Bible words in the original languages, I have used Gesenius’s Lexicon and Strong’s Concordance (hereafter labeled Strong’s) with Hebrew and Greek Lexicon, which is on line. Sorry about the numbers for the footnotes, I was not able to get the subscript or superscript to work on this web site. The footnote numbers7 will appear the same size as the letters.

“Take great stones in thine hand, and hide them in the clay in the brickkiln, which is at the entry of Pharaoh's house in Tahpanhes, in the sight of the men of Judah; And say unto them, Thus saith the LORD of hosts, the God of Israel; Behold, I will send and take Nebuchadrezzar the king of Babylon, my servant, and will set his throne upon these stones that I have hid; and he shall spread his royal pavilion over them.” (Jeremiah 43:9-10)

In 1886 British archaeologist Sir Flinders Petrie, also known as “the father of modern archaeology,” excavated the site of Tell Defenneh. The archaeological site of Tell Defenneh is believed to be the biblical city of Tahpanhes in Jeremiah 43:9, also spelled “Tahapanes” in Jeremiah 2:16, and “Tehaphnehes” in Ezekiel 30:18.

In 1886 British archaeologist Sir Flinders Petrie, also known as “the father of modern archaeology,” excavated the site of Tell Defenneh. The archaeological site of Tell Defenneh is believed to be the biblical city of Tahpanhes in Jeremiah 43:9, also spelled “Tahapanes” in Jeremiah 2:16, and “Tehaphnehes” in Ezekiel 30:18.

My son Caleb (pictured above) and I went to Tell Defenneh/Daphnai in July 2005. The site had mud bricks, a few pieces of broken clay pots, lots of sand and a couple of signs that marked the spot but no tourists or signs of any being there.

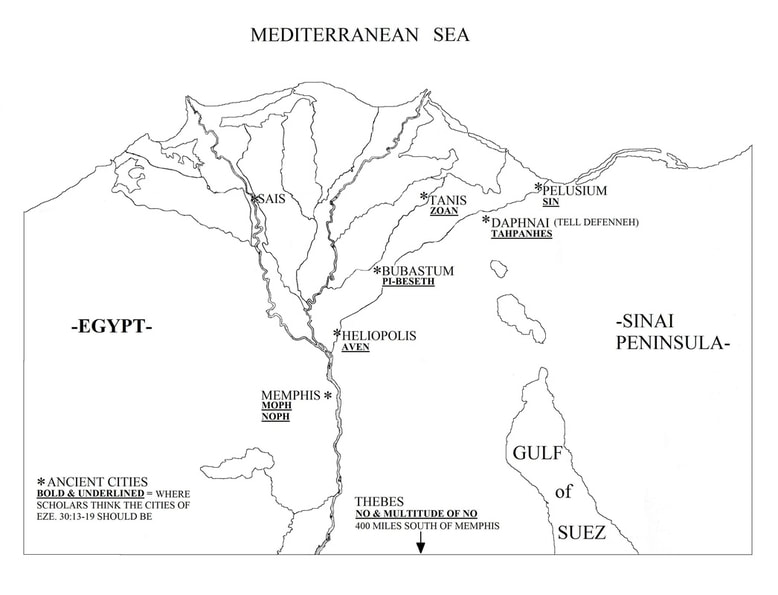

It will be helpful here to give a more complete description of Tell Defenneh, which is the Arabic name for the town of Daphnai. Tell Defenneh is in northern Egypt on the eastern side of the Nile Delta (see map) and served as a frontier fort. Pharaoh Psamtik I of the 26th Dynasty built it to house his Greek soldiers (mercenaries) he had employed to guard the road to Syria. This fort was connected to the Nile River by a canal that came right by it and no doubt received its supplies this way. Tell Defenneh came in contact with other groups of people by being on the caravan route to Israel and Syria but, according to Mr. Petrie, the bulk of the population was Greek, “At Defenneh, the bulk of the population seems to have been Greek; Greek pottery abounds….”1 Greek soldiers were stationed there from the founding of the fort in 664 B.C., and remained there until the time of Pharaoh Amases in the year 564 B.C., exactly one hundred years later.2 Jeremiah and the group with him were believed to have gone there shortly after the fall of Jerusalem in 586 B.C.. That would have been during the time the Greek soldiers were there or some 80 years after the fort’s founding and only twenty years before the Greek soldiers were removed.

I am not an archaeologist, so who am I to disagree with “the father of modern archaeology”? I had respect for Flinders Petrie, and still do, but I needed to look past this because Tell Defenneh had been excavated and Mr. Petrie made a search for the “great stones” of Jeremiah 43:9-10, but he had come up empty-handed. It was not adding up.

Reasons given by Mr. Petrie3 for why he believed Tell Defenneh was Tahpanhes of the Bible. I thought there were several reasons for Tell Defenneh being Tahpanhes of the Bible, but this was mainly because everything I read about it said it was. All archaeologists agree on this, including modern Bible scholars. They use the names of Tahpanhes and Tell Defenneh or Daphnai interchangeably, which caused me problems. Bible scholars would say or quote someone else as saying that Jeremiah came to the city of Daphnai, or tell you some ancient book places Tahpanhes at this site. I would then search for the article online or order the book only to find out that the book does not even mention Tahpanhes. And they felt justified in doing this because, in their minds, these towns were one and the same place.

First the “brickkiln” of Jeremiah 43:9, where the prophet Jeremiah buried the “great stones” outside of Pharaoh’s palace. And Mr. Petrie did find a raised brickwork or pavement in front of Pharaoh’s house. It was about three feet high by 100 feet long and 70 feet wide and it was sitting on sand. Sometimes he would refer to it as a “mastaba”, a name the Egyptians called it - an open air platform where a caravan might come and sell or unload their goods and transact business. The word that is translated brickkiln, in the Hebrew is “brickkiln or brickwork”,4 something that has been made out of bricks. And because this bricked platform was sitting out front of Pharaoh’s fort, he thought this would fit with the Bible account of Jeremiah at the city of Tahpanhes. But if the brickkiln or brickwork was the mastaba, which has not been proven, it certainly was not rare enough in itself to make it an identification for the town of Tahpanhes. Bricked areas have been found out front of other palaces in Egypt; I will say more about this later. Flinders Petrie himself said that even in his time these brick platforms were common “such as is now seen outside all great houses, and most small ones, in this country”.5

Mr. Petrie was sure that these Jews would have settled here at Tell Defenneh and were not likely to have gone further into Egypt. He said, “Such refugees would necessarily reach the frontier fort on the caravan road and would there find a mixed and mainly foreign population, Greek, Phoenician, and Egyptian, among whom their presence would not be resented, as it would by the still strictly protectionist Egyptians further in the country. That they would largely, or perhaps mainly, settle there [Tell Defenneh] would be the most natural course; they would be tolerated, they would find a constant communication with their own countrymen, and they would be as near to Judea as they could in safety remain, while they awaited a chance of returning”.8 But the scriptures teach otherwise, “The word that came to Jeremiah concerning all the Jews which dwell in the land of Egypt, which dwell at Migdol, and at Tahpanhes, and at Noph, and in the country of Pathros”.9 The location of Migdol is still disputed but everyone says that Noph is Memphis, in the heart of the country.

But his main reason for believing it was the biblical city of Tahpanhes was the name the Bedouins gave this site. I will quote from Mr. Petrie, “There is the remarkable name of the fort, ‘The palace of the Jew’s daughter,’ no such name is known anywhere else in the whole of Egypt. This is the one town in Egypt to which the ‘king’s daughters’ of Judah came”.6 These daughters of the king that he is referring to are found in Jeremiah 43:6, where those Jews who fled to Tahpanhes brought with them “the king’s daughters....” These daughters of the king are believed to be the daughters of the last king of Judah, King Zedekiah. King Zedekiah had been taken prisoner by King Nebuchadnezzar and forced to watch while his sons were executed, and then he was led off to Babylon. But his daughters ended up with the group that fled down to Egypt along with the prophet Jeremiah. And these daughters (more later) of the king did come to Tahpanhes. But the question is, where was Tahpanhes?

The name Tahpanhes in hieroglyphics has never been found on monuments in Egypt or in any of their writings. And there are those before Mr. Petrie who disagreed, believing Tahpanhes to be one of other possible sites.7 And though I would not agree on their locations, I wanted to show that there was not an agreement on the site of Tahpanhes before Mr. Petrie.

Why did not Jeremiah call this town Daphnai, if he indeed was there? Nor does the Greek historian Herodotus, who wrote in 440 B.C., ever call it Tahpanhes, but only Daphnai. Pharaoh Psamtik I (664 – 610 BC) who built this fort, would have given his frontier fort an Egyptian name whatever it was, but the site name Daphnai, which is a Greek name, was, in all probability, from the Greek soldiers themselves, and it therefore would have had its name Daphnai at the time Jeremiah was supposed to have been there. But he never calls it this.

As to the origin of the name Daphnai, some say it was a poor attempt by the Greek soldiers to pronounce the Egyptian name Tahpanhes. The truth is, this was a common name for the Greek soldiers who inhabited this site and most likely gave it its Greek name Daphnai (also spelled Daphnae). The name Daphne in Greek means “laurel” and was also the name of a well known Greek mythological character, Daphne, and there were ancient cities both in Greece and Syria with this name (Daphnes, Daphne).

Why could not Mr. Petrie find the “great stones”? If he was in the right town he should have found them. He did find small objects such as arrowheads in this platform and even believed that other small objects could have been found before him saying, “That they should be now found after having been buried, is just explained by the denuded [eroded] state of the platform.” The “they” he was referring to were smaller objects that would have been exposed by the erosion of the platform. But he also said, “Unhappily, the great denudation which has gone on has swept away most of this platform, and we could not expect to find the stones whose hiding is described by Jeremiah”.10 But stones would not have eroded, especially if they were large stones, and where would they have been swept away? Except for the mounds of the site, the place is flat in all four directions. Yet he uses this same argument of the “denuded state of the platform”, as a reason why smaller objects could have been found out in the open, and then turns around and uses it again for a reason why bigger objects would not have been found.

“The palace of the Jew’s daughter,” you can scarcely find an article on Defenneh or Tahpanhes that will not use this to confirm the location of the biblical city of Tahpanhes. The name is admittedly interesting, but we need to consider the following about this name:

- We don’t know whether the Bedouins, who gave this place its name, had their facts straight. It was, after all, an event that had happened almost 2500 years before Flinders Petrie came to Tell Defenneh, and had been passed down by word of mouth. (If I used as my main evidence that a Bedouin had said this about the site I believe is Tahpnahes, I wonder how many people would listen to me.)

- We do not know when the site received this name. It could have just as easily been after Jeremiah came to Egypt. There were people at Tell Defenneh even after the Greek soldiers were removed. The Persians stationed a guard there,11 and it is well documented that there were Jews living in Egypt during that time in such places as Elephantine.

- It is not certain that the “Jew’s daughter” must be a king’s daughter, which opens up other possibilities. Marriages between Jews and Egyptians were not something rare and had been going on since the time of Joseph (Genesis 41:45). In I Chronicles 2:34-35, an Egyptian slave married an Israelite girl and in I Chronicles 4:18 an Israelite, who is not a king, married the daughter of Pharaoh.

- The only thing we know for sure is that Jeremiah went to Egypt with the king’s “daughters”. So there were at least two of them. But the name was “the palace of the Jew’s daughter” (singular), so it would not fit with the “daughters” that Jeremiah brought to Egypt. The palace/fort at Tell Defenneh was not large, especially compared to other palaces in Egypt, about 70 feet square,12 and it was not a stopover for foreign fugitives such as the “daughters of the king.”

ENDNOTES

1. Petrie, Flinders. Tanis II, 1888, p. 48

2. Petrie, Flinders. Tanis II, 1888, p. 51

3. Petrie, Flinders. Tanis II, 1888, p. 50

4. Strong, James. Strong’s Concordance, 1890, Hebrew Dictionary, #4404.

5. Petrie, Flinders. Tanis II, 1888, p. 50.

6. Petrie, Flinders. Tanis II, 1888, p. 50.

7. Gill, John. Exposition of the Bible, 1697-1771, note on Ezekiel 30:18. John, Bishop of Nikiu. Chronicles 72:15-18, who wrote at the end of the 7th century AD, translated in 1916 by Text and Translation Society. And Golb, Norman. Journal of Near Eastern Studies, Vol. 24, No. 3, The Topography of the Jews of Medieval Egypt, University of Chicago Press, July, 1965, p. 269.

8. Petrie, Flinders. Tanis II, 1888, p. 49.

9. Jeremiah 44:10.

10. Petrie, Flinders. Tanis II, 1888, p. 51.

11. Herodotus. Herodotus II, 30, 440 B.C., translated by Campbell, George. 1915.

12. Petrie, Flinders. Tanis II, 1888, plate XLIV.

In the Bible Tahpanhes is a large place. But Tell Defenneh is some mounds of sand, brush and some badly deteriorating bricks. In four places in the scriptures1 the town of Tahpanhes is mentioned alongside of Noph, which the scholars say is Memphis, the ancient capital of Egypt. Having Tahpanhes mentioned next to Noph shows the importance it had during that time.

Ezekiel was a contemporary of Jeremiah and wrote during the same time. In Ezekiel 30:13-19 he names the land of Pathros plus seven Egyptian cities including the city of Tahpanhes, which is found in verse 18 and spelled “Tehaphnehes.”

Ezekiel 30:13-19

v13. Thus saith the Lord GOD; I will also destroy

the idols, and I will cause their images to cease

out of Noph; and there shall be no more a prince

of the land of Egypt: and I will put a fear in the

land of Egypt.

v14. And I will make Pathros desolate, and will

set fire in Zoan, and will execute judgments in

No.

v15. And I will pour my fury upon Sin, the

strength of Egypt; and I will cut off the multitude

of No.

v16. And I will set fire in Egypt: Sin shall have

great pain, and No shall be rent asunder, and

Noph shall have distresses daily.

v17. The young men of Aven and of Pi-beseth

shall fall by the sword: and these cities shall go

into captivity.

v18. At Tehaphnehes also the day shall be

darkened, when I shall break there the yokes of

Egypt: and the pomp of her strength shall cease

in her: as for her, a cloud shall cover her, and

her daughters shall go into captivity.

v19. Thus will I execute judgments in Egypt: and

they shall know that I am the LORD.

Someone might think that the cities of Ezekiel 30:13-18 were listed from south to north or vice-versa but instead the Bible starts with the site of Noph, which is in the center of the country.

The “modern,” or Greek names of the first six cities are Memphis (Noph), Tanis (Zoan), Thebes (No or Multitude of No), Pelusium (Sin), Bubastis (Pi-beseth) and Heliopolis (Aven), and these are the names that the scholars will give them. The Greek names came from the Ptolemaic dynasty. These first six cities in this list of Ezekiel were all large cities in the days of Jeremiah, leaving you with the impression that for Tahpanhes to have been mentioned there, it would have to have been on equal footing with them. And these other cities have all had beautiful large stone temples found in them, some having multiple temples in them. They were all the capitals of their nome (province), and at least three of them, at one time, were the capital of the entire country: Memphis, Thebes and Tanis. All six of these cities have been excavated and large tooled stones were found at these sites, in most cases in abundance, with obelisks, pillars and statues of Pharaohs still lying there today. On the other hand, Tell Defenneh (Daphnai) has none of these. To try and compare Tell Defenneh to these other six large cities would be like comparing Miami, Chicago, New York, Philadelphia, Seattle, and Los Angeles with little Fort Laramie. It just does not fit. If Tahpanhes was a small city then it would have been the only one in this list that was.

The site only had three mounds; the main one being the fort and the palace, both made out of mud bricks, and the other two covered by sand, one from Ptolemaic times and the other from Roman times.2 These last two mounds did not exist in the time of Jeremiah the prophet, coming hundreds of years later. Today you will find no stones lying there on the ground, no statues, etc., only a few pieces of broken clay pots, some deteriorated mud bricks and sand. Mr. Petrie found no stone temple there, though he searched for one. “I searched in every direction for stone chips or broad walls that would indicate the site of a Greek temple, but was unsuccessful”.3 (A temple has recently {2009} been found at Tell Defenneh, but it was made out of mud bricks and has eroded away. I am not belittling the significance of this find, but such a temple would not compare to the beautiful stone temples found in the other cities mentioned before.)

Of course just finding a temple at Tell Defenneh would not prove that the site was or was not Tahpanhes. But I wanted to show that Tell Defenneh was small and did not compare to the other cities in Exekiel, Chapter 30, all of which have had beautiful stone temples found in them. And because of this, it would be “expected” that the city of Tahpanhes would have temples also. The Phoenician letter (more later) says, “all the gods of Tahpanhes”, if Tell Defenneh were Tahpanhes there should have been several temples there for “all” these gods.

Nebuchadnezzar’s throne. In Jeremiah 43:9, where it records the burying of the “great stones” in the city of Tahpanhes, the next verse says King Nebuchadnezzar’s throne would sit above these stones. It would in effect have been his headquarters while in Egypt. Then in verse 12 it says that God would use Nebuchadnezzar to destroy “the houses [temples] of the gods of Egypt; and he shall burn them....” This may have been the reason why Nebuchadnezzar chose to have his throne sitting outside of the palace instead of inside, because the palace may have also been burned, as well as the temples. Of the seven cities listed in Ezekiel 30:13-18, only of this city is it said, “At Tehaphnehes [Tahpanhes] also the day shall be darkened...a cloud shall cover her.” If a large city with all of her temples burns, you may well have the sky darkened and covered by a cloud. Nebuchadnezzar was not on a goodwill tour, but had come to destroy; and in particular, to burn the temples of the gods of Egypt. Twice in Jeremiah 43:12-13 it says that Nebuchadnezzar would burn the temples of the gods of Egypt. Would it not be expected of Nebuchadnezzar, therefore, to go to a large city with lots of temples because he had been sent to burn temples? Would not the city of Memphis fit well with all of its temples? Mr. Petrie said, “In such a center [Memphis] it was natural that the gods of many different cities should have a home, and the temples of nineteen gods are mentioned in various sources.” (Petrie, Flinders. Memphis I, 1908, p. 2.)

Not only was Tahpanhes large but it was very large! Consider the following.

(1) In Jeremiah 2:16, where it talks about judgment that came upon Israel, it only names two Egyptian places that took part in this. “Also the children of Noph and Tahpanhes have broken the crown of thy head.” Even if someone did not know what location Noph was believed to be (Memphis), you could not help get the impression that these two were the biggest, most powerful in Egypt, for they are the only ones named.

(2) There is not another Egyptian city in the Bible that is named more than the city of Tahpanhes, named seven times in the scriptures. This is not counting the queen by this name, nor the city of “Hanes” (Isaiah 30:4), which many believe to be a contraction of the name Tahpanhes. By contrast the city of “Pi-beseth” (Bubastum) is only given one time in the scriptures, and the city of “Sin” (Pelusium) is given just twice. Both of these cities are in the list of the seven largest cities of Egypt in Ezekiel 30:13-19. Even the name of “Noph” is only given seven times, and it is believed to be the city of Memphis. The next most named city is “Zoan” (Tanis, the capital of Egypt during the 21st Dynasty) which is given five times (There are two more times but it is the “field {country} of Zoan” and not the city.) I believe that knowing the size and importance of these other cities, one would expect Memphis to be named the most, but not Tell Defenneh. It is true that one of the reason Tahpanhes is mentioned so much in the Bible is because of the Jews who are living there, but so is Noph at least one time (Jeremiah 44:1). But this was not the reason Tahpanhes is named with Noph in Jeremiah 2:16 or with the other six cities of Ezekiel 30:13-19.

(3) In Ezekiel, Chapter 30 where the seven Egyptian cities are listed, Tahpanhes has the most said about it, and the description of this city is of a very large place. “At Tehaphnehes [Tahpanhes] also the day shall be darkened, when I shall break there the yokes of Egypt: and the pomp of her strength shall cease in her: as for her a cloud shall cover her, and her daughters shall go into captivity” (Ezekiel 30:18). There is no other Egyptian city in the Bible that has any one of these things said about it. I will expand on these three things - “her daughters,” “yokes of Egypt,” and “pomp of her strength,” – as they are used in scripture and it will be obvious that Tahpanhes could not be Tell Defenneh.

(a) In such a context in the Bible, it is not uncommon for the word “daughter” to be used as an expression for a city or cities; “the daughter of Jerusalem”, the “daughter of Tarshish”, “the daughter of my people”, or “thine elder sister is Samaria, she and her daughters that dwelt at thy left hand.”4 “When thy sisters, Sodom and her daughters, shall return to their former estate, and Samaria and her daughters shall return to their former estate, then thou and thy daughters shall return to your former estate”.5 Tahpanhes would have to be large enough to have “daughters” or other cities dwelling around it. Again the largest cities in Egypt are believed to be in Ezekiel 30, but only Tahpanhes is said to have these cities “daughters” around it. If Tell Defenneh had these other cities around it, then where are they?

(b) God said at Tahpanhes that He would “break the yokes of Egypt.” In the Bible the yokes of a person, king, or a country meant that someone was ruling over another. “[A]nd shalt serve thy brother; and it shall come to pass when thou shalt have the dominion, that thou shalt break his yoke from off thy neck”,6 “saith the LORD of hosts, that I will break his yoke from off thy neck....7 Here the Lord was speaking to Israel of a future time when it would not be under the control of a foreigner. “I will afflict thee [Judah or Jerusalem] no more. For now will I break his yoke from off thee, and will burst thy bonds in sunder.”8 There are many more such passages in the Bible and they refer to someone or some nation lording it over another. And God said at Tahpanhes “I shall break there the yokes of Egypt”. This would best fit Memphis, which was the first capital, and when not the capital, because of its size and location, remained the political and administrative center. However, the city of Sais was at this time (when Jeremiah was there) the home of the 26th Dynasty, and cannot be overlooked as a possibility. But how could Tell Defenneh be Tahpanhes of the Bible where God said He would “break the yokes of Egypt”? Tell Defenneh was not ruling over anyone. This could not be referring to Tell Defenneh that was never the capital of even its nome. Again no other Egyptian city in the Bible is given such a description.

(c) Also no other Egyptian city in the Bible is said to have “pomp”. Some would see in “pomp of her strength”, the pride of her fort, because it was a large fort. But some fifteen miles northeast of Tell Defenneh was the city of Pelusium whose fort was much larger, believed by some to be the largest in Egypt. If such an expression was in reference to the pride of their fort’s strength, then it would have been said of Pelusium, not Tell Defenneh. There are two more times when the word “pomp” is used in connection with this country. “[T]hey shall spoil the pomp of Egypt...”,9 but as you can see this is in reference to the country of Egypt. Also “Egypt shall fall; and the pride of her power shall come down…”10 The word “pride” in this verse, in the Hebrew, is the same word translated the “pomp” of Tahpanhes in Ezekiel 30:18, and the word “power” is the same word translated “strength”. It is in fact the same expression as “pomp of her strength” as found in the Ezekiel 30 passage about the city of Tahpanhes. Again, it is in reference to the whole nation. And so, are we to believe little Tell Defenneh is supposed to merit such an expression as “pomp of her strength”, but no other city in Egypt could, only the whole nation itself? As to the word “pomp”, this has the meaning of “excellency, majesty, pomp, pride”.11 It is talking about a royal city, not a desert fort for Greek mercenaries. Such a description would best fit a city like Memphis, Tanis, Sais or Thebes that at one time ruled all of Egypt. Of course, this would not fit Tell Defenneh.

Mr. Flinders Petrie quoted from the Apocrypha book of Judith 1:9-10 (1st century B.C.), which mentions the city of Tahpanhes. This is an account of a hero named Judith, where a foreign king, whose empire includes Egypt, writes to specific cities in his kingdom. Flinders Petrie quotes from it to show the importance that was placed on the city of Tahpanhes by the writer of the book of Judith, and I agree. Only three Egyptian cities are named in this book (four if “Ramses” is a city instead of a land13) with Tahpanhes being one of them, giving you the impression it must be one of the biggest in the country. But if Tahpanhes was Daphnai (Tell Defenneh) then the book of Judith should have also mentioned Pelusium because it was a much larger city than Daphnai, with a much larger fort and it was in the same area.

In connection with this, there is The Pilgrimage of Etheria, (whose author is also known by the names Silvia and Egeria, written in 385 A.D., translated by McClure, 1918.) She tells about her trip to the Holy Land including the Sinai desert and Egypt. The Pilgrimage of Etheria has been used to make Tahpanhes fit with the location of Tell Defenneh (Daphnai). Etheria talks about visiting a city named “Tatnis,” while in the Nile delta. Some see the city of Tanis in this name while others the city of Tahpanhes (which they believe is Tell Defenneh). These two ancient cities, Tanis and Tell Defenneh, were about twenty miles apart. She said, “Through the land of Goshen continuously, we arrived at Tatnis, the city where holy Moses was born. This city of Tatnis was once Pharaoh’s metropolis.” As to Moses being born at Tanis, some do believe this. But no one believes Moses was born at Tell Defenneh. And this city being “once Pharaoh’s metropolis” was true of Tanis, but again, no one believes this of Tell Defenneh.

It is of interest that the name Tahpanhes is found in the Dead Sea Scrolls14 (and other ancient records) but without the location being given.

ENDNOTES

1. Jeremiah 44:1, 46:14, Ezekiel 30:13-18, and Jeremiah 2:16.

2. Petrie, Flinders. Tanis II, 1888, p. 79, plate. XLIII.

3. Petrie, Flinders. Tanis II, 1888, p. 60

4. Ezekiel 16:46.

5. Ezekiel 16:55.

6. Genesis 27:40.

7. Jeremiah 30:8.

8. Nahum 1:12-13.

9. Ezekiel 32:12.

10. Ezekiel 30:6.

11. Strong, James. Strong’s Concordance, 1890, Hebrew Dictionary #1347.

12. Petrie, Flinders. Tanis II, 1888, p. 50.

13. Genesis 47:11, Exodus 1:11.

14. Wise, Abegg and Cook, Dead Sea Scrolls, A New Translation, Harper Collins Publishers, 1999, 4Q384-5b

Tahpanhes is Memphis the ancient metropolis of northern Egypt! The evidence for Tahpanhes being Memphis is more and stronger than for Tell Defenneh being Tahpanhes. But first I will need to explain why Memphis is not “Noph”, as most all believe (please see map at the beginning).

There are two Bible names that people believe represent the site of Memphis. They are “Noph” and “Moph”, with most people believing that Noph is a corruption of the name Moph. And a few think that Noph is a corruption of Na-Ptah, “They of Ptah”, Ptah being the main god of Memphis and thus another possible name for this city, and some who at one time thought that Noph might be Napata, the ancient capital of Nubia. But I will spare you the explanations as to why they are wrong as no one today believes these.

“Moph or Noph?”

These two may sound like a brothers’ comedy team, “Moph & Noph,” but they are not related. Moph is translated as “Memphis” in our English Bible (Hosea 9:6 KJV), but they did not translate “Noph” to Memphis, showing that they had doubts about this. The Jews already used “Moph” for Memphis in Hosea 9:6, which was more than 40 years before the first time “Noph” is mentioned in Isaiah 19:13. They could hear the M in Memfi and there would be no reason to start changing this name to have an N on the front to become Noph, especially since no one else (Assyrians, Copts, Arabs, etc.) pronounced this city with the letter N.

The Greek name Memphis came from the city’s ancient name of Men-nefer becoming Mn-nfr, Menfi, Memfi, or Membi in late Egyptian. Egyptian hieroglyphics did not use vowels. Also their r was almost silent and dropped by the Assyrians and Copts, and is not found in the Arabic and Targums. The Hebrew Bible transliterated the Egyptian f with ph, hence “Moph.” But I found no one who gave the ancient name for Memphis as beginning with the letter N.

The Encyclopedia Biblica, A Dictionary of the Bible, Volume III, 1902, has some interesting comments on these place names Noph and Moph. “Strangely, the correct orthography is found in MT [Masoretic or Hebrew text] only in one passage, Hos. 9:6, where Moph...The name of the city is written in Egyptian Mn-nfr? Vocalized Men-nofer, later Men-nufe or shortened Men-nefe, Menfe. Targum Mephis, Assyrian Mempi, Mimpi. The Copts wrote Menbe, Membe, Memf, Mefe, whence Arabic Manf (sometimes Munf?) and later Maphe. Thus we should expect the pronunciation Memp in Hebrew; the present punctuation Moph, Noph needs explanation.”

In the Jewish religion, there is a well-known text called the Haggadah, that gives the order of the Passover. It is to be read every year, and it says, “Thou didst sweep the land [soil] of Moph and Noph, when thou didst pass through on the Passover”.2 Tradition has this text being compiled during the Talmudic period, or roughly the 2nd century. But today we read that Noph was another way the Jews had to pronounce Memphis, or it was a “corruption”, “variant”, “error”, etc. These all basically say the same thing, that for whatever reason, the Jews had two ways to pronounce the same place, either Noph or Moph. But for at least 1,800 years, the Haggadah has had it as two different places, “Moph and Noph.”

I had been following the belief that Noph was a city, but I now believed it was an area within the borders of Egypt. In The Monumental History of Egypt, Vol. II, 1854, by William Osburn, p. 218, the author quotes an inscription of Pharaoh Thothmosis that was on the walls of a palace at Karnak. The name Noph is found here with the determinative (that explains how the word is to be understood) for a “desert or foreign land”, not the determinative for a city. But Mr. Osburn, of course, believed as everyone else did, that Noph was the city of Memphis. Why then does it have the determinative for a land? He said, “This mode of writing the name of a city in Egypt denotes it to have been at that time in the hands of another power.” Later on p. 260, he talks about a red granite monument found at Thebes. On this monument it tells about a battle fought in “the land of Noph”, and then on p. 263 it is the “district of Noph”, again the determinative for both of these is for a “desert or foreign land”, not the one used for a city. Mr. Osburn is then forced to conclude, “By the Noph of the inscription before us we are to understand the city of Memphis with its surrounding nome or province,” p. 261. I could see Memphis being a city in the “land of Noph,” (“surrounding nome or province”), just as Los Angeles is a city in the state of California, but not one and the same place. I have asked different archaeologists if the name Noph has ever been found with the determinative for a city, and up until now, no one has been able to confirm this. “But all the prominent biblical archaeologists believe that Noph was Memphis!” Yes, but that is not the question I asked. Not only has the name Noph been found three times in Egyptian hieroglyphics (The Monumental History of Egypt, Vol. II. by William Osburn, pp. 218, 260-263), it is always with the determinative for a land. This being so, it would mean that Memphis (Moph) is only recorded once in the Bible, unless it is, as I believe, also called Tahpanhes. It will be explained later at which time periods the city used which name and why, but because it was the largest city in Egypt and in close proximity to Judah (not hundreds of miles away in southern Egypt), one would expect this city to be named the most.

The name “Pathros” in the Bible is for the land of southern Egypt, but most of the times this name is given, it is not called a land or a country. Also, the name “Sheba,” believed to be a foreign land or country, is mentioned 17 times in the Bible (which also includes references to “Queen of Sheba”, “Kings of Sheba”, “merchants of Sheba”, as well as listings with other countries) and only one time is it called a land or a country. It should not be surprising, then, if Noph is a land but is not called that in the Bible. Someone might have a problem making Noph a land because it is spoken of in parallel next to a known city, “Surely the princes of Zoan are become fools, the princes of Noph are deceived...”3 but compare this with the land of Judah and the city of Jerusalem, “The princes of Judah, and the princes of Jerusalem....”4 This also shows that to have “princes,” a location does not have to be a city, but can be a land such as Judah. And compare “Also the children of Noph and Tahpanhes...”5 with “the children of Judah and Jerusalem...”6

ENDNOTES

2. Meagher, James L. How Christ Said the First Mass, 1908, Haggadah p. 431.

3. Isaiah 19:13.

4. Jeremiah 34:19.

5. Jeremiah 2:16.

6. II Chronicles 28:10.

Oxford Sackler Library

Nancy and I went to Oxford, England, where we spent parts of four days, January 9-12, 2008. I put in for translation the Phoenician letter about “all the gods of Tahpanhes”, which includes about 30 pages of notes. I especially wanted this complete Phoenician letter because I hoped it might have more to it and even possibly help identify the site. (It did!) This letter was found at Memphis not Tell Defenneh. This in itself does not prove that Memphis was Tahpanhes but does give Memphis a 50/50 chance. This will be brought up again in more detail, but for now the only point I am making is that it has been proven that either the person who wrote the letter or the one who received the letter had to be living there and worshiping all these “gods of Tahpanhes”. Memphis therefore would qualify, not only because of her size and her nineteen temples, but also because the only place in Egypt where the name Tahpanhes has ever been found was at Memphis. (This letter was written in Aramaic and is why they will say the name Tahpanhes has never been found in Egyptian “hieroglyphics”.)

The Phoenician letter. In January, 1940, Mr. Noel Aime-Giron began the study of the then newly found letter about “Baal Saphon and all the gods of Tahpanhes”. This letter had been found at Saqqara (the necropolis of Memphis). Mr. Aime-Giron made the translation and comments that will follow. But before we get to these, I want to quickly go over a couple of other things he brought up in his article.5 Not only is it believed that Tell Defenneh is Tahpanhes of the Bible but some scholars believe it is also “Baal-zephon” of Exodus 14:2. And this is believed because of the article by Mr. Aime-Giron. His theory is based on two things. First, he believes that because Baal-zaphon was the only god whose name is given in the Phoenician letter, that therefore he was the main god and thus the *city took its name from this deity. Of course, this is all based on the supposition that Tell Defenneh was Tahpanhes. But those who worshiped Baal-zaphon also identified it with Ptah6 the main god of Memphis. So it would fit to have Baal-Zaphon being the main god of Memphis. However it is logical to believe that the reason Baal-zaphon is mentioned in the letter was because the person who wrote this letter and the one to whom it was addressed, according to Mr. Aime-Giron,7 were both Phoenicians. And this god was the main god in their home country of Phoenicia, so they would naturally mention it before others.

*(I do not believe the Baal-Zephon of the Red Sea crossing, was at the site of Memphis or any city. The Jews consistently make Baal-Zephon and idol, or a place with an idol and its temple. Josephus did not say that Baal-zephon was a city, but only called it a “place.” “[O]n the third day they came to a place called Beelzephon….” [Josephus. Antiquities, II, 15, 1]. Other Jewish sources say that Baal-zephon was an idol: “before the idol Zephon” [Targum Jonathan also Targum Onkelos, both 3rd century AD]. Legends of the Jews said that Pharaoh “hastened to offer sacrifices to him [Baalzephon, where]...the great sanctuary of Baal-zephon was situated.” “Of set purpose God had left Baalzephon uninjured, alone of all the Egyptian idols. He wanted the Egyptian people to think that this idol was possessed of exceeding might, which it exercised to prevent the Israelites from journeying on” (Legends of the Jews, III, Pharaoh Pursues the Hebrews; also Targum Jonathan, Exodus XIV.)

Secondly, Mr. Aime-Giron cites a stela8 in the Cairo Museum that has the god of Baal on it and was said to have come from Tell Defenneh. Whatever else might be said about this stela, it is, at the least, interesting in that it has this foreign deity of Baal on it mixed with hieroglyphics and Egyptian symbols. But it is less than convincing that this stela ever came from Tell Defenneh. Mr. Noel Aime-Giron said that, “The Journal of Entry of the Gizeh Museum, recorded it [the stela], by mentioning: ‘Alexandria, July 1881, purchased.’” Then in the “Notice of the principal monuments shown in the Gizeh Museum, published in 1897 by Grebault (nr. 438)...its origin is given as Lower Egypt. It is only in 1906, in his Egyptological Researches, that Max Muller. added: ‘I can add to it that after a communication from the obliging conservator, Mr. G. Daressy, the stone has been found at a highly interesting place, at Tell- Defen.’”9 The museum originally said it was purchased at “Alexandria, July 1881,” apparently by some merchant of antiquities, then in 1897 we are told it came from “lower Egypt”, which has dozens of cities and would include both Alexandria and Tell Defenneh, then nine years later in 1906, we are told it came from Tell Defenneh. Well, maybe yes and maybe no. It would have been helpful if Mr. Daressy had said how the information came to him, but it is not given. For the sake of the argument it is at least a possibility this stela came from Tell Defenneh, but I do not see this proving the main god there was Baal. I quoted Mr. Flinders Petrie who said the main group of people there were Greeks10 and Baal-zaphon was not one of their deities. I do not doubt the possibility of this god being worshiped there by someone who was Phoenician, but certainly it was not the main deity. When Mr. Petrie excavated the site of Tell Defenneh, he did find artifacts of different Egyptian gods such as Ptah, Sokar, Isis, and Horus,11 but Mr. Petrie did not find Baal-zaphon or any other Baal at Tell Defenneh.

Paleography. As to the Phoenician letter, Mr. Giron said some interesting things in a section he entitles “Paleography and the age of the Document.” The studying and deciphering of ancient writings is an amazing science, leaving you with the impression that we can know more about the letter than the person who received it. And all this is done through the eye of the microscope that looks back in time some 2600 years. I will give a brief part of his comments found in his article12 along with the actual letter itself and will then comment on it.

After he discusses the script used in the letter, he concludes that it was written about the time of “the epoch of Amasis.” Amasis was a Pharaoh of the 26th Dynasty and ruled Egypt from 570 to 526 B.C. This letter was a private letter between two sisters. The one sister “Bas’u” (who he believed was living at Tahpanhes) had sent a letter to her sister “Arisuth” who was living at Memphis. Bas’u acknowledges having received some funds from her sister, Arisuth, which she used to meet some legal obligation. Unfortunately, after 2,600 years some of the letters and words have “fallen off,” and this is shown by a blank space ____ or are no longer readable and he has marked the space where the word would have been with “?”.

The outside or back of the letter: “To Arisuth daughter of Esmunyaton”

The inside of the letter: “I tell my sister Arisuth, your sister Bas’u says: Since you are in good health and me too, you return your blessings to Ba’al Saphon and to all the gods of Tahpanhes so that they keep you in good health. The money that you sent me arrived; that produced me weight (in sequels) 3˝ 1/6 (?) (one more) q(uart)? ____ ____ ____. I lavished in addition (?) all the money that belonged to me more of yours (?) and I gave it to _____ have confidence in ____ that I know in this ____. You sent me the acquittal manuscript (?) I will pay it to his ____.”

The letter is less than impressive, but his commentary on this letter is enlightening.

“This white space [blank space on the outside of the letter] had to be used for the seal, and the tear of the papyrus just after the word [he gives the original script] seems to have occurred when the envelope was opened…It seems even that small fragments of virgin wax [the seal] still adhere, here and there, on the front of the document where they would have remained attached after the pleat opening by the addressee…The fifth line and the address on the back, on the contrary, makes you understand that she used a worn tool and betrays a certain haste, confirmed by the absence of the points of separation. One has the impression that the sender wrote these last ones [lines] with a reed near at hand at the moment of giving her letter to the messenger, and maybe even outside of her place [house]. The ink tracks, on the left corner of the bottom margin, confirm this diagnosis: they are in fact copies [stains] of the two last signs of line four and prove that the document was folded while the ink was still fresh at this point.”

His comment now on the words “acquittal manuscript.” - “I suspect that it had to be here a question of a disputed matter in front of the civil or religious administration and for which the letter’s author would have poured funds.” The question of which sister lived at Tahpanhes becomes important and it is something Mr. Aime Giron flip-flops on. “It would seem, no doubt, at first sight that the sender, the Phoenician Bas’u, lived at Tahpanhes and that the addressee, another Phoenician, (Arisuth) was settled or passing through Memphis.” Then he is forced to change his mind and says, “This is nevertheless not as certain as it here appears at first interpretation....If it is a question of a disputed matter either with a civil jurisdiction, or in front of a religious authority, one would be astonished that such administration of this importance could exist at Tahpanhes.” I would agree to this if Tahpanhes was Tell Defenneh, as he believes. He goes on to say that a person living at Memphis, the administrative capital of Egypt, would have such courts. “In this case, there would remain a single solution: to suppose that the letter never left Memphis and that, despite the haste brought by the sender to finish her letter, this one missed the mail.

Really? There is no explanation of how it “missed” the mail, but on the other hand, he did give a long explanation on how the sender had made “haste” to get the letter to the “messenger”. He did tell us it had a “seal”, and that some “fragments” of the seal still remained attached after the “opening by the addressee”. But we are to forget all of this. He goes on to say, “The roles then would be inverted: Bas’u would have lived in the capital and Arisuth in the military village of Tahpanhes.” I could not help but laugh when he called Tahpanhes a “bourgade” (French for “village or small town”). Remember, he believes Tahpanhes is Tell Defenneh. “One can, I think, call thus Tahpanhes although this locality is quoted seven times in the Old Testament and almost always with cities of a lot greater importance.”13

Well, Amen! Mr. Aime-Giron was the first person I read that agreed with me that Tell Defenneh would not compare in size with the other great cities of ancient Egypt.

So, what has been said? Though Mr. Aime-Giron wants to believe that this Phoenician letter had been “sealed” and “haste” was made to get it to the “messenger” and “opened by the addressee”, yet he was not able to, even though his own evidence he had brought forth supported this! Why? Because he had been told that the biblical city of Tahpanhes was Tell Defenneh. For two years I also believed this, but I got tired of forcing a square peg into a round hole!

ENDNOTES

5. Aime-Giron, Noel. ANNALES DU SERVICE DES ANTIQUITES DE L’EGYPTE, Imprimerie De L’institut Francais D’Archeologie Orientale, published in Egypt, 1940, Volume XL, pp. 432-460.

6. Aime-Giron, Noel. ANNALES DU SERVICE DES ANTIQUITES DE L’EGYPTE, Imprimerie De L’institut Francais D’Archeologie Orientale, published in Egypt, 1940, Volume XL, p. 454.

7. Aime-Giron, Noel. ANNALES DU SERVICEDES ANTIQUITES DE L’EGYPTE, Imprimerie De L’institut Francais D’Archeologie Orientale, published in Egypt, 1940, Volume XL, p. 443.

8. Aime-Giron, Noel. ANNALES DU SERVICE DES ANTIQUITES DE L’EGYPTE, Imprimerie De L’institut Francais D’Archeologie Orientale, published in Egypt, 1940, Volume XL, p. 447, Stela Nr. 25147 of the Cairo Museum.

9. Aime-Giron, Noel. ANNALES DU SERVICE DES ANTIQUITES DE L’EGYPTE, American University in Cairo Pres, published in Egypt, 1940, Volume XL, p. 448.

10. Petrie, Flinders. Tanis II, 1888, p. 48.

11. Petrie, Flinders. Tanis II, 1888, plate XLI.

12. Aime-Giron, Noel. ANNALES DU SERVICE DES ANTIQUITES DE L’EGYPTE, Imprimerie De L’institut Francais D’Archeologie Orientale, published in Egypt, 1940, Volume XL, pp. 432-460.

13. Aime-Giron, Noel. ANNALES DU SERVICE DES ANTIQUITES DE L’EGYPTE, Imprimerie De L’institut Francais D’Archeologie Orientale, published in Egypt, 1940, Volume XL, pp. 432-460.

But if Memphis is Tahpanhes then the problems dissolve.

There were some things said in the Phoenician letter that show not only that the person who was to receive it lived at Tahpanhes, but that Memphis would have been Tahpanhes. The writer said, “you return your blessings to...all the gods of Tahpanhes....” The Phoenician lady who wrote this letter would not have told her sister to do this unless she lived at Tahpanhes. One would naturally expect a person to be living at Tahpanhes if she is to give her blessings to “all the gods of Tahpanhes”. Some might think that one could pray to God anywhere. Yes, for the true and living God, but most of the world then was polytheistic with all these “gods” who, for the most part, were localized in certain centers. This was the mindset of the Syrians who, referring to Israel, said, “Their gods are the gods of the hills; therefore they were stronger than we; but let us fight against them in the plain, and surely we shall be stronger than they.” This was a big mistake on their part! “Thus saith the LORD, Because the Syrians have said, The LORD is God of the hills, but he is not God of the valleys, therefore will I deliver all this great multitude into thine hand, and ye shall know that I am the LORD” (I Kings 20:23 & 28). If the sister who wrote the letter thought she could have blessed “all these gods of Tahpanhes”, she would have done it herself. Instead, she asked her sister to do what she felt she could not, otherwise why ask her? Simply put, the one who wrote the letter did not live at Tahpanhes. This will become important with what follows.

Mr. Aime-Giron originally believed that the writer had “given her letter to the messenger”, and that it was received and “opened…by the addressee.” But all this was discarded because the letter was found at Memphis and he believed Tahpanhes was Tell Defenneh. He then changed his mind, saying that instead of being sent from Tell Defenneh it was being sent to Tell Defenneh, but never got there because it “missed the mail”. I purposely repeated this from what had been given earlier so it would be fresh in your mind to appreciate what follows. The writer, who Mr. Aime-Giron believed lived at Memphis, said, “You sent me the acquittal manuscript.” But Mr. Aime-Giron told us that Tell Defenneh was too small a place to have a court. “If it is a question of a disputed matter either with a civil jurisdiction, or in front of a religious authority, one would be astonished that such administration of this importance could exist at Tahpanhes.” He then called Tahpanhes (which he believed was Tell Defenneh) a “village”. With that said, how could a person living in Memphis write a letter to someone living in the “village” of Tell Defenneh and say, “You sent me the acquittal manuscript”? For as Mr. Aime-Giron said, it was too small a place to have a court; “one would be astonished”, it simply was not possible.

But if Memphis is Tahpanhes then this letter would have been written and given a “seal” from whatever city it was sent from; the writer then “giving her letter to the messenger” (as Mr. Aime-Giron had originally believed), and the letter being “opened…by the addressee” where it was found, at Memphis. Which would make this the city Tahpanhes because only a person living in this town could have done what was asked, “you return your blessings to...all the gods of Tahpanhes.” And the person who sent the letter acknowledges receiving the “acquittal manuscript” from Memphis, which was large enough to have such courts. So nobody has to “miss the mail” because of Tell Defenneh!

Why would the Egyptians name a city after someone from another country? I have read a half dozen possible meanings of this name Tahpanhes but will only give here the main view that is held today. “Mansion of the Nubian”2 is believed to be the meaning of the name Tahpanhes. I have read different variations such as “The House”, “The Palace”, “The Fortress”, or “The Castle” for Tahpa, of Tahpa-nhes. And they will tell you that the ending nhes refers to people living south of Egypt. It is usually translated Chushite, Nubian, or Ethiopian. This was the view held by Mr. Noel Aime-Giron who translated the Phoenician letter about “Baal Saphon and all the gods of Tahpanhes”, and was originally put forth by the German Egyptologist Wilhelm Spiegelberg,3 and as I said, it appears to be the main view held today. What town would be named “Mansion of the Nubian”? I cannot imagine Psamtik I of the 26th Dynasty, who built Tell Defenneh for his Greek soldiers naming it after a Nubian. Flinders Petrie found no evidence of Nubians being at Tell Defenneh, or Jews for that matter, but there was evidence for both at Memphis.4

With the name Tahpanhes meaning “Mansion of the Nubian”, one would expect two things: this city should have had an important Nubian living there, and be a royal residence. The great stones were to be hid at the “entry of Pharaoh’s house in Tahpanhes” (Jeremiah 43:9), which is what we should be looking for in connection with “Mansion (Pharaoh’s house) of the Nubian”. But what could have been the motive for the Egyptians to name a very large city, or any city, after someone from another country?

If someone called the largest city in your state the “Mansion of the Ethiopian”, you would naturally expect that an important Ethiopian ruled or controlled the city at one time. The 25th Dynasty ruled from Memphis and is known as the Chushite or Nubian Dynasty, starting with King Piye from 752 B.C. until King Tantamani in 656 B.C. The Nubian Pharaoh Taharqa had his coronation at Memphis. “I [Taharqa] received the crown in Memphis”.5 The Pharaohs who ruled in this time period were called by foreigners “kings of Ethiopia”, even though the 25th Dynasty ruled from the ancient capital of Memphis. The Bible says, “And when he heard say concerning Tirhakah [Taharqa] king of Ethiopia… [Kuwsh, Heb.]”;6 this was also done by the Assyrians who invaded Egypt in 671 B.C.7 Of more interest is something said by Esarhaddon, the king of Assyria who drove out the Nubian Pharaoh, Taharqa. He twice calls Memphis “his (Taharqa’s) royal residence,”8 (from the Sinjirli and Dog river stelae), which shows that not only did this Nubian king live at Memphis, but how natural it would be for this city to end up having such a name as Mansion of the Nubian, “His (the Nubian’s) Royal Residence”.

King Esarhaddon of Assyria still called Memphis by its old name “Me-im-pi,” which I believe it continued to have. Piye, the first king of the 25th Dynasty, called Memphis “Men-nefer”, “Abode of Shu”, “White Wall”, and “The Balance of the Two Lands” all on one stela, so the city was called by more than one name at a time.9 Memphis had many names and the ones given here by Piye are well known and used by others. There really are not many possibilities where such a name as *“Mansion of the Nubian” (Tahpanhes) could have come from, but the Nubian Dynasty is obvious. *(This name may have been given by the Egyptians and not the Nubian Kings.)

The name “Moph” (Memphis) found in Hosea 9:6 is from about the year 760 B.C., and it is the only time in the Bible the name is used. This name “Moph” in the Bible would have been used before the beginning of the Nubian Dynasty. This would help explain why Moph is not used again, as the new name Tahpanhes started to be used more, sometime during the Nubian or 25th Dynasty. It also explains why the name Tahpanhes is not used before this time. The first time the name Tahpanhes is used is in Jeremiah 2:16, about 630 B.C. or 26 years after the Nubian Dynasty ended, and the last time is in Jeremiah 44:1, or about the year 582 B.C. And the Phoenician letter that mentions Tahpanhes would work with this time period. We are only talking about a 50-year time period when this name is used in the Bible. Yet no other Egyptian town in the Bible is mentioned more than Tahpanhes, and then mysteriously the name Tahpanhes seems to have fallen off the map. We never find it in Egyptian writings, but it appears in the Bible, the Dead Sea Scrolls, and the Phoenician letter. Did someone erase the name Mansion of the Nubian?

ENDNOTES

2. Aime-Giron, Noel. ANNALES DU SERVICE DES ANTIQUITES DE L’EGYPTE, Imprimerie De L’institut Francais D’Archeologie Orientale, published in Egypt, 1940, Volume XL, p. 444.

3. Aime-Giron, Noel. ANNALES DU SERVICE DES ANTIQUITES DE L’EGYPTE, Imprimerie De L’institut Francais D’Archeologie Orientale, published in Egypt, 1940, Volume XL, p. 444.

4. Petrie, Flinders. Memphis I, 1908, pp. 10, 40, 45, Memphis II, 1909, by Flinders Petrie, pp. 13, 17, 37.

5. Bianchi, Robert Steven. Daily Life of the Nubians, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2004, p. 167, (Kawa Stela V. line 15).

6. Isaiah 37:9, II Kings 19:9.

7. Driver, Gardner, Griffith, Haerfield, Headlam and Hogarth, Authority and Archaeology, 1899, p. 110.

8. Grimal, Nicolas. A History of Ancient Egypt, 1992, Blackwell Publishing, p. 350.

9. Budge, Wallis, E. A. Egyptian Literature, Volume II, Annals of Nubian Kings, 1912, p. 38-45

Erased. At different places in Egypt a name of a pharaoh has not been found because it was erased or written over. There were different reasons for this. Sometimes it was simply to usurp another’s monument or for a political reason; but more often than not, it was because the pharaoh was not liked. The two most outstanding examples of this are Pharaoh Akhenaten and the powerful Queen Hatshepsut. There is disagreement as to why their names were erased, yet it is agreed there was a deliberate attempt to erase their names from history. I have asked archaeologists if they had heard of a city’s name being removed or erased. Their response was “No”, they only knew of names of people or some of the gods (Amun) being erased. Yet, I did find three names of cities that have been erased.1 There must be a reason why a name of a city that is used so many times in the Bible has never been found. Erasing of the site name is a possibility, but what would be the motive?

The Nubian or 25th Dynasty came to an end when the Assyrian Empire invaded Egypt and pushed them into Ethiopia (Sudan). The Assyrians then set up minor kings in the delta area of Egypt and also changed the names of these cities during their brief reign there.2 To my knowledge, these Assyrian names for these Egyptian cities cannot be found today in Egyptian hieroglyphics, as the name of Tahpanhes cannot. Within a few years the Assyrian Empire collapsed and then the 26th Dynasty began ruling from Sais in the West Nile Delta. Relations between the new 26th Dynasty and the former Nubian rulers started off well enough with King Psamtik I of the 26th Dynasty marrying a Nubian princess and leaving the Nubian high priestess and Nubian mayor in place at Thebes. Then during the reign of Pharaoh Psamtik II something happened - a wholesale erasure of all the former Nubian names began. There is a very good article on this entitled “The erasing of the Royal Ethiopian names by Psammetichus II [Psamtik II]”.3 It shows that this was not just one person upset with a former king, but an attempt to erase an entire dynasty, which is called the “general persecution” of the Nubian Dynasty. This article gives 15 sites where the Nubian king’s name Piankhy (Piye) was erased and 16 sites where Taharqa’s name was erased, and their names often were erased more than once at each site, plus all the other kings in this dynasty. This came about because Psamtik II (595-589 BC) who went to war with, and invaded Nubia, erased the names of the former Nubian kings in their country, and upon his return to Egypt, had his name written over theirs. This also may have gone on after Psamtik II. Mr. Petrie had a similar find at the palace of Apries in Memphis4 which I believe was Tahpanhes. He gave a description of a “bronze corner of a door” and then said, “The cedar planking is still inside of it, fastened by bronze rivets passing through both plates. The inscription is of Psamtik II; but the surface is clearly lowered from the signs Hor to nebti, from Hor nub to taui, in the cartouche after Ra, and over the second cartouche. This suggests that Taharqa (the Nubian ruler) was the original maker, as his Hor nub name ends in taui, which is on the original face; moreover his Horus name would not project above the hawk, and the face of the bronze has not been lowered there.”

You can probably see where I am going with this theory. Psamtik II, while erasing the names of his Nubian enemy, would not have wanted Memphis, the biggest city in Egypt, named after them, “Mansion of the Nubian”; it would in fact be surprising if he did not get rid of this name! The time period that this happened would have been from his invasion into Nubia in 591 BC till his death in 589 B.C. The last time the name Tahpanhes is given in scripture is believed to be about seven years later in 582 B.C. in Jeremiah 44:1. Names do not die out overnight, as most people who lived through the Vietnam War still call the capital of South Vietnam, Saigon, even though officially it is Ho Chi Minh City. Besides, the Jews did not consider the Nubians an enemy, for Tahraqa had come to their aid against the Assyrians.5

ENDNOTES

1. Osburn, William. The Monumental History of Egypt, 1854, Volume II, pp. 217, 262-3 and 265.

2. Rogers, Robert William. A History of Babylonia and Assyria, 1900, Volume II, p. 316.

3. Yoyotte, Jean. (Revue D’Egyptologie, La Societe Francaise D’Egyptologie, Paris Imprimerie Nationale, 1950, “The erasing of the Royal Ethiopian names by Psammetichus II [Psamtik II],” pp. 215-239.

4. Petrie, Flinders. Memphis III, 1910, p. 40, plates XXXII 3, XXXIII 13.

5. II Kings 19:9.

Jeremiah buried the “great stones” at the entry of the king’s palace. This would have been during the time of Apries (Greek) of the 26th Dynasty, Vaphri (Latin) and Hophra (Hebrew – Jeremiah 44:30). We should be looking for a palace associated with this king. Because the “great stones” were to be hid at “Pharaoh’s house.”

Of the two palaces found at Memphis, one was Merenptah’s palace, which was several centuries before the time of Jeremiah, and the other was a palace built by Pharaoh Apries of the 26th Dynasty (even though at that time the official capital was at Sais). It was even called “the Palace of Apries”, by Flinders Petrie, and he gives this name as the original title for his book, Memphis II. It was again Mr. Petrie who did the main excavation on the Palace of Apries, working there in 1908-1910. Mr. Petrie called it a “palace fortress” and said, “The general scheme of the building was that it occupied the north-west corner of the great fortified camp of about thirty acres, at the north end of the ruins of Memphis.” (Memphis II, 1909, p. 1). And it was huge, just the courtyard itself, inside the middle of the palace, was over 100 feet square which would have swallowed up the palace of Tell Defenneh, which was only 70 feet square.1 The overall dimensions of the palace were 200 by 400 feet;2 it sat on a 13-meter-tall mound3 and the height of the palace itself was 50 feet above that.4

Tahpanhes being Memphis, we should find Baal-zaphon of the Phoenician letter there. Mr. Aime-Giron gives evidence for both Baal-zaphon and the Phoenician goddess Astarte being worshiped at Memphis.5 The goddess, Astarte, “The Queen of Heaven”, the foreigners took and assimilated or identified with the Egyptian goddess Isis, which was worshiped at Memphis, and she would be expected at the city of Tahpanhes. She is mentioned no less than four times in Jeremiah 44:17-25, where Jeremiah rebukes the Jews for worshiping her while they were in Egypt. This rebuke of Jeremiah to the Jews in Egypt was the last recorded message of a great prophet of God. It is believed that shortly after this he was stoned to death. In the end, none of these false gods could even save themselves because God had all their temples burned.6

It needs to be mentioned here that of all the cities the Jews could have gone to, the most logical place was Memphis, in spite of articles I have read that say Tell Defenneh (which they believe is Tahpanhes) would have been. Their reasoning is that because Tell Defenneh was right inside the border of Egypt, one would expect the Jews to have fled there. No, one wouldn’t! It should not be forgotten that the Bible says the Jews were also at Noph and Pathros (Jeremiah 44:1); these are in central and southern Egypt. If it were just a matter of distance so they could flee to the closest place, then one would expect them to go to another city that was nearer to Israel and in the same area of Tell Defenneh, and that was Pelusium, called “The Gateway to Egypt”, which had much more to offer.

But the main place they would have been expected to go was Memphis, because that is where they went the last time that their country was invaded by the Assyrians. In Hosea 9:6, where we find the city of Moph, and it is translated Memphis, it says that Israel would be buried at Memphis. This is not talking about the Egyptians and the people of Memphis invading Israel and burying the Jews in their own land as some have imagined, for verse 3, which was part of this passage (also verse 17,) is crystal clear. “They shall not dwell in the Lord’s land but Ephraim shall return to Egypt.” Moses had led them out of Egypt but Samaria (Ephraim) “shall return”. And verse 6 says “For, lo they are gone (Israel from their country) because of destruction; (by the Assyrians) Egypt shall gather them up, Memphis shall bury them.” And Memphis is the only Egyptian town mentioned in the passage. So, one would expect it to be the main one they would go to when the Babylonians invaded.

ENDNOTES

1. Petrie, Flinders. Memphis II, 1909, p. 2.

2. Petrie, Flinders. Memphis II, 1909, p. 1.

3. Petrie, Flinders. Memphis III, 1910, p. 40.

4. Petrie, Flinders. Memphis II, 1909, p. 4.

5. Aime-Giron, Noel. ANNALES DU SERVICE DES ANTIQUITES DE L’EGYPTE, Imprimerie De L’institut Francais D’Archeologie Orientale, published in Egypt, 1940, Volume XL, pp. 453-454.

6. Jeremiah 43:12-13.

We found the “great stones” of Jeremiah 43:9! An archaeologist has told me that his colleagues would raise the following objections to this find. He said they would want a “specialist in history” and the “skill of a fieldwork archaeologist”. I sought help from other archaeologists during this search and believe this was shown by what was recorded in our book "Great Stones". And I have quoted those who were experts in these fields. I was told, “There needs to be full comparative analysis of the frequency of discovery of raw materials of hard-stone production at a palatial site of this period.” As for a palatial site of this period, there is Tell Defenneh and the 26th Dynasty palace there, and Mr. Petrie looked for raw materials of stone buried out front of that palace, but did not find any. Also, “Perhaps the most important area, with real new prospects, is the interpretation and dating of levels at the site.” The site (the berms at the entrance of the palace of Apries, where the stones were found) did have dated artifacts that were buried there. And these date from 12th Dynasty sculptured blocks to the bronze corner of a door with the name of a pharaoh of the 26th Dynasty, the dynasty when the prophet Jeremiah was there. But I have a question, why is all this necessary? One is tempted to ask why these things were not required of Mr. Flinders Petrie. But now, because of those who were associated with these stones, the prophet Jeremiah and King Nebuchadnezzar, more is required? Why saddle yourself with all this? For in the end none of it would be accepted as proof. Even if I could afford a “specialist in history”, and “full comparative analysis”, etc., when all is done this still would not be accepted as validation that these two stones are the ones of Jeremiah 43:9.

But we were successful and I held both of these “great” stones in one “hand” as it says in Jeremiah 43:9. Everyone thought these stones that Jeremiah buried were some large rocks because they were called “great” stones. The Hebrew word “great” means “great in any sense,” (Strong’s, 1890, #1419). As in English, when we say Alexander the Great, who was not tall but an important person in history. Only the context of the passage of scripture will determine if it refers to size, something important or valuable. They had to be something more than normal stones. Remember it was to be a sign, and to bury rocks, whether small or large, that could be found most anywhere is not a sign. And these “great stones” were found in the bricked area right in front of the entry of the palace of Apries. Which I view as another confirmation that Memphis is Tahpanhes. “Take great stones in thine hand, and hide them in the clay in the brickkiln, which is at the entry of Pharaoh's house in Tahpanhes,” (Jeremiah 43:9). Please read about this for free in our book GREAT STONES Jeremiah 43:9, go to the above button “GREAT STONES”, and then move down to CHAPTERS 1-16 and click on it.

http://www.truechristianshortstoriesfreebygmmatheny.com/chapters-1-16.html

I give praise to my Lord and Savior Jesus Christ.

Nancy and I went to Oxford, England, where we spent parts of four days, January 9-12, 2008. I put in for translation the Phoenician letter about “all the gods of Tahpanhes”, which includes about 30 pages of notes. I especially wanted this complete Phoenician letter because I hoped it might have more to it and even possibly help identify the site. (It did!) This letter was found at Memphis not Tell Defenneh. This in itself does not prove that Memphis was Tahpanhes but does give Memphis a 50/50 chance. This will be brought up again in more detail, but for now the only point I am making is that it has been proven that either the person who wrote the letter or the one who received the letter had to be living there and worshiping all these “gods of Tahpanhes”. Memphis therefore would qualify, not only because of her size and her nineteen temples, but also because the only place in Egypt where the name Tahpanhes has ever been found was at Memphis. (This letter was written in Aramaic and is why they will say the name Tahpanhes has never been found in Egyptian “hieroglyphics”.)

The Phoenician letter. In January, 1940, Mr. Noel Aime-Giron began the study of the then newly found letter about “Baal Saphon and all the gods of Tahpanhes”. This letter had been found at Saqqara (the necropolis of Memphis). Mr. Aime-Giron made the translation and comments that will follow. But before we get to these, I want to quickly go over a couple of other things he brought up in his article.5 Not only is it believed that Tell Defenneh is Tahpanhes of the Bible but some scholars believe it is also “Baal-zephon” of Exodus 14:2. And this is believed because of the article by Mr. Aime-Giron. His theory is based on two things. First, he believes that because Baal-zaphon was the only god whose name is given in the Phoenician letter, that therefore he was the main god and thus the *city took its name from this deity. Of course, this is all based on the supposition that Tell Defenneh was Tahpanhes. But those who worshiped Baal-zaphon also identified it with Ptah6 the main god of Memphis. So it would fit to have Baal-Zaphon being the main god of Memphis. However it is logical to believe that the reason Baal-zaphon is mentioned in the letter was because the person who wrote this letter and the one to whom it was addressed, according to Mr. Aime-Giron,7 were both Phoenicians. And this god was the main god in their home country of Phoenicia, so they would naturally mention it before others.

*(I do not believe the Baal-Zephon of the Red Sea crossing, was at the site of Memphis or any city. The Jews consistently make Baal-Zephon and idol, or a place with an idol and its temple. Josephus did not say that Baal-zephon was a city, but only called it a “place.” “[O]n the third day they came to a place called Beelzephon….” [Josephus. Antiquities, II, 15, 1]. Other Jewish sources say that Baal-zephon was an idol: “before the idol Zephon” [Targum Jonathan also Targum Onkelos, both 3rd century AD]. Legends of the Jews said that Pharaoh “hastened to offer sacrifices to him [Baalzephon, where]...the great sanctuary of Baal-zephon was situated.” “Of set purpose God had left Baalzephon uninjured, alone of all the Egyptian idols. He wanted the Egyptian people to think that this idol was possessed of exceeding might, which it exercised to prevent the Israelites from journeying on” (Legends of the Jews, III, Pharaoh Pursues the Hebrews; also Targum Jonathan, Exodus XIV.)

Secondly, Mr. Aime-Giron cites a stela8 in the Cairo Museum that has the god of Baal on it and was said to have come from Tell Defenneh. Whatever else might be said about this stela, it is, at the least, interesting in that it has this foreign deity of Baal on it mixed with hieroglyphics and Egyptian symbols. But it is less than convincing that this stela ever came from Tell Defenneh. Mr. Noel Aime-Giron said that, “The Journal of Entry of the Gizeh Museum, recorded it [the stela], by mentioning: ‘Alexandria, July 1881, purchased.’” Then in the “Notice of the principal monuments shown in the Gizeh Museum, published in 1897 by Grebault (nr. 438)...its origin is given as Lower Egypt. It is only in 1906, in his Egyptological Researches, that Max Muller. added: ‘I can add to it that after a communication from the obliging conservator, Mr. G. Daressy, the stone has been found at a highly interesting place, at Tell- Defen.’”9 The museum originally said it was purchased at “Alexandria, July 1881,” apparently by some merchant of antiquities, then in 1897 we are told it came from “lower Egypt”, which has dozens of cities and would include both Alexandria and Tell Defenneh, then nine years later in 1906, we are told it came from Tell Defenneh. Well, maybe yes and maybe no. It would have been helpful if Mr. Daressy had said how the information came to him, but it is not given. For the sake of the argument it is at least a possibility this stela came from Tell Defenneh, but I do not see this proving the main god there was Baal. I quoted Mr. Flinders Petrie who said the main group of people there were Greeks10 and Baal-zaphon was not one of their deities. I do not doubt the possibility of this god being worshiped there by someone who was Phoenician, but certainly it was not the main deity. When Mr. Petrie excavated the site of Tell Defenneh, he did find artifacts of different Egyptian gods such as Ptah, Sokar, Isis, and Horus,11 but Mr. Petrie did not find Baal-zaphon or any other Baal at Tell Defenneh.

Paleography. As to the Phoenician letter, Mr. Giron said some interesting things in a section he entitles “Paleography and the age of the Document.” The studying and deciphering of ancient writings is an amazing science, leaving you with the impression that we can know more about the letter than the person who received it. And all this is done through the eye of the microscope that looks back in time some 2600 years. I will give a brief part of his comments found in his article12 along with the actual letter itself and will then comment on it.

After he discusses the script used in the letter, he concludes that it was written about the time of “the epoch of Amasis.” Amasis was a Pharaoh of the 26th Dynasty and ruled Egypt from 570 to 526 B.C. This letter was a private letter between two sisters. The one sister “Bas’u” (who he believed was living at Tahpanhes) had sent a letter to her sister “Arisuth” who was living at Memphis. Bas’u acknowledges having received some funds from her sister, Arisuth, which she used to meet some legal obligation. Unfortunately, after 2,600 years some of the letters and words have “fallen off,” and this is shown by a blank space ____ or are no longer readable and he has marked the space where the word would have been with “?”.

The outside or back of the letter: “To Arisuth daughter of Esmunyaton”

The inside of the letter: “I tell my sister Arisuth, your sister Bas’u says: Since you are in good health and me too, you return your blessings to Ba’al Saphon and to all the gods of Tahpanhes so that they keep you in good health. The money that you sent me arrived; that produced me weight (in sequels) 3˝ 1/6 (?) (one more) q(uart)? ____ ____ ____. I lavished in addition (?) all the money that belonged to me more of yours (?) and I gave it to _____ have confidence in ____ that I know in this ____. You sent me the acquittal manuscript (?) I will pay it to his ____.”

The letter is less than impressive, but his commentary on this letter is enlightening.

“This white space [blank space on the outside of the letter] had to be used for the seal, and the tear of the papyrus just after the word [he gives the original script] seems to have occurred when the envelope was opened…It seems even that small fragments of virgin wax [the seal] still adhere, here and there, on the front of the document where they would have remained attached after the pleat opening by the addressee…The fifth line and the address on the back, on the contrary, makes you understand that she used a worn tool and betrays a certain haste, confirmed by the absence of the points of separation. One has the impression that the sender wrote these last ones [lines] with a reed near at hand at the moment of giving her letter to the messenger, and maybe even outside of her place [house]. The ink tracks, on the left corner of the bottom margin, confirm this diagnosis: they are in fact copies [stains] of the two last signs of line four and prove that the document was folded while the ink was still fresh at this point.”