The Quest for Mount Sinai

By GM Matheny

It is necessary to read The Quest for the Red Sea Crossing FIRST, or you will be at a loss as to why Israel started where they did.

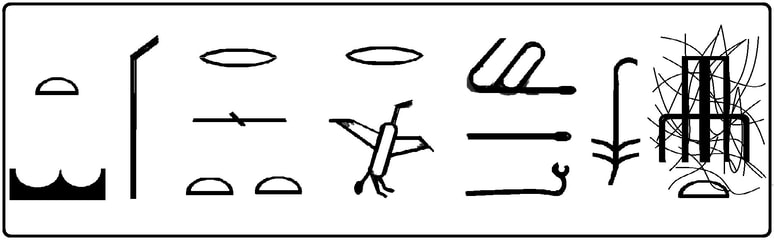

A pharaoh of Egypt went to Mount Sinai and engraved his named there!

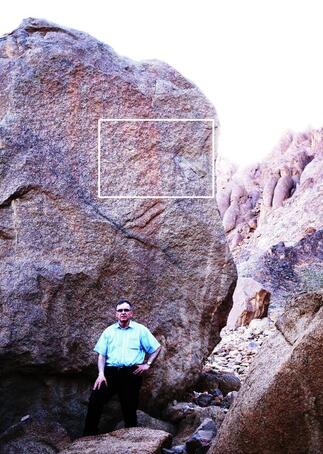

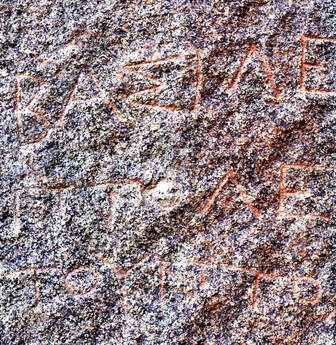

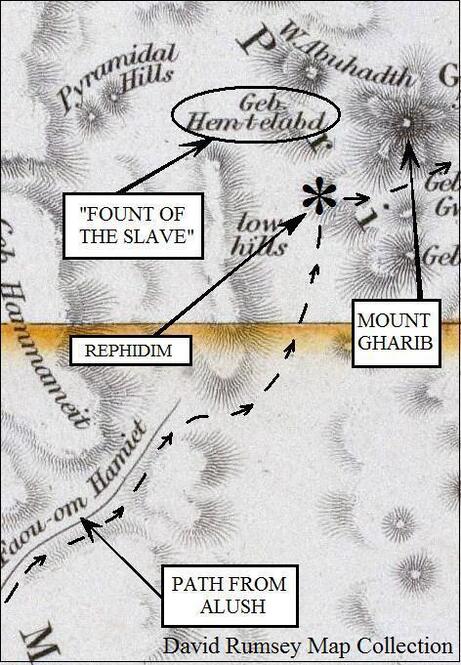

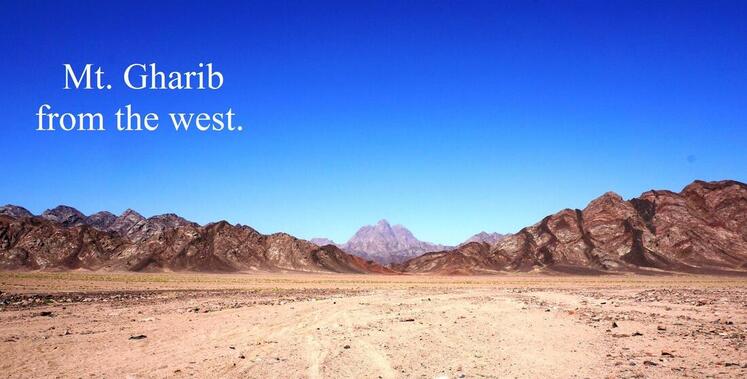

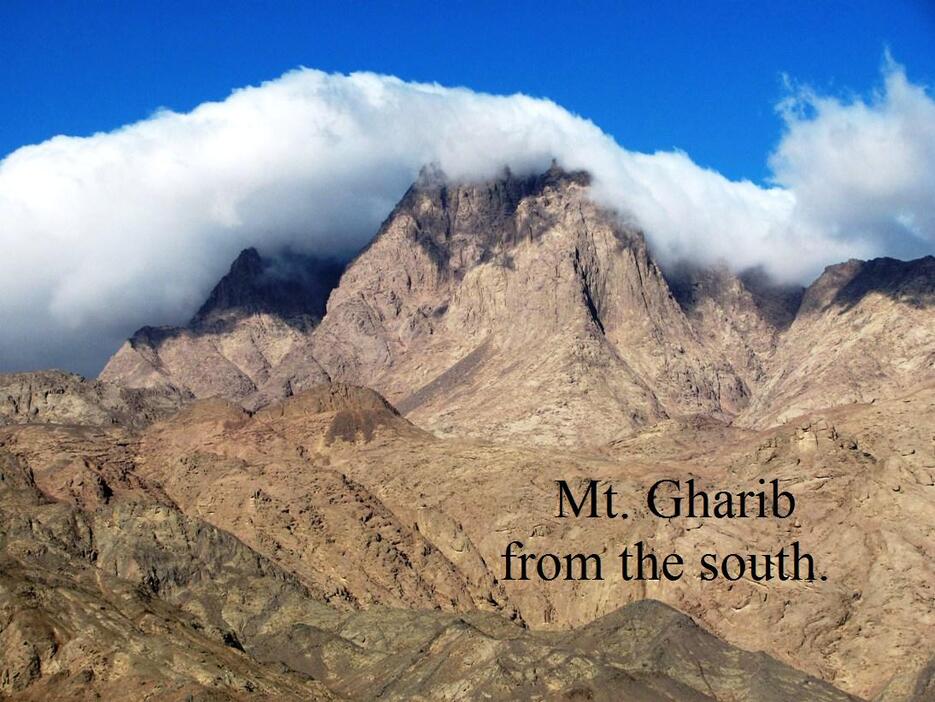

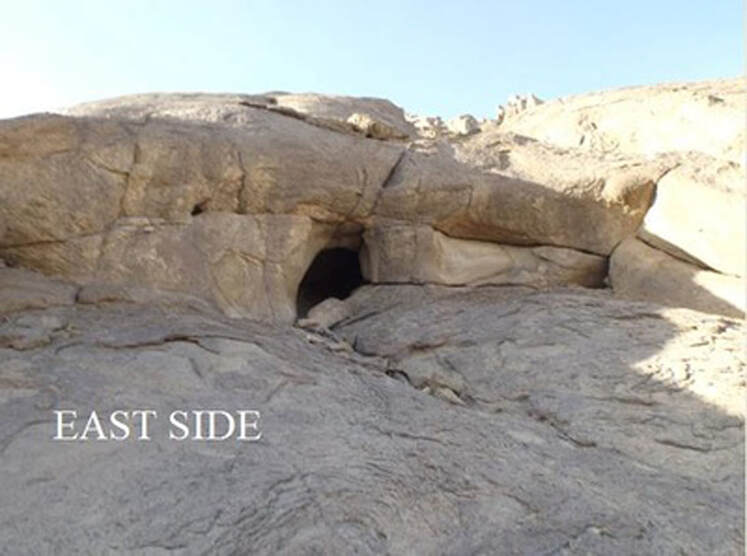

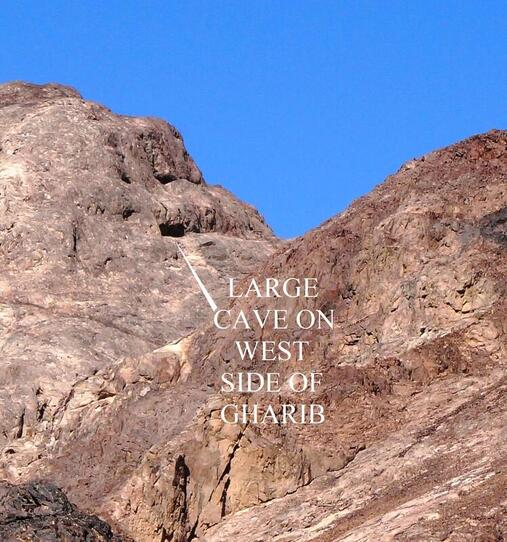

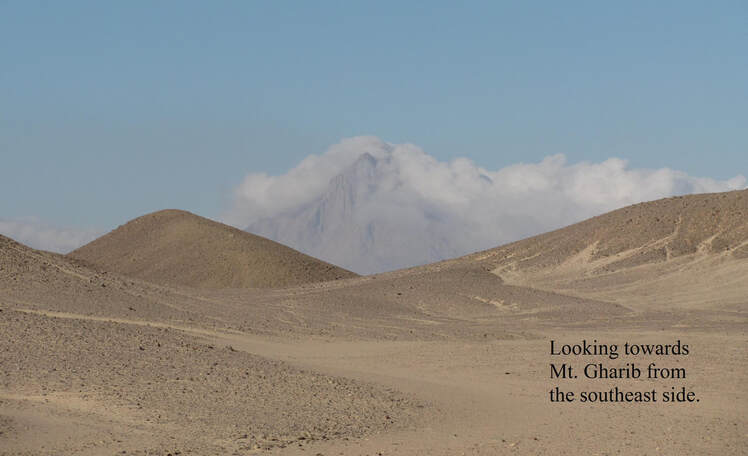

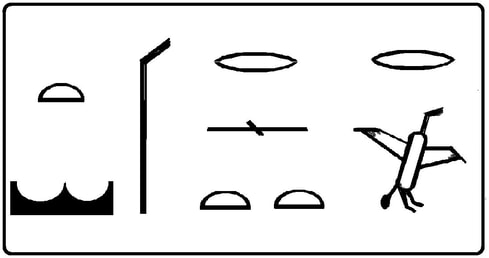

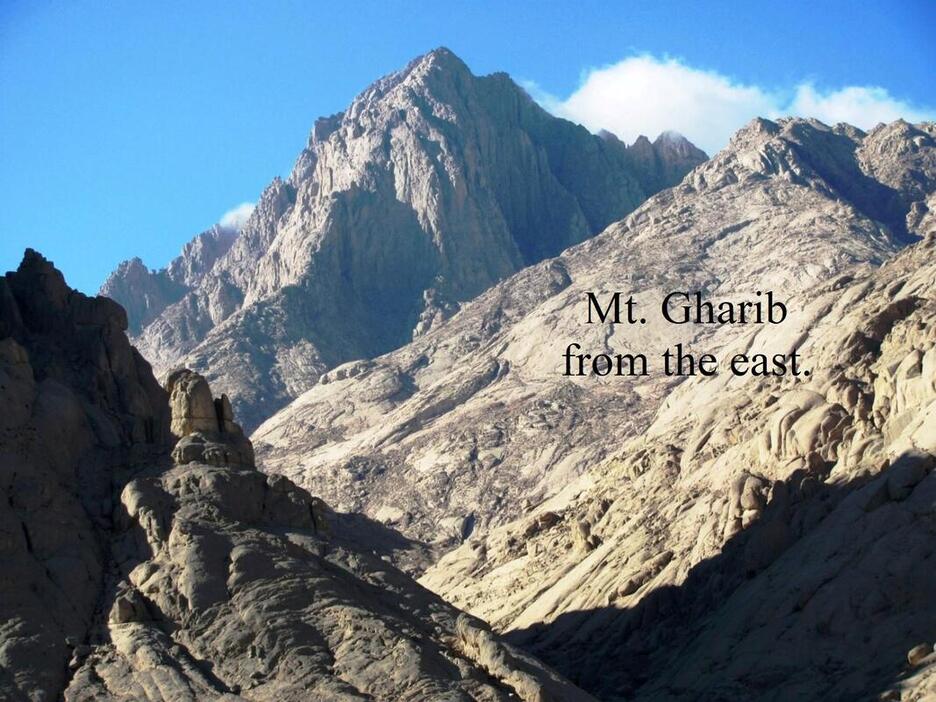

In December 2013, an inscription made by a King of Egypt was found at Mount Gharib, which I have proposed as Mount Sinai. And more than a hundred years ago, a hieroglyphic inscription was found in the East Nile Delta, also made by a king of Egypt, describing an expedition to a location the scholars have hotly debated. But the location is now confirmed, for the same king made both inscriptions, and he found something there that only Israel could have left.

This book can also be bought on Amazon.com

https://www.amazon.com/dp/B07DBF8TYV.

Both paperback and eBook.

(The footnotes in here will appear as large numbers.)

By GM Matheny

It is necessary to read The Quest for the Red Sea Crossing FIRST, or you will be at a loss as to why Israel started where they did.

A pharaoh of Egypt went to Mount Sinai and engraved his named there!

In December 2013, an inscription made by a King of Egypt was found at Mount Gharib, which I have proposed as Mount Sinai. And more than a hundred years ago, a hieroglyphic inscription was found in the East Nile Delta, also made by a king of Egypt, describing an expedition to a location the scholars have hotly debated. But the location is now confirmed, for the same king made both inscriptions, and he found something there that only Israel could have left.

This book can also be bought on Amazon.com

https://www.amazon.com/dp/B07DBF8TYV.

Both paperback and eBook.

(The footnotes in here will appear as large numbers.)

In December 2013, an inscription made by a King of Egypt was found at Mount Gharib, which I have proposed as Mount Sinai. And more than a hundred years ago, a hieroglyphic inscription was found in the East Nile Delta, also made by a king of Egypt, describing an expedition to a location the scholars have hotly debated. But the location is now confirmed, for the same king made both inscriptions, and he found something there that only Israel could have left.

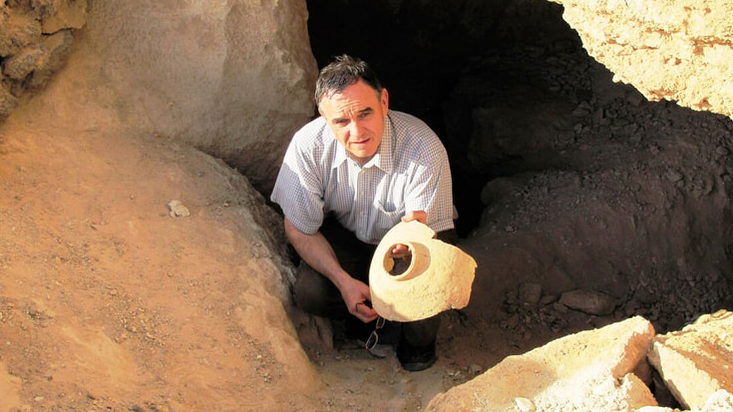

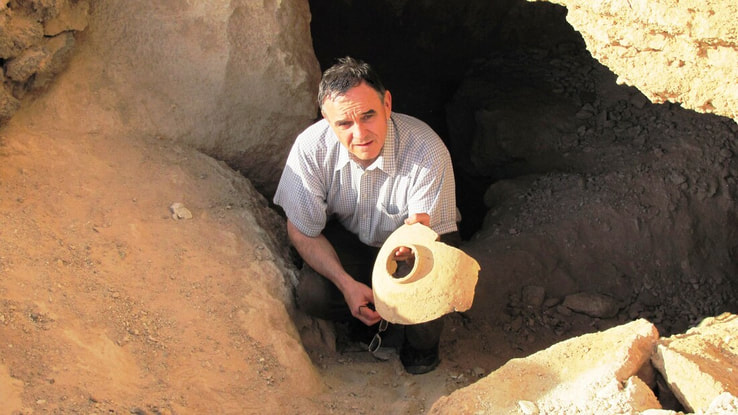

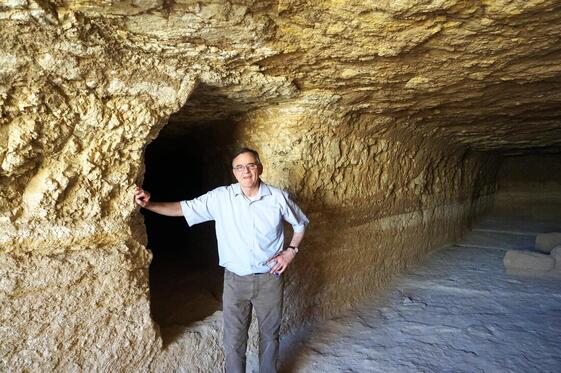

Author and wife Nancy

GM Matheny was a navy diver on the nuclear submarine USS Halibut SSGN-587 and received the Legion of Merit for a special operation. He is a graduate of Pacific Coast Baptist Bible College, 1979. He and his wife, Nancy, and their six children, arrived in Romania in 1991, where they serve as missionaries. He authored the books The Quest for the Great Stones of the Prophet Jeremiah, The Quest for Red Sea Crossing and GOD & SPIES: Recently Declassified Top Secret Operation

The Quest for Mount Sinai

Today there are nine different locations for Israel’s Red Sea crossing and more than twenty mountains that claim the title of Mount Sinai. One would think that after two hundred years of archaeology, we would have narrowed it down to a few choices; instead, now there is a growing number of opinions for the route of the Exodus and where the location of Mount Sinai was. What is wrong?

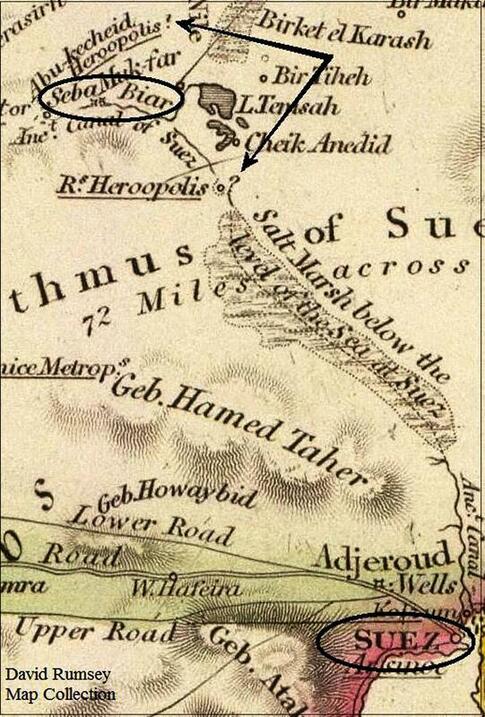

Almost everyone is starting the Exodus from the east side of the Nile Delta. And therefore must have the sea crossing east of that, either at the Bitter lakes, Gulf of Suez, or Gulf of Aqaba. This is also why they are not looking in the Eastern Desert of Egypt for Mount Sinai. Because if the Israelites crossed the sea at either one of these areas (Isthmus or Gulf of Aqaba), then they would not cross the sea again in order to reach the Eastern Desert.

This book was originally from the book EXODUS: The Route * Sea Crossing * God’s Mountain, published by XULON PRESS, but was separated into two books; The Quest for the Red Sea Crossing and The Quest for Mount Sinai, both by GM Matheny. To understand why Israel started her journeys in the area of Old Cairo, one will need to read our book The Quest for the Red Sea Crossing, https://www.amazon.com/dp/1982966114

But in short, both Josephus (1st century AD, Jewish historian) and Artapanus (3rd–2nd century BC, Jewish historian) have Israel starting the Exodus on the west side of the Nile. Israel would have crossed the flooded Nile and as such all four of the place names as given in Exodus 14:2 (Pi-hahiroth, Migdol, Baal-zephon and the sea) can easily be found.

In December 2013, an inscription made by a King of Egypt was found at Mount Gharib, which I have proposed as Mount Sinai. And more than a hundred years ago, a hieroglyphic inscription was found in the East Nile Delta, also made by a king of Egypt, describing an expedition to a location the scholars have hotly debated. But the location is now confirmed, for the same king made both inscriptions, and he found something there that only Israel could have left.

Author and wife Nancy

GM Matheny was a navy diver on the nuclear submarine USS Halibut SSGN-587 and received the Legion of Merit for a special operation. He is a graduate of Pacific Coast Baptist Bible College, 1979. He and his wife, Nancy, and their six children, arrived in Romania in 1991, where they serve as missionaries. He authored the books The Quest for the Great Stones of the Prophet Jeremiah, The Quest for Red Sea Crossing and GOD & SPIES: Recently Declassified Top Secret Operation

The Quest for Mount Sinai

Today there are nine different locations for Israel’s Red Sea crossing and more than twenty mountains that claim the title of Mount Sinai. One would think that after two hundred years of archaeology, we would have narrowed it down to a few choices; instead, now there is a growing number of opinions for the route of the Exodus and where the location of Mount Sinai was. What is wrong?

Almost everyone is starting the Exodus from the east side of the Nile Delta. And therefore must have the sea crossing east of that, either at the Bitter lakes, Gulf of Suez, or Gulf of Aqaba. This is also why they are not looking in the Eastern Desert of Egypt for Mount Sinai. Because if the Israelites crossed the sea at either one of these areas (Isthmus or Gulf of Aqaba), then they would not cross the sea again in order to reach the Eastern Desert.

This book was originally from the book EXODUS: The Route * Sea Crossing * God’s Mountain, published by XULON PRESS, but was separated into two books; The Quest for the Red Sea Crossing and The Quest for Mount Sinai, both by GM Matheny. To understand why Israel started her journeys in the area of Old Cairo, one will need to read our book The Quest for the Red Sea Crossing, https://www.amazon.com/dp/1982966114

But in short, both Josephus (1st century AD, Jewish historian) and Artapanus (3rd–2nd century BC, Jewish historian) have Israel starting the Exodus on the west side of the Nile. Israel would have crossed the flooded Nile and as such all four of the place names as given in Exodus 14:2 (Pi-hahiroth, Migdol, Baal-zephon and the sea) can easily be found.

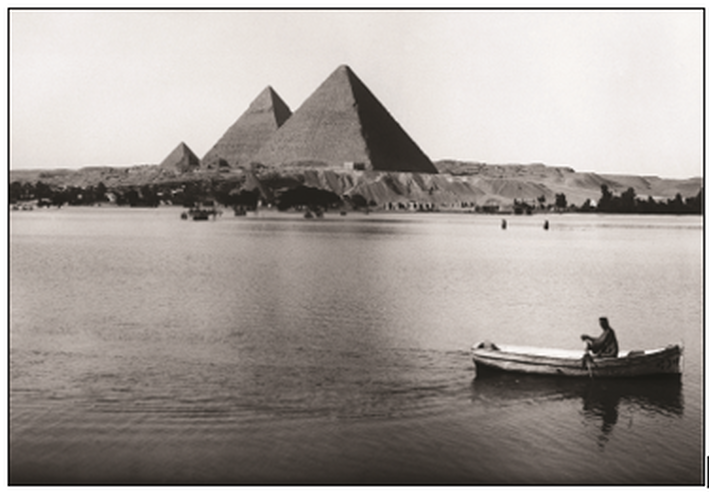

Annual flood before the Aswan Dam.

Photograph Giza Pyramids © October 31, 1927.

The above picture is used by permission,

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The annual inundation averaged twenty-four feet above the Nile with the flooded waters being six miles across from Cairo to the Great Pyramid. The Egyptians called this land the Land of Papyrus and when flooded the Sea of Papyrus, the equivalent of the Hebrew words “Yam Suf” which is translated Red Sea. The Quest for the Red Sea Crossing only teaches one sea crossing by Israel and in deep water not multiple sea crossings, or in shallow water as critics have said.

All rights reserved solely by the author, Copyright © 2014 by G.M. Matheny. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without the permission of the author. Scripture quotations are taken from The King James Bible (KJB). All quotations, whether from the Bible, archaeologists, or scholars, are italicized. Bold print or underlining used in verses or quotations of others reflects my emphasis. For the meaning of the Bible words in the original languages, I will be using Gesenius’ Lexicon and Strong’s Concordance, hereafter labeled Strong’s.

“And thou shalt remember all the way which the LORD thy God led thee these forty years in the wilderness, to humble thee, and to prove thee, to know what was in thine heart, whether thou wouldest keep his commandments, or no. And he humbled thee, and suffered thee to hunger, and fed thee with manna, which thou knewest not, neither did thy fathers know; that he might make thee know that man doth not live by bread only, but by every word that proceedeth out of the mouth of the LORD doth man live. Thy raiment waxed not old upon thee, neither did thy foot swell, these forty years. Thou shalt also consider in thine heart, that, as a man chasteneth his son, so the LORD thy God chasteneth thee” (Deuteronomy 8:2–5).

Table of Contents

Preface

The wanderings of Israel.

Chapter One

Mount Sinai was by the “country of the Troglodytes,” near where Moses stayed in Midian and in Arabia.

Chapter Two

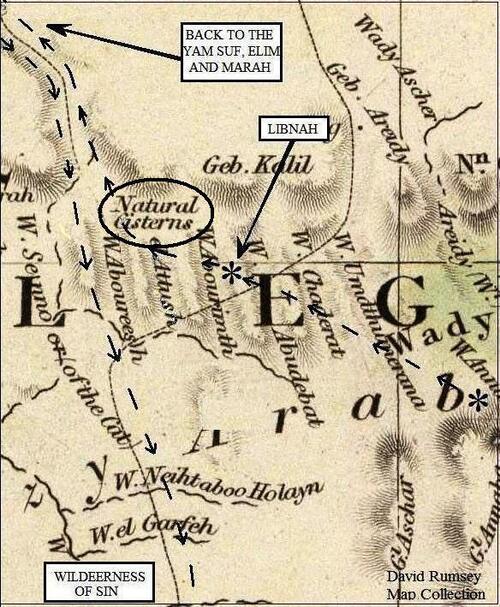

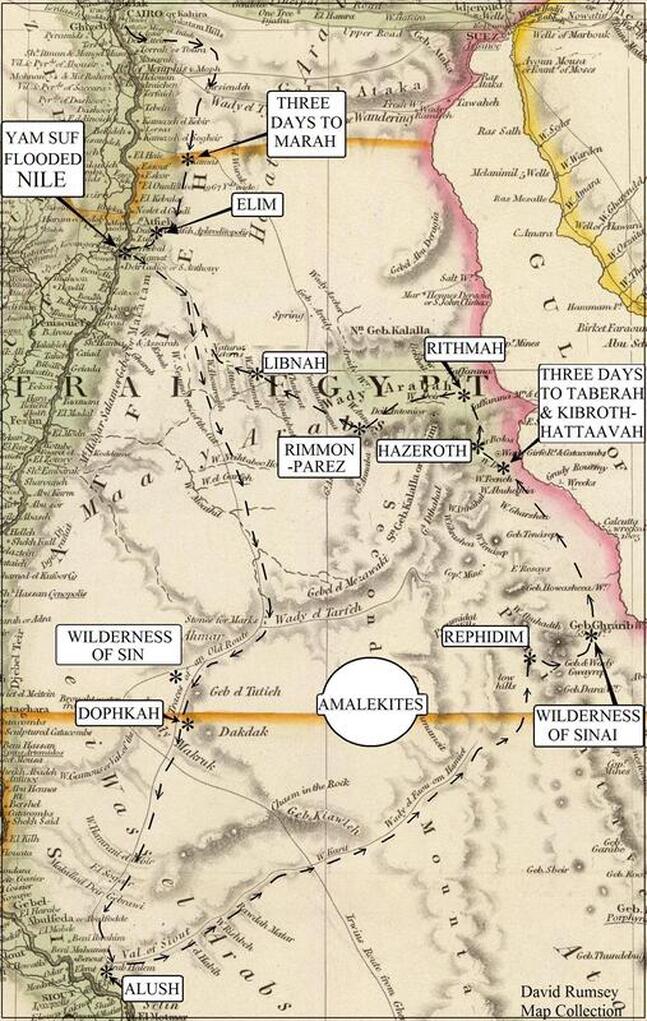

Encampments of Shur, Wilderness of Etham, Marah, Elim, Red Sea, Wilderness of Sin, Dophkah, Alush, and Rephidim.

Chapter Three

Encampments of Wilderness of Sinai, Taberah, Kibroth-hattaavah, Hazeroth,

Rithmah, Rimmon-parez, Libnah, and No. 17: Rissah.

Chapter Four

“Eleven days to Kadesh.”

Chapter Five

Encampments of Kadesh-barnea, Beersheba, Paran, Kehelathah, plus Mount Seir and the southwest border of Israel.

Chapter Six

The Mountain of God, Mount Sinai, Mount Horeb.

Photograph Giza Pyramids © October 31, 1927.

The above picture is used by permission,

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The annual inundation averaged twenty-four feet above the Nile with the flooded waters being six miles across from Cairo to the Great Pyramid. The Egyptians called this land the Land of Papyrus and when flooded the Sea of Papyrus, the equivalent of the Hebrew words “Yam Suf” which is translated Red Sea. The Quest for the Red Sea Crossing only teaches one sea crossing by Israel and in deep water not multiple sea crossings, or in shallow water as critics have said.

All rights reserved solely by the author, Copyright © 2014 by G.M. Matheny. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without the permission of the author. Scripture quotations are taken from The King James Bible (KJB). All quotations, whether from the Bible, archaeologists, or scholars, are italicized. Bold print or underlining used in verses or quotations of others reflects my emphasis. For the meaning of the Bible words in the original languages, I will be using Gesenius’ Lexicon and Strong’s Concordance, hereafter labeled Strong’s.

“And thou shalt remember all the way which the LORD thy God led thee these forty years in the wilderness, to humble thee, and to prove thee, to know what was in thine heart, whether thou wouldest keep his commandments, or no. And he humbled thee, and suffered thee to hunger, and fed thee with manna, which thou knewest not, neither did thy fathers know; that he might make thee know that man doth not live by bread only, but by every word that proceedeth out of the mouth of the LORD doth man live. Thy raiment waxed not old upon thee, neither did thy foot swell, these forty years. Thou shalt also consider in thine heart, that, as a man chasteneth his son, so the LORD thy God chasteneth thee” (Deuteronomy 8:2–5).

Table of Contents

Preface

The wanderings of Israel.

Chapter One

Mount Sinai was by the “country of the Troglodytes,” near where Moses stayed in Midian and in Arabia.

Chapter Two

Encampments of Shur, Wilderness of Etham, Marah, Elim, Red Sea, Wilderness of Sin, Dophkah, Alush, and Rephidim.

Chapter Three

Encampments of Wilderness of Sinai, Taberah, Kibroth-hattaavah, Hazeroth,

Rithmah, Rimmon-parez, Libnah, and No. 17: Rissah.

Chapter Four

“Eleven days to Kadesh.”

Chapter Five

Encampments of Kadesh-barnea, Beersheba, Paran, Kehelathah, plus Mount Seir and the southwest border of Israel.

Chapter Six

The Mountain of God, Mount Sinai, Mount Horeb.

Preface

The wanderings

of Israel.

Anyone not familiar with this subject will be surprised by how much debate there is about the Exodus and which route the children of Israel took. When I first realized this debate was raging, I thought, “What is the matter with these people? Surely they could have figured this out by now. Just look on the map!” And I reasoned, “All they have to do is find a few of the place names that are given in the Bible and then backtrack from Mount Sinai with the average distance traveled per day.” So, I got out my Sunday school map of the Sinai Peninsula and looked for Mount Sinai, but to my surprise, it had a question mark next to it. Scholars were not even sure where it was. Yes, I had a lot to learn.

Confirmation of sites. I believed these encampments could be found: “seek, and ye shall find,” and in most cases, I believe we were successful. Because I had to learn from scratch, I will explain those things that were new to me.

Which source can we trust? Reading today’s commentaries on the Bible can be helpful, but there are Bible commentaries (by Jewish historians) that are two thousand years old! A few were written by those who saw the temple service and would have had access to scrolls no longer available. I learned more from them than from reading modern commentaries. There are some things I would not have understood about the Exodus without these ancient writings!

The ancient writers do not always agree among themselves, just as the scholars of today obviously disagree, since there are nine different crossing locations for the sea and more than twenty mountains that claim the title Mount Sinai. Where history, archaeology, or traditions contradict each other, then the Bible will be the ultimate authority and judge of what is error or correct; it was, after all, the original source of the Exodus. There are times I will quote an ancient source knowing I could not possibly agree with all the legends or traditions written therein. On the other hand, I believe the Bible and I believe the miracles of the Bible--all of them! I believe the biblical account of the Exodus and I interpret it the same way I would interpret an account of an event recorded in a newspaper. I do not believe like the critics who say the Exodus was a “fabricated history” by Jewish priests to provide their people with a past. The Exodus and the miracles of the Bible all happened as stated (I Corinthians 10:1–11), and though one may make an allegory from them, the events are historical.

Thankfully, there are scholars who believe the Bible, but most do not, especially when it disagrees with their theories. Would you expect scholars who do not believe the Bible to find any evidence for the Exodus? How hard would they look for it? How much time and money would you spend looking for something you did not believe existed? They do not like their source of information coming from the Bible that teaches about God, creation, and miracles. Yet, they will readily cherish any papyrus they find in the sand of Egypt, whose author would have believed in Egyptian mythology and worshiped a multitude of Egyptian gods, half of which were animals! Some even inform us that we should not interpret the miracles of the Bible literally. But Christ and His apostles interpreted the miracles of the Hebrew Scriptures (Old Testament) literally (Noah and the flood, Lot and the fire and brimstone that rained down from heaven, etc. Luke 17:26–29). They like to tell you that Moses could not have written the Pentateuch (the first five books of the Bible), as the last page records his death. It is, however, understood that the scribes of that day would have finished this part of Deuteronomy (under Joshua’s supervision) and may have written down other portions during the life of Moses, though under his supervision. However, these same textual scholars will divide the Pentateuch into different parts (Jahwist text, Elohist text, Deuteronomist text, Priestly text, hence J, E, D, and P text), which they believe were written by different authors at different times and later combined, and all of them hundreds of years after the time of Moses and the Exodus. But these are imaginary works, and no ancient text has ever been found that backs this up. On the other hand, there are thousands of ancient Hebrew texts in scrolls or fragments, including from the Dead Sea Scrolls, all in the form of our present-day Bible! Christ attributes all the Pentateuch to the authorship of Moses (Mark 1:44, Mark 7:10, Mark 10:2–3, Luke 16:31, Luke 24:27 and 44, John 5:46, and many other verses).

If archaeologists believe the Exodus happened, they still are not in agreement as to when it took place. And when searching for evidence of the Exodus, they will look for artifacts from the time periods of MB (Middle Bronze Age) II “C” (1650–1550 BC), or LB (Late Bronze) Age I (1550–1400 BC), or LB II “A” (1400–1300 BC), or LB “B” (1300–1200 BC), etc. And unless one can show finds for their particular Bronze Age period, or their personal chronology, his theory will not be accepted but declared invalid. This might shake some at first, but one should not forget these “experts” do not agree among themselves!

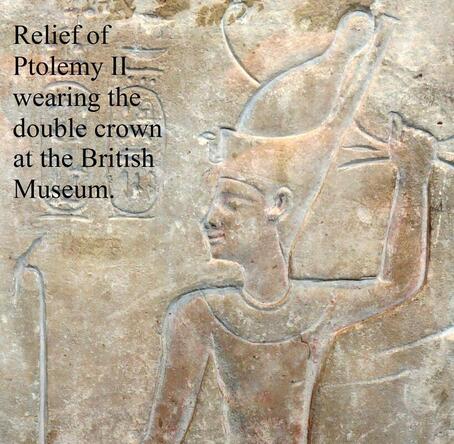

It is not the intent of this book to explain who the pharaoh was of the Exodus or the date it took place, though the ancients believed it was during the reign of Ahmose, the first king of the Eighteenth Dynasty. There are, however, reasons why this may not be so, explained later. Because the events of the Exodus took place three and a half millennia ago, I do not give “exact dates” that would be argued over, but I round off to the nearest decade or even the nearest century.

We are told Israel could not have survived in the desert. That it would have been difficult for such a multitude wandering the desert to have lived for more than a few weeks. Yes, and the same could be said about one person in the desert. They forget God, Who supplied water, meat (quail), and daily bread (Nehemiah 9:20). “Yea, forty years didst thou sustain them in the wilderness, so that they lacked nothing; their clothes waxed not old, and their feet swelled not” (Nehemiah 9:21). As others have brought out, the Israelites the critics are looking for never existed, because they do not believe God provided for His people, but the truth is, Israel “lacked nothing”!

The experts believe encampments of such a multitude would have left some sort of rubbish for them to track, but they are still trying to figure out which route the children of Israel followed. There was no thrown away, worn-out clothing, no piles of leftover manna (it melted Exodus 16:21), no broken pottery (discussed later), and no soda bottles or gum wrappers to follow.

The detractors’ inability to find the encampments of Israel is what they offer as proof! They only recently found (2002) the “workers village” for the pyramids of the Giza Plateau. It is estimated this town housed twenty thousand people and was built out of bricks, whereas the children of Israel lived in tents. And this discovery only came after archeologists had searched every inch of the Giza Plateau for the last two hundred years of archaeology.

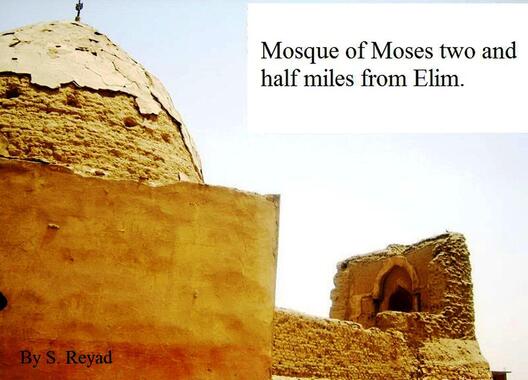

Traditions. Besides archaeology and history, there are traditions to consider. In truth, traditions are not the most trustworthy sources and may have been created simply to help out the local tourism industry. I once heard a certain city in Europe claimed to have “all seventeen graves” of the original twelve apostles! So though I was not looking for any signs that said “Moses slept here,” still, traditions are expected to have been passed down if one has the right route for the Exodus, and there are more traditions for this route than all the others put together!

A number of quotes in this book come from the book Legends of the Jews (compiled in 1909) and concern for the accuracy of such legends is understandable. This work was compiled by Louis Ginzberg, and in his preface he said, “In the present work, The Legends of the Jews, I have made the first attempt to gather from the original sources all Jewish legends, insofar as they refer to biblical personages and events, and reproduce them with the greatest attainable completeness and accuracy.” For original sources, he lists both Jewish and Christian writings.

Problems with place names. You may be surprised, as I was, by all the spelling differences among maps, even those of today. Sometimes, out in the middle of the desert, it depended on who pronounced the name, an Egyptian or a Bedouin. Sometimes, it was because of the Arabic language, which does not have certain letters that we have in our alphabet. There is no p in Arabic replaced with f and sometimes b, and no v replaced with b. Also, Arabic has some letters we do not have, which at first are hard to pronounce. Only a third of the letters in Arabic have a clear equivalent in our alphabet. Even when another language has the same sounds, one can still confuse the letters of s for z, or g for j; also, c, k, q, and g can get mixed up, and even t for d.

One can read books that will say if an Arabic place name has no meaning in the Arabic language, then it was transcribed from another language, which in the Eastern Desert would be from ancient Egyptian, Bedouin, or even the Midianite language. But this was not always the case, especially on older maps, which were made by French and German explorers who wrote down Arabic names as they sounded to them, leading to multiple spellings. You probably would not recognize your own name if someone from another country wrote it down as it sounded to him. British archaeologist Sir Wilkinson, who wrote down the names for the Eastern Desert, where the majority of the place names will be found, said, “I have kept in view, as much as possible, the English pronunciation, guiding my mode of spelling by the sound of a word, rather than by its Arabic orthography...now and then introduced a ‘p,’ which letter does not exist in Arabic, but which nevertheless comes near to the pronunciation in certain words.”1

I would like to add something here about the magnitude of the problem involved in finding these names that were written thirty-five hundred years ago in the Bible. First, there are at least eight languages in play, including ancient Egyptian, the Midianite language, and then the Greeks, who changed many names when they conquered Egypt. They were followed by the Romans, who gave many of the sites Latin names, then the Arabs, who conquered Egypt fourteen hundred years ago and gave hundreds of names in the Arabic language, and there are also some Bedouin names in the Eastern Desert of Egypt. Then, of course, we have Hebrew names from the Bible that we are reading in English. It is also possible there may be a few Turkish names from the Ottoman Empire.

The good news is that most of the place names on the Eastern Desert of Egypt are from one language, Arabic. The bad news is that on these older maps we will be using that 90 percent of these place names were transcribed into the Latin or the Roman alphabet, which we use in English. Though this helps us pronounce the names, it does not give us the meanings of the words. Translators do not like working with place names, but they especially do not like it when you cannot give them the original script of the language, in this case, the names written in Arabic. I claim no expertise on any of the original languages, but in most cases, even those who do would not help on this without the original script, and even when I did get the names in the original script, they could only explain the definitions of 10 percent or less of the place names. Even Sir Wilkinson only gave the meanings for a few names he wrote down. This was the single biggest problem I had!

The best help I found came from two Egyptian men, one who worked in a bank and the other a librarian, and both spoke English fluently. This will not be thought of as a “scientific method,” but Arabic was their own language and, more importantly, they lived in the Eastern Desert of Egypt and were already familiar with many of these names, an advantage that the other translators did not have. I also was able to confirm all of the place names they translated with ones I found on the Internet.

Neither the Egyptian hieroglyphics nor the Hebrew script used vowels when originally written, and in most cases, even the Arabic written today does not use vowels. Scholars say the vowel pointing for the Hebrew letters came during the Middle Ages and were added after these place names (and other words) were written. The Hebrews and the Egyptians, of course, did use vowels when speaking, but the placement of vowels in ancient Egyptian writings came later and is more conjecture than science. When it comes to the vowels, some translators will plainly tell you they are not sure, while others leave you with the impression they are fairly certain. Some translators will look to the Coptic or Greek languages, which did have vowels, to see how they spelled place names in Egypt. But those who recorded place names in Egypt did so often hundreds of years after the first time a site was named in hieroglyphics and cannot solve many of the problems. And so translators, when working with Egyptian hieroglyphics, will add vowels according to how they think the word would have been pronounced. This is another reason why it is possible to get a number of spellings for one word. For example, the Egyptian god, Atum, can be found with spellings of Tem, Temu, Tum, and Atem, but without the vowels it is just Tm.

The border of Egypt. When referring to countries or seas mentioned in the Bible, remember that the boundary lines on today’s maps are not the same as in the days of Moses. When you look at a map and view the Red Sea, Egypt, or Ethiopia, their locations are where they are today. We will have to look at the boundary lines as described in the Bible, not of those on a modern-day map. Secondly, when a site is located, if not in agreement, you will have to ask yourself the question, “Why?” Is it just because you have seen the site put on a map at a different location, or because the Bible places it there? You will have to be willing to look at the evidence that is brought forth. On my part, there were sites I had real problems with at first, when considering their new locations. Not because the Bible placed them where I had been taught, but because sites and boundaries had been dictated by tradition and repetition, so much so it was hard to imagine them being in any other location.

Some of the modern paintings of Christ are not those of a first-century Jew. Christ was a Jew by His mother, not the long, blond-haired, blue-eyed Anglo-Saxon that some have imagined. If the reader is not open to looking at God’s Word and the ancient Jewish sources (that place things in different locations), then some things will be forced and he will be looking in the wrong places. I believe the biggest hindrance to accepting this route, and therefore the location of Mount Sinai, will not be because of a lack of evidence, but fighting the traditional “Anglo-Saxon” diagram some have imagined was the route of the Exodus.

Should history and archaeology be important to Christians? I do believe we should put the focus on studying the theology of the Bible, but there is an incredible amount of information in the Hebrew Scriptures about Egypt and the cities there, and it was given by God! In truth, there are things that are “weightier matters,” as Christ said in reference to the weightier matters of the Law of God, but we should not ignore the other things in the Scriptures, “these ought ye to have done, and not to leave the other undone” (Matthew: 23:23). The history and archaeology of the Bible should not be explained by the scholars who do not believe in the supernatural and then sell their books to our young people, who are left with the impression the Bible is not trustworthy.

Some pretend it does not matter if one who writes about the Bible believes in miracles, the creation account, the resurrection, or even God, but this would be as naive as to believe that opposing political parties are unbiased when explaining each other’s views. Any researcher should at least study the Book that claims to be God’s Word and books written by those who believe in it. It only takes one small light at an exit door to show the way out of unbelief and error.

It is my sincere hope that, even with my limitations in this subject, God will be honored and His Name lifted up. “But there is a God in heaven that revealeth secrets…” (Daniel 2:28). I gladly, therefore, give Him credit for all that is right in this book, but like anyone, I certainly could have made mistakes (hopefully only small ones). There are, however, some things in this book, many things, which I have not read anywhere else on this subject.

What good will it do? I suppose someone could have asked that when Moses first brought the Ten Commandments down off Mt. Sinai, and three thousand people died because of their idolatry (Exodus 32:28).

The Bible says, “If they hear not Moses and the prophets, neither will they be persuaded, though one rose from the dead” (Luke 16:31). Some believe it is a waste of time to show people evidence to get them to believe, for if they believe not the Bible (“Moses and the prophets”), even if someone rose from the dead, they would not believe. This application was not meant for everyone. Lazarus rose from the dead, and “many of the Jews went away, and believed on Jesus” (John 12:9-11). God is not obligated to do this, nor is He our personal magician to work miracles for us at our will. But when He wants, there are times when He will do things such as the resurrection of Lazarus or smaller things to help the unbelief of some. And it is true that if someone does not want to believe, he will not, even if God works a miracle. We are told not to cast our “pearls before swine.” The chief priests did not believe when Lazarus was raised from the dead. Instead, they wanted to kill him (John 12:10). And it is more blessed to believe without seeing Lazarus or Christ raised from the dead, yet the Lord said, “Thomas, because thou hast seen me, thou hast believed…” (John 20:29). I am not teaching you should seek a sign (Matthew 12:39), nor do I know how many this would help, or for whom God would allow such. But the Apostle Paul would have never been saved by preaching alone. He had to be “knocked off his high horse” (Acts 9:3-6) before he would look up. With this said, what is wrong with trying to explain some things to people and giving them reasons to believe? The field of archaeology has been used by some to turn people away from the truth of God’s Word. There are books that will strengthen your faith, and there are books with “oppositions of science falsely so called” (I Timothy 6:20–21) that will take your faith away (I Timothy 6:20, Colossians 2:8). Many of the reasons I will give, come right out of the Bible, and these things were not written in vain, so hopefully, they will show how accurate God’s Word is.

My purpose is not to try and prove the Bible; it is true already. “All scripture is given by inspiration of God…” (II Timothy 3:16). Ultimately, faith comes from the Bible (Romans 10:17), not from artifacts buried in the sand. I looked for the route of the Exodus not to see if it was true, but because I already believed it was true.

“And the people came up out of Jordan on the tenth day of the first month, and encamped in Gilgal, in the east border of Jericho. And those twelve stones, which they took out of Jordan, did Joshua pitch in Gilgal. And he spake unto the children of Israel, saying, When your children shall ask their fathers in time to come, saying, What mean these stones? Then ye shall let your children know, saying, Israel came over this Jordan on dry land. For the LORD your God dried up the waters of Jordan from before you, until ye were passed over, as the LORD your God did to the Red sea, which he dried up from before us, until we were gone over: That all the people of the earth might know the hand of the LORD, that it is mighty: that ye might fear the LORD your God for ever” (Joshua 4:19–24).

It will be noticed that I am quoting from books that were published before 1923 (public domain). In a few cases, some were published after 1923, but their copyright was not renewed. In other cases, my quotes fall under “fair use” as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law, which says, “the reproduction of a particular work may be considered fair, such as criticism, comment…” My quotes of this type are all less than one sentence. It sounds as if it would be easy to get permission from others to quote their books, but not if they believe differently than you about the Exodus. Most of my requests to quote a source received no response. I am not saying this to complain, it is understandable. But I do not want the readers to think they are somehow missing out on the most up-to-date information. I, of course, read all the information I could find, both old and new, pro and con, and surprisingly, in most cases, the older works were more helpful and interesting, especially the ancient writings of the Jews and classical writers.

Miles Per Day

The encampments of the children of Israel are found in their proper order, with a reasonable distance traveled between them and an accessible route for their multitude.

How many miles a day could such a multitude have traveled with wagons (Numbers 7:3–8), children, the elderly, flocks, and all? For those who say Israel could not have traveled more than five or six miles a day because of the need to graze their herds and flocks, they need only look to the covered wagon trains and cattle drives of the western US. Wagon trains, unless hindered by forest, could travel twelve to sixteen miles a day. Cattle drives are said to have averaged fifteen miles a day or more, and their cattle actually gained weight at this pace. Their cattle grazed at noon and at night. Though it was not the norm, Barnes’ Notes on the Bible makes an interesting comment about miles per day from Genesis 31:20–24, saying it “would give him twelve days to travel three hundred English miles.” That would be twenty-five miles a day with children and herds. In truth, they (Jacob and his family) were fleeing from Laban, pushing themselves, but this shows that it was possible, and they sustained it for twelve days.

Western sheep cannot be compared to the sturdy Bedouin sheep of the Middle East. The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) website on Bedouin flocks, “Awassi sheep,” said, “flocks may be driven for as much as 35 km (21.75 miles) in 24 hours” (Williamson, 1949). http://www.fao.org/docrep/011/aj003e/AJ003E05.htm#fg21

The longest day’s march we have on the Exodus route is seventeen miles. The rate of fourteen miles a day was about the average on our route in the Eastern Desert of Egypt. There are, however, some scholars who want us to believe the average distance traveled was barely five miles a day, or that Israel traveled the absurd distance of sixty, seventy or more miles a day.

The children of Israel were prepared for this journey, being slaves used to hard work and rough living conditions, and at the start of their journey “there was not one feeble person among their tribes” (Psalms 105:37). In the same chapter, verse 39, it said the cloudy pillar that led them was as a “covering,” which would have given shade during the day on the hot desert and made it possible for them to travel at night. “And the LORD went before them by day in a pillar of a cloud, to lead them the way; and by night in a pillar of fire, to give them light; to go by day and night” (Exodus 13:21, Deuteronomy 1:33).

There are two variables in these miles-per-day averages. We do not know all the stops the Israelites made, nor do we know how long they stayed at each stop to rest. There are two times the Bible says Israel went three days, but only one stop is named (Exodus 15:22 and Numbers 10:33). They would have stopped each day, but no name is given for an encampment except the last one, probably because nothing exceptional happened at these stops or no name existed there. (In the desert, one would not expect to find a name at each location.) But this means there were most likely other stops not mentioned, and we learn that at the third place named after leaving Mount Sinai, forty days had gone by. Three days to get to Taberah (Numbers 10:33), thirty days of eating flesh at Kibroth-hattaavah (Numbers 11:19–20), and at least a week at Hazeroth, where Miriam (Numbers 12:15) had to wait outside the camp. My point is, they were able to rest sometimes between days of travel, which would make a big difference in how many miles a day they averaged. It should not be assumed, therefore, that it was only a one-day’s march between all the stations or that they only passed one night at each encampment.

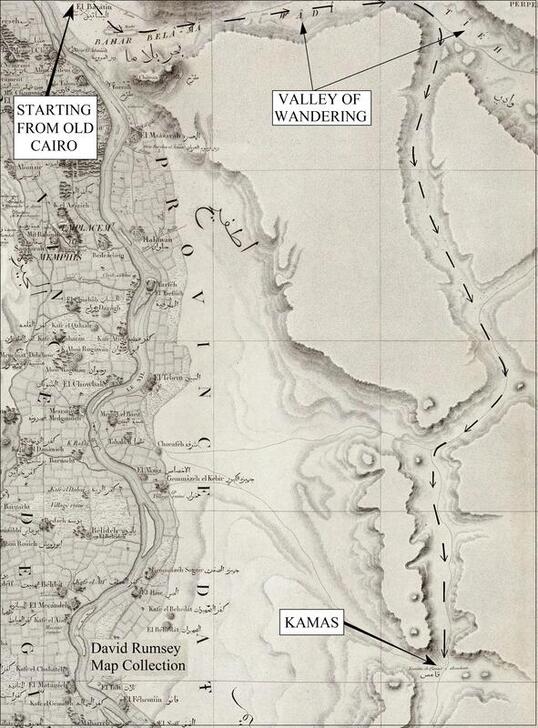

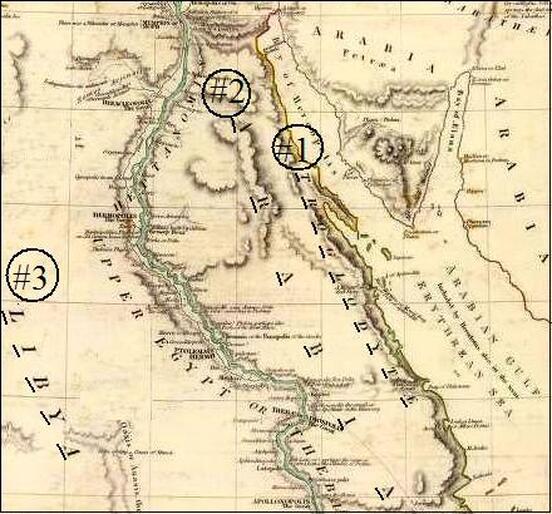

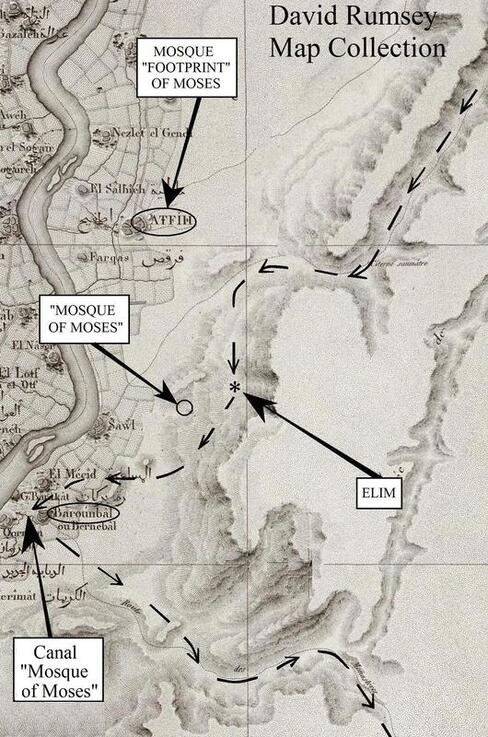

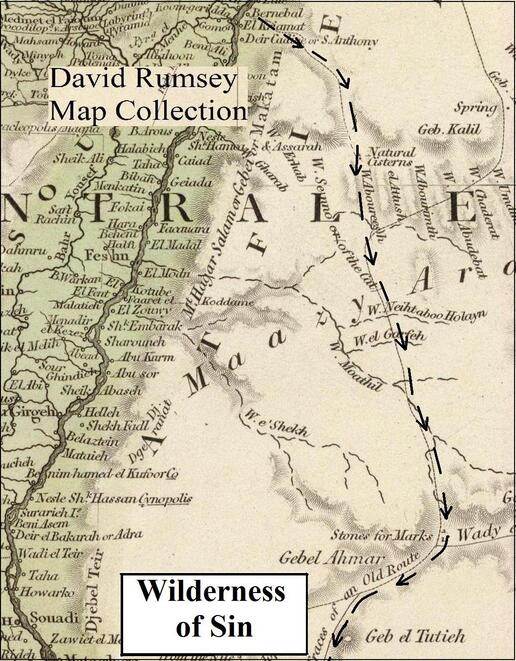

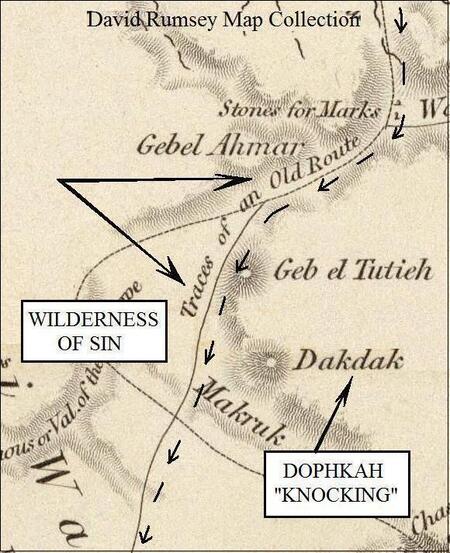

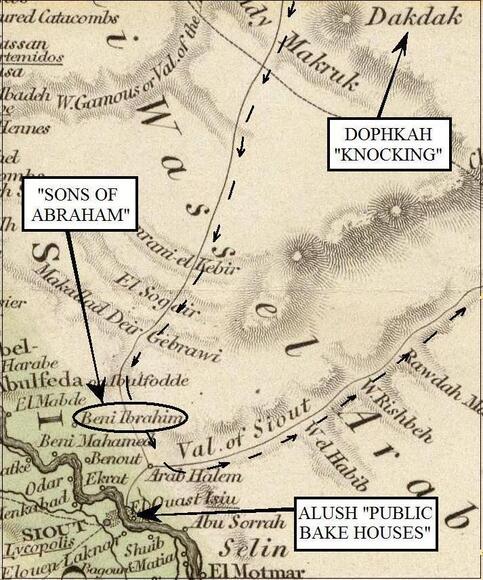

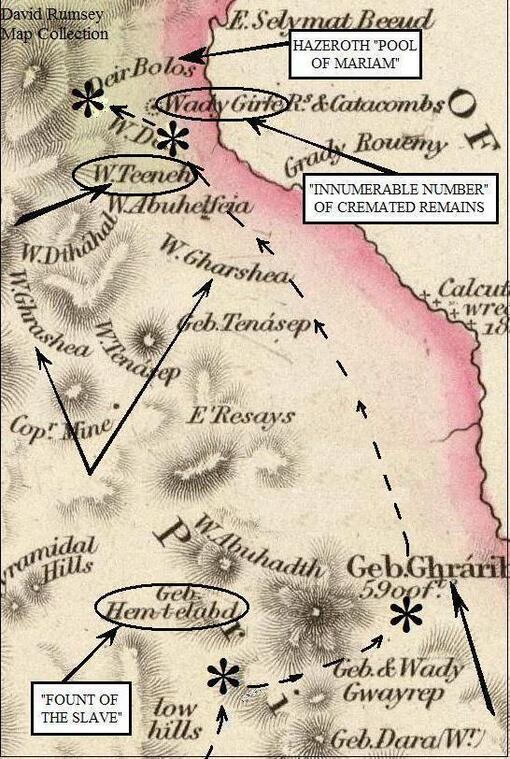

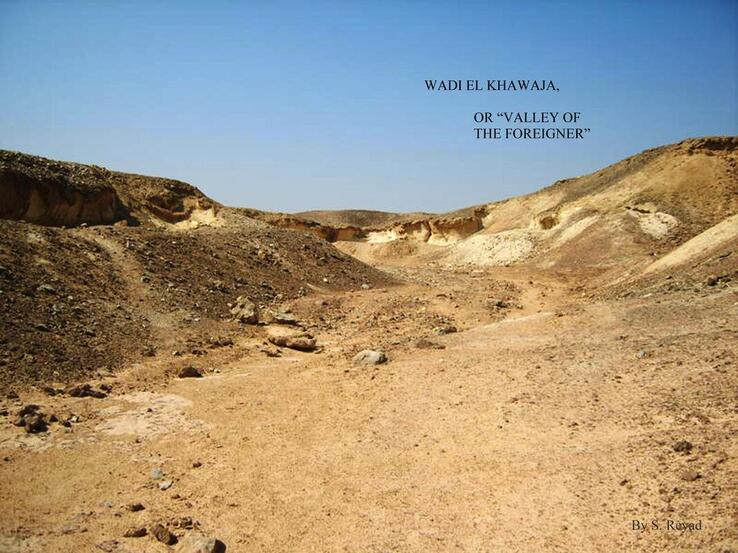

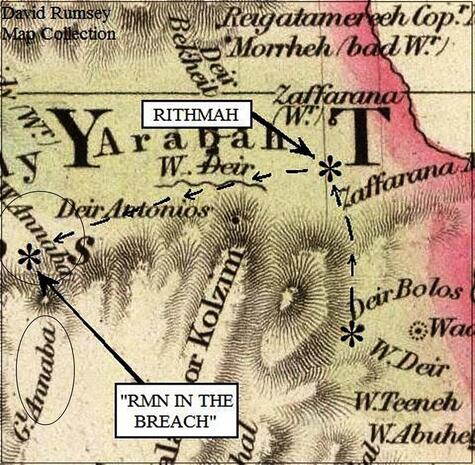

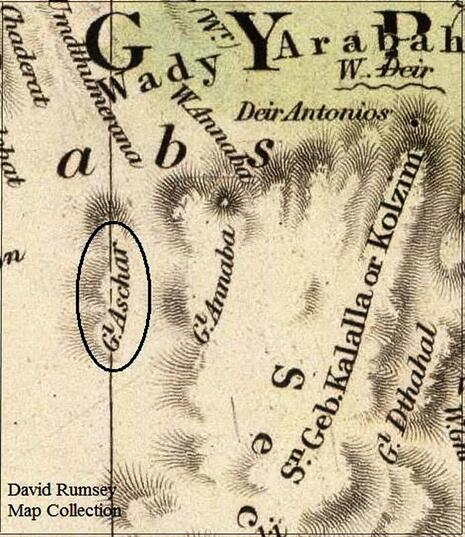

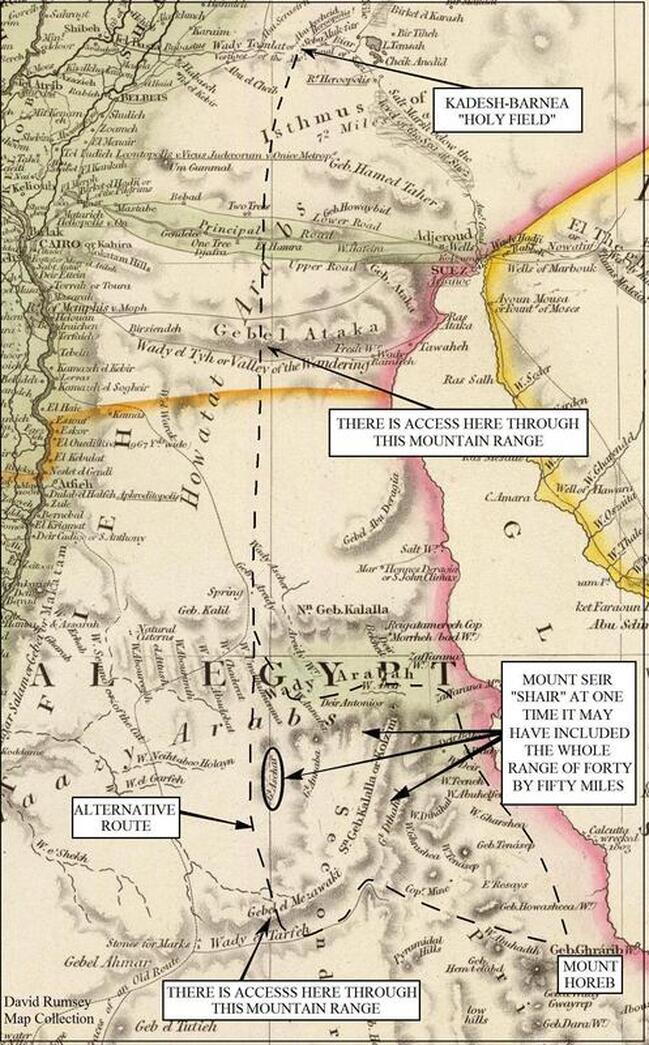

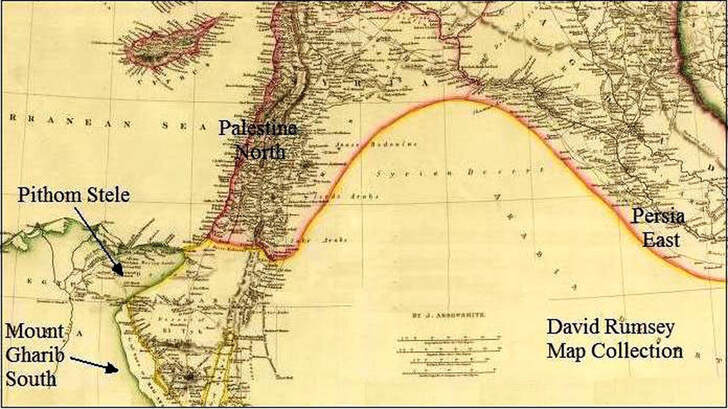

Maps. The primary map used is an 1844 map by John Arrowsmith, used by permission from the David Rumsey Map Collection, www.davidrumsey.com. I like this map, as it is easy to read and has most of the place names on it where Israel traveled. There are other maps, also from the David Rumsey Collection, which will be used because they show a better view of the landscape. The 1844 map received the place names for the Eastern Desert from Sir John Gardner Wilkinson.2 Sir Wilkinson made the original survey of the Eastern Desert and was the first to copy many of these names; I will, therefore, be using a number of his quotes.

It will be important to keep in mind the geography of Egypt. “Lower” Egypt is in the north, and “Upper” Egypt is in the south! The Nile flows from south to the north, the opposite of the Mississippi river; it is easy to forget this and become confused. As to pictures of burnt mountains, inscriptions, pillars, etc., these will be addressed later in this book. The first time I quote an ancient writer, besides giving his name, I will also give the approximate date he wrote and what his occupation was, but thereafter, unless helpful to the point being made, I may give only the name. Also, as much as possible, I wanted this work to be in the form of a story, not a phone book with only names and addresses, so though I believe it is well researched, it will not be all technical details.

ENDNOTES

1. John Murray. Sir John Gardner Wilkinson. A Handbook for Travelers in Egypt (1867), 42.

2. The 1844 map by John Arrowsmith has written on the Red Sea area the following: “The detail in the Egyptian Desert between Suez & Kenneh is copied from an original M.S. Drawing by J. Wilkinson, Esq.

The wanderings

of Israel.

Anyone not familiar with this subject will be surprised by how much debate there is about the Exodus and which route the children of Israel took. When I first realized this debate was raging, I thought, “What is the matter with these people? Surely they could have figured this out by now. Just look on the map!” And I reasoned, “All they have to do is find a few of the place names that are given in the Bible and then backtrack from Mount Sinai with the average distance traveled per day.” So, I got out my Sunday school map of the Sinai Peninsula and looked for Mount Sinai, but to my surprise, it had a question mark next to it. Scholars were not even sure where it was. Yes, I had a lot to learn.

Confirmation of sites. I believed these encampments could be found: “seek, and ye shall find,” and in most cases, I believe we were successful. Because I had to learn from scratch, I will explain those things that were new to me.

Which source can we trust? Reading today’s commentaries on the Bible can be helpful, but there are Bible commentaries (by Jewish historians) that are two thousand years old! A few were written by those who saw the temple service and would have had access to scrolls no longer available. I learned more from them than from reading modern commentaries. There are some things I would not have understood about the Exodus without these ancient writings!

The ancient writers do not always agree among themselves, just as the scholars of today obviously disagree, since there are nine different crossing locations for the sea and more than twenty mountains that claim the title Mount Sinai. Where history, archaeology, or traditions contradict each other, then the Bible will be the ultimate authority and judge of what is error or correct; it was, after all, the original source of the Exodus. There are times I will quote an ancient source knowing I could not possibly agree with all the legends or traditions written therein. On the other hand, I believe the Bible and I believe the miracles of the Bible--all of them! I believe the biblical account of the Exodus and I interpret it the same way I would interpret an account of an event recorded in a newspaper. I do not believe like the critics who say the Exodus was a “fabricated history” by Jewish priests to provide their people with a past. The Exodus and the miracles of the Bible all happened as stated (I Corinthians 10:1–11), and though one may make an allegory from them, the events are historical.

Thankfully, there are scholars who believe the Bible, but most do not, especially when it disagrees with their theories. Would you expect scholars who do not believe the Bible to find any evidence for the Exodus? How hard would they look for it? How much time and money would you spend looking for something you did not believe existed? They do not like their source of information coming from the Bible that teaches about God, creation, and miracles. Yet, they will readily cherish any papyrus they find in the sand of Egypt, whose author would have believed in Egyptian mythology and worshiped a multitude of Egyptian gods, half of which were animals! Some even inform us that we should not interpret the miracles of the Bible literally. But Christ and His apostles interpreted the miracles of the Hebrew Scriptures (Old Testament) literally (Noah and the flood, Lot and the fire and brimstone that rained down from heaven, etc. Luke 17:26–29). They like to tell you that Moses could not have written the Pentateuch (the first five books of the Bible), as the last page records his death. It is, however, understood that the scribes of that day would have finished this part of Deuteronomy (under Joshua’s supervision) and may have written down other portions during the life of Moses, though under his supervision. However, these same textual scholars will divide the Pentateuch into different parts (Jahwist text, Elohist text, Deuteronomist text, Priestly text, hence J, E, D, and P text), which they believe were written by different authors at different times and later combined, and all of them hundreds of years after the time of Moses and the Exodus. But these are imaginary works, and no ancient text has ever been found that backs this up. On the other hand, there are thousands of ancient Hebrew texts in scrolls or fragments, including from the Dead Sea Scrolls, all in the form of our present-day Bible! Christ attributes all the Pentateuch to the authorship of Moses (Mark 1:44, Mark 7:10, Mark 10:2–3, Luke 16:31, Luke 24:27 and 44, John 5:46, and many other verses).

If archaeologists believe the Exodus happened, they still are not in agreement as to when it took place. And when searching for evidence of the Exodus, they will look for artifacts from the time periods of MB (Middle Bronze Age) II “C” (1650–1550 BC), or LB (Late Bronze) Age I (1550–1400 BC), or LB II “A” (1400–1300 BC), or LB “B” (1300–1200 BC), etc. And unless one can show finds for their particular Bronze Age period, or their personal chronology, his theory will not be accepted but declared invalid. This might shake some at first, but one should not forget these “experts” do not agree among themselves!

It is not the intent of this book to explain who the pharaoh was of the Exodus or the date it took place, though the ancients believed it was during the reign of Ahmose, the first king of the Eighteenth Dynasty. There are, however, reasons why this may not be so, explained later. Because the events of the Exodus took place three and a half millennia ago, I do not give “exact dates” that would be argued over, but I round off to the nearest decade or even the nearest century.

We are told Israel could not have survived in the desert. That it would have been difficult for such a multitude wandering the desert to have lived for more than a few weeks. Yes, and the same could be said about one person in the desert. They forget God, Who supplied water, meat (quail), and daily bread (Nehemiah 9:20). “Yea, forty years didst thou sustain them in the wilderness, so that they lacked nothing; their clothes waxed not old, and their feet swelled not” (Nehemiah 9:21). As others have brought out, the Israelites the critics are looking for never existed, because they do not believe God provided for His people, but the truth is, Israel “lacked nothing”!

The experts believe encampments of such a multitude would have left some sort of rubbish for them to track, but they are still trying to figure out which route the children of Israel followed. There was no thrown away, worn-out clothing, no piles of leftover manna (it melted Exodus 16:21), no broken pottery (discussed later), and no soda bottles or gum wrappers to follow.

The detractors’ inability to find the encampments of Israel is what they offer as proof! They only recently found (2002) the “workers village” for the pyramids of the Giza Plateau. It is estimated this town housed twenty thousand people and was built out of bricks, whereas the children of Israel lived in tents. And this discovery only came after archeologists had searched every inch of the Giza Plateau for the last two hundred years of archaeology.

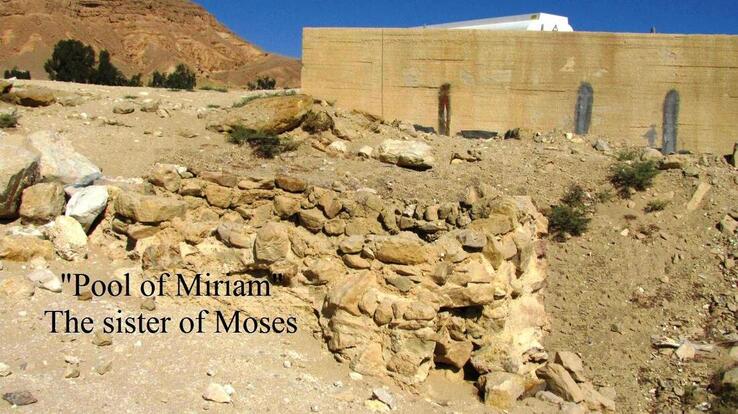

Traditions. Besides archaeology and history, there are traditions to consider. In truth, traditions are not the most trustworthy sources and may have been created simply to help out the local tourism industry. I once heard a certain city in Europe claimed to have “all seventeen graves” of the original twelve apostles! So though I was not looking for any signs that said “Moses slept here,” still, traditions are expected to have been passed down if one has the right route for the Exodus, and there are more traditions for this route than all the others put together!

A number of quotes in this book come from the book Legends of the Jews (compiled in 1909) and concern for the accuracy of such legends is understandable. This work was compiled by Louis Ginzberg, and in his preface he said, “In the present work, The Legends of the Jews, I have made the first attempt to gather from the original sources all Jewish legends, insofar as they refer to biblical personages and events, and reproduce them with the greatest attainable completeness and accuracy.” For original sources, he lists both Jewish and Christian writings.

Problems with place names. You may be surprised, as I was, by all the spelling differences among maps, even those of today. Sometimes, out in the middle of the desert, it depended on who pronounced the name, an Egyptian or a Bedouin. Sometimes, it was because of the Arabic language, which does not have certain letters that we have in our alphabet. There is no p in Arabic replaced with f and sometimes b, and no v replaced with b. Also, Arabic has some letters we do not have, which at first are hard to pronounce. Only a third of the letters in Arabic have a clear equivalent in our alphabet. Even when another language has the same sounds, one can still confuse the letters of s for z, or g for j; also, c, k, q, and g can get mixed up, and even t for d.

One can read books that will say if an Arabic place name has no meaning in the Arabic language, then it was transcribed from another language, which in the Eastern Desert would be from ancient Egyptian, Bedouin, or even the Midianite language. But this was not always the case, especially on older maps, which were made by French and German explorers who wrote down Arabic names as they sounded to them, leading to multiple spellings. You probably would not recognize your own name if someone from another country wrote it down as it sounded to him. British archaeologist Sir Wilkinson, who wrote down the names for the Eastern Desert, where the majority of the place names will be found, said, “I have kept in view, as much as possible, the English pronunciation, guiding my mode of spelling by the sound of a word, rather than by its Arabic orthography...now and then introduced a ‘p,’ which letter does not exist in Arabic, but which nevertheless comes near to the pronunciation in certain words.”1

I would like to add something here about the magnitude of the problem involved in finding these names that were written thirty-five hundred years ago in the Bible. First, there are at least eight languages in play, including ancient Egyptian, the Midianite language, and then the Greeks, who changed many names when they conquered Egypt. They were followed by the Romans, who gave many of the sites Latin names, then the Arabs, who conquered Egypt fourteen hundred years ago and gave hundreds of names in the Arabic language, and there are also some Bedouin names in the Eastern Desert of Egypt. Then, of course, we have Hebrew names from the Bible that we are reading in English. It is also possible there may be a few Turkish names from the Ottoman Empire.

The good news is that most of the place names on the Eastern Desert of Egypt are from one language, Arabic. The bad news is that on these older maps we will be using that 90 percent of these place names were transcribed into the Latin or the Roman alphabet, which we use in English. Though this helps us pronounce the names, it does not give us the meanings of the words. Translators do not like working with place names, but they especially do not like it when you cannot give them the original script of the language, in this case, the names written in Arabic. I claim no expertise on any of the original languages, but in most cases, even those who do would not help on this without the original script, and even when I did get the names in the original script, they could only explain the definitions of 10 percent or less of the place names. Even Sir Wilkinson only gave the meanings for a few names he wrote down. This was the single biggest problem I had!

The best help I found came from two Egyptian men, one who worked in a bank and the other a librarian, and both spoke English fluently. This will not be thought of as a “scientific method,” but Arabic was their own language and, more importantly, they lived in the Eastern Desert of Egypt and were already familiar with many of these names, an advantage that the other translators did not have. I also was able to confirm all of the place names they translated with ones I found on the Internet.

Neither the Egyptian hieroglyphics nor the Hebrew script used vowels when originally written, and in most cases, even the Arabic written today does not use vowels. Scholars say the vowel pointing for the Hebrew letters came during the Middle Ages and were added after these place names (and other words) were written. The Hebrews and the Egyptians, of course, did use vowels when speaking, but the placement of vowels in ancient Egyptian writings came later and is more conjecture than science. When it comes to the vowels, some translators will plainly tell you they are not sure, while others leave you with the impression they are fairly certain. Some translators will look to the Coptic or Greek languages, which did have vowels, to see how they spelled place names in Egypt. But those who recorded place names in Egypt did so often hundreds of years after the first time a site was named in hieroglyphics and cannot solve many of the problems. And so translators, when working with Egyptian hieroglyphics, will add vowels according to how they think the word would have been pronounced. This is another reason why it is possible to get a number of spellings for one word. For example, the Egyptian god, Atum, can be found with spellings of Tem, Temu, Tum, and Atem, but without the vowels it is just Tm.

The border of Egypt. When referring to countries or seas mentioned in the Bible, remember that the boundary lines on today’s maps are not the same as in the days of Moses. When you look at a map and view the Red Sea, Egypt, or Ethiopia, their locations are where they are today. We will have to look at the boundary lines as described in the Bible, not of those on a modern-day map. Secondly, when a site is located, if not in agreement, you will have to ask yourself the question, “Why?” Is it just because you have seen the site put on a map at a different location, or because the Bible places it there? You will have to be willing to look at the evidence that is brought forth. On my part, there were sites I had real problems with at first, when considering their new locations. Not because the Bible placed them where I had been taught, but because sites and boundaries had been dictated by tradition and repetition, so much so it was hard to imagine them being in any other location.

Some of the modern paintings of Christ are not those of a first-century Jew. Christ was a Jew by His mother, not the long, blond-haired, blue-eyed Anglo-Saxon that some have imagined. If the reader is not open to looking at God’s Word and the ancient Jewish sources (that place things in different locations), then some things will be forced and he will be looking in the wrong places. I believe the biggest hindrance to accepting this route, and therefore the location of Mount Sinai, will not be because of a lack of evidence, but fighting the traditional “Anglo-Saxon” diagram some have imagined was the route of the Exodus.

Should history and archaeology be important to Christians? I do believe we should put the focus on studying the theology of the Bible, but there is an incredible amount of information in the Hebrew Scriptures about Egypt and the cities there, and it was given by God! In truth, there are things that are “weightier matters,” as Christ said in reference to the weightier matters of the Law of God, but we should not ignore the other things in the Scriptures, “these ought ye to have done, and not to leave the other undone” (Matthew: 23:23). The history and archaeology of the Bible should not be explained by the scholars who do not believe in the supernatural and then sell their books to our young people, who are left with the impression the Bible is not trustworthy.

Some pretend it does not matter if one who writes about the Bible believes in miracles, the creation account, the resurrection, or even God, but this would be as naive as to believe that opposing political parties are unbiased when explaining each other’s views. Any researcher should at least study the Book that claims to be God’s Word and books written by those who believe in it. It only takes one small light at an exit door to show the way out of unbelief and error.

It is my sincere hope that, even with my limitations in this subject, God will be honored and His Name lifted up. “But there is a God in heaven that revealeth secrets…” (Daniel 2:28). I gladly, therefore, give Him credit for all that is right in this book, but like anyone, I certainly could have made mistakes (hopefully only small ones). There are, however, some things in this book, many things, which I have not read anywhere else on this subject.

What good will it do? I suppose someone could have asked that when Moses first brought the Ten Commandments down off Mt. Sinai, and three thousand people died because of their idolatry (Exodus 32:28).

The Bible says, “If they hear not Moses and the prophets, neither will they be persuaded, though one rose from the dead” (Luke 16:31). Some believe it is a waste of time to show people evidence to get them to believe, for if they believe not the Bible (“Moses and the prophets”), even if someone rose from the dead, they would not believe. This application was not meant for everyone. Lazarus rose from the dead, and “many of the Jews went away, and believed on Jesus” (John 12:9-11). God is not obligated to do this, nor is He our personal magician to work miracles for us at our will. But when He wants, there are times when He will do things such as the resurrection of Lazarus or smaller things to help the unbelief of some. And it is true that if someone does not want to believe, he will not, even if God works a miracle. We are told not to cast our “pearls before swine.” The chief priests did not believe when Lazarus was raised from the dead. Instead, they wanted to kill him (John 12:10). And it is more blessed to believe without seeing Lazarus or Christ raised from the dead, yet the Lord said, “Thomas, because thou hast seen me, thou hast believed…” (John 20:29). I am not teaching you should seek a sign (Matthew 12:39), nor do I know how many this would help, or for whom God would allow such. But the Apostle Paul would have never been saved by preaching alone. He had to be “knocked off his high horse” (Acts 9:3-6) before he would look up. With this said, what is wrong with trying to explain some things to people and giving them reasons to believe? The field of archaeology has been used by some to turn people away from the truth of God’s Word. There are books that will strengthen your faith, and there are books with “oppositions of science falsely so called” (I Timothy 6:20–21) that will take your faith away (I Timothy 6:20, Colossians 2:8). Many of the reasons I will give, come right out of the Bible, and these things were not written in vain, so hopefully, they will show how accurate God’s Word is.

My purpose is not to try and prove the Bible; it is true already. “All scripture is given by inspiration of God…” (II Timothy 3:16). Ultimately, faith comes from the Bible (Romans 10:17), not from artifacts buried in the sand. I looked for the route of the Exodus not to see if it was true, but because I already believed it was true.

“And the people came up out of Jordan on the tenth day of the first month, and encamped in Gilgal, in the east border of Jericho. And those twelve stones, which they took out of Jordan, did Joshua pitch in Gilgal. And he spake unto the children of Israel, saying, When your children shall ask their fathers in time to come, saying, What mean these stones? Then ye shall let your children know, saying, Israel came over this Jordan on dry land. For the LORD your God dried up the waters of Jordan from before you, until ye were passed over, as the LORD your God did to the Red sea, which he dried up from before us, until we were gone over: That all the people of the earth might know the hand of the LORD, that it is mighty: that ye might fear the LORD your God for ever” (Joshua 4:19–24).

It will be noticed that I am quoting from books that were published before 1923 (public domain). In a few cases, some were published after 1923, but their copyright was not renewed. In other cases, my quotes fall under “fair use” as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law, which says, “the reproduction of a particular work may be considered fair, such as criticism, comment…” My quotes of this type are all less than one sentence. It sounds as if it would be easy to get permission from others to quote their books, but not if they believe differently than you about the Exodus. Most of my requests to quote a source received no response. I am not saying this to complain, it is understandable. But I do not want the readers to think they are somehow missing out on the most up-to-date information. I, of course, read all the information I could find, both old and new, pro and con, and surprisingly, in most cases, the older works were more helpful and interesting, especially the ancient writings of the Jews and classical writers.

Miles Per Day

The encampments of the children of Israel are found in their proper order, with a reasonable distance traveled between them and an accessible route for their multitude.

How many miles a day could such a multitude have traveled with wagons (Numbers 7:3–8), children, the elderly, flocks, and all? For those who say Israel could not have traveled more than five or six miles a day because of the need to graze their herds and flocks, they need only look to the covered wagon trains and cattle drives of the western US. Wagon trains, unless hindered by forest, could travel twelve to sixteen miles a day. Cattle drives are said to have averaged fifteen miles a day or more, and their cattle actually gained weight at this pace. Their cattle grazed at noon and at night. Though it was not the norm, Barnes’ Notes on the Bible makes an interesting comment about miles per day from Genesis 31:20–24, saying it “would give him twelve days to travel three hundred English miles.” That would be twenty-five miles a day with children and herds. In truth, they (Jacob and his family) were fleeing from Laban, pushing themselves, but this shows that it was possible, and they sustained it for twelve days.

Western sheep cannot be compared to the sturdy Bedouin sheep of the Middle East. The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) website on Bedouin flocks, “Awassi sheep,” said, “flocks may be driven for as much as 35 km (21.75 miles) in 24 hours” (Williamson, 1949). http://www.fao.org/docrep/011/aj003e/AJ003E05.htm#fg21

The longest day’s march we have on the Exodus route is seventeen miles. The rate of fourteen miles a day was about the average on our route in the Eastern Desert of Egypt. There are, however, some scholars who want us to believe the average distance traveled was barely five miles a day, or that Israel traveled the absurd distance of sixty, seventy or more miles a day.

The children of Israel were prepared for this journey, being slaves used to hard work and rough living conditions, and at the start of their journey “there was not one feeble person among their tribes” (Psalms 105:37). In the same chapter, verse 39, it said the cloudy pillar that led them was as a “covering,” which would have given shade during the day on the hot desert and made it possible for them to travel at night. “And the LORD went before them by day in a pillar of a cloud, to lead them the way; and by night in a pillar of fire, to give them light; to go by day and night” (Exodus 13:21, Deuteronomy 1:33).

There are two variables in these miles-per-day averages. We do not know all the stops the Israelites made, nor do we know how long they stayed at each stop to rest. There are two times the Bible says Israel went three days, but only one stop is named (Exodus 15:22 and Numbers 10:33). They would have stopped each day, but no name is given for an encampment except the last one, probably because nothing exceptional happened at these stops or no name existed there. (In the desert, one would not expect to find a name at each location.) But this means there were most likely other stops not mentioned, and we learn that at the third place named after leaving Mount Sinai, forty days had gone by. Three days to get to Taberah (Numbers 10:33), thirty days of eating flesh at Kibroth-hattaavah (Numbers 11:19–20), and at least a week at Hazeroth, where Miriam (Numbers 12:15) had to wait outside the camp. My point is, they were able to rest sometimes between days of travel, which would make a big difference in how many miles a day they averaged. It should not be assumed, therefore, that it was only a one-day’s march between all the stations or that they only passed one night at each encampment.

Maps. The primary map used is an 1844 map by John Arrowsmith, used by permission from the David Rumsey Map Collection, www.davidrumsey.com. I like this map, as it is easy to read and has most of the place names on it where Israel traveled. There are other maps, also from the David Rumsey Collection, which will be used because they show a better view of the landscape. The 1844 map received the place names for the Eastern Desert from Sir John Gardner Wilkinson.2 Sir Wilkinson made the original survey of the Eastern Desert and was the first to copy many of these names; I will, therefore, be using a number of his quotes.

It will be important to keep in mind the geography of Egypt. “Lower” Egypt is in the north, and “Upper” Egypt is in the south! The Nile flows from south to the north, the opposite of the Mississippi river; it is easy to forget this and become confused. As to pictures of burnt mountains, inscriptions, pillars, etc., these will be addressed later in this book. The first time I quote an ancient writer, besides giving his name, I will also give the approximate date he wrote and what his occupation was, but thereafter, unless helpful to the point being made, I may give only the name. Also, as much as possible, I wanted this work to be in the form of a story, not a phone book with only names and addresses, so though I believe it is well researched, it will not be all technical details.

ENDNOTES

1. John Murray. Sir John Gardner Wilkinson. A Handbook for Travelers in Egypt (1867), 42.

2. The 1844 map by John Arrowsmith has written on the Red Sea area the following: “The detail in the Egyptian Desert between Suez & Kenneh is copied from an original M.S. Drawing by J. Wilkinson, Esq.

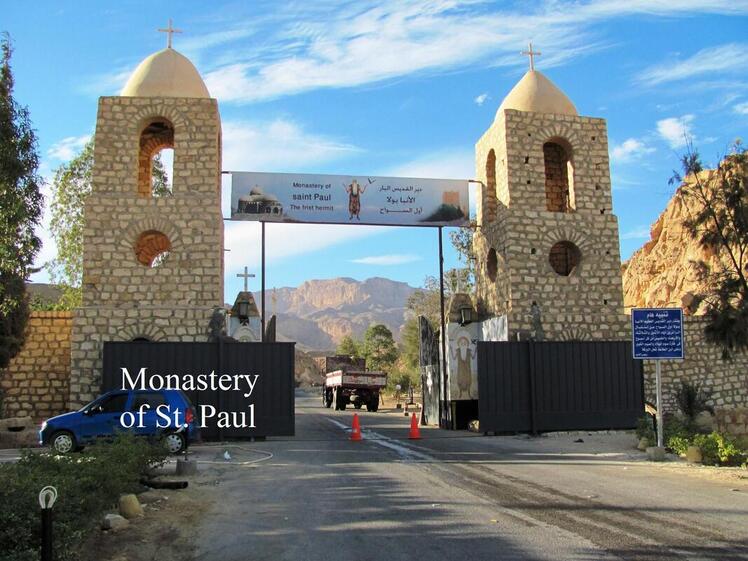

On the way to Mount Sinai.

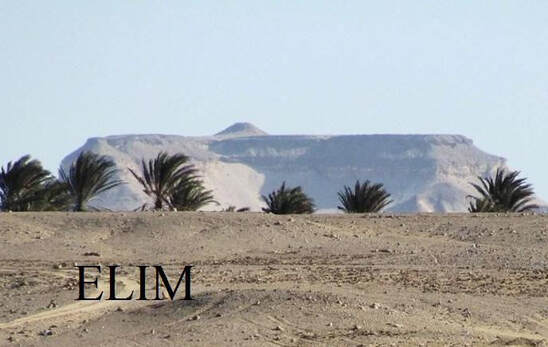

Seven encampments (stations)—Succoth, Etham, Marah, Wilderness of Sin, Rephidim, Kibroth-hattaavah and Libnah—either had some uncertainty with their location or problem with the meaning of the Arabic name and will be labeled “possible.” But even these seven encampments are not guesses; they are still in the right order and with good reasons for choosing them as the right encampments. There are, however, nine encampments I believe are more than coincidences: (1) Elim, (2) Red Sea (the second time the Israelites encamped by it), (3) Dophkah, (4) Alush, (5) Wilderness of Sinai, (6) Hazeroth, (7) Rithmah, (8) Rimmon-parez, and (9) Kadesh-barnea. This is not counting Mount Seir or Mount Sinai, as Israel did not camp on these mountains but only near them.

All encampments are given in the order found in the Bible, and nine are either (1) on the map that will be used, or (2) names that describe them are on the map, or (3) from historical documents that placed them at that location.

The encampments of the children of Israel are found in their proper order, with a reasonable distance traveled between them, an accessible route for a multitude with “wagons” (Numbers 7:3–8), a logical direction, and even falling on a known ancient route. (I was not zigzagging my way through the desert trying to pick up place names.) I believe any researcher or layman who looks at the sites of these nine encampments, especially when taken together, will conclude these are more than coincidences, and in some cases simply amazing! For the location of Mount Sinai, I have evidence from a pharaoh of Egypt who left his inscription at the mountain and then returned to Egypt and recorded his trip there in Egyptian hieroglyphic! Read and see if this book lives up to my claims.

The meanings of many of these place names from the route of the Exodus are anything but vague, and in fact, some of the names border on the bizarre and if found, would only help confirm the route, as Rimmon-parez = “pomegranate of the breach”, or Kibroth-hattaavah = “graves of lust”, or Dophkah = “knocking”.

For those wondering if this book will explain the locations of Midian and Arabia and why they would work with the Eastern Desert of Egypt, the answer is, yes! The “eleven days” from Mount Horeb (Sinai) to Kadesh (Deuteronomy 1:2) will be explained and shown on a map. I wanted to demonstrate that I have the biblical Mount Sinai, which I believe necessitates showing that the eleven days of travel fit with Kadesh and Mount Seir, as given in this book, and is why the route was worked up to these locations.

Where to look. There is much more historical and archaeological information available for Memphis, Saqqara, and the Nile Delta than for the Eastern Desert of Egypt. There are, however, a number of Jewish sources that give information about this part of the Exodus encampments. The names of these encampments were, of course, helpful, along with the extra information found in the Bible, and these all helped to guide our search. I also received much help from reading the writings of early travelers in the Eastern Desert. And when I say I found such and such a place, it means only the application of the place name for the route of the Exodus, not the actual discovery of the site. When I use the words us, we, and our, they will usually refer to my wife, Nancy, and me.

Dedicated to the nation of Israel.

Thank you for preserving the first and second commandment (Deuteronomy 5:7–10), without which the world would still be worshiping a multitude of gods and their idols. God said, “Blessed is he that blesseth thee, and cursed is he that curseth thee” Amen! (Numbers 24:5–9).

Seven encampments (stations)—Succoth, Etham, Marah, Wilderness of Sin, Rephidim, Kibroth-hattaavah and Libnah—either had some uncertainty with their location or problem with the meaning of the Arabic name and will be labeled “possible.” But even these seven encampments are not guesses; they are still in the right order and with good reasons for choosing them as the right encampments. There are, however, nine encampments I believe are more than coincidences: (1) Elim, (2) Red Sea (the second time the Israelites encamped by it), (3) Dophkah, (4) Alush, (5) Wilderness of Sinai, (6) Hazeroth, (7) Rithmah, (8) Rimmon-parez, and (9) Kadesh-barnea. This is not counting Mount Seir or Mount Sinai, as Israel did not camp on these mountains but only near them.

All encampments are given in the order found in the Bible, and nine are either (1) on the map that will be used, or (2) names that describe them are on the map, or (3) from historical documents that placed them at that location.

The encampments of the children of Israel are found in their proper order, with a reasonable distance traveled between them, an accessible route for a multitude with “wagons” (Numbers 7:3–8), a logical direction, and even falling on a known ancient route. (I was not zigzagging my way through the desert trying to pick up place names.) I believe any researcher or layman who looks at the sites of these nine encampments, especially when taken together, will conclude these are more than coincidences, and in some cases simply amazing! For the location of Mount Sinai, I have evidence from a pharaoh of Egypt who left his inscription at the mountain and then returned to Egypt and recorded his trip there in Egyptian hieroglyphic! Read and see if this book lives up to my claims.

The meanings of many of these place names from the route of the Exodus are anything but vague, and in fact, some of the names border on the bizarre and if found, would only help confirm the route, as Rimmon-parez = “pomegranate of the breach”, or Kibroth-hattaavah = “graves of lust”, or Dophkah = “knocking”.

For those wondering if this book will explain the locations of Midian and Arabia and why they would work with the Eastern Desert of Egypt, the answer is, yes! The “eleven days” from Mount Horeb (Sinai) to Kadesh (Deuteronomy 1:2) will be explained and shown on a map. I wanted to demonstrate that I have the biblical Mount Sinai, which I believe necessitates showing that the eleven days of travel fit with Kadesh and Mount Seir, as given in this book, and is why the route was worked up to these locations.

Where to look. There is much more historical and archaeological information available for Memphis, Saqqara, and the Nile Delta than for the Eastern Desert of Egypt. There are, however, a number of Jewish sources that give information about this part of the Exodus encampments. The names of these encampments were, of course, helpful, along with the extra information found in the Bible, and these all helped to guide our search. I also received much help from reading the writings of early travelers in the Eastern Desert. And when I say I found such and such a place, it means only the application of the place name for the route of the Exodus, not the actual discovery of the site. When I use the words us, we, and our, they will usually refer to my wife, Nancy, and me.

Dedicated to the nation of Israel.

Thank you for preserving the first and second commandment (Deuteronomy 5:7–10), without which the world would still be worshiping a multitude of gods and their idols. God said, “Blessed is he that blesseth thee, and cursed is he that curseth thee” Amen! (Numbers 24:5–9).

Chapter One

Where was Mount Sinai

The location of Mount Sinai.

1) By the country of Troglodytes (Josephus (1st century, Antiquities, II, 11:1–2).

2) Near the land of Midian (Exodus 2:15).

3) And in Arabia (Galatians 4:25).

Troglodytes? Josephus calls the area that Moses went to the land of “Midian” of the “Troglodytes” and on the “Red Sea.” Josephus, when giving the account of Moses meeting the daughters of Jethro (the priest of Midian, Exodus 3:1), said, “These virgins, who took care of their father’s flocks, which sort of work it was customary and very familiar for women to do in the country of the Troglodytes….”2

The name Troglodytes (also spelled without the l, Trogodite), means “cave goers” or “cave dwellers,” and many groups at different times lived in caves, but the “country” of Troglodytes was in the Eastern Desert of Egypt. “Between Egypt and the Red Sea were nations of Arabians called Troglodyte…”1 (Sir Isaac Newton, 17th century, mathematician, astronomer).

Some have thought that Josephus was referring to the ancient location of Petra, because it had many manmade caverns. But Josephus knew of Petra and speaks of it by name a number of times in his books, but never calls it the land or country of Troglodytes. Josephus said, “And when he came to a place which the Arabians esteem their metropolis, which was formerly called Arce [not Troglodytes], but has now the name of Petra….”3 Josephus would have used the name Troglodytes as did the classical writers (ancient Greek and Roman writers) of his time period, and they have the “country of Troglodytes” on the African side of the Red Sea, or the Eastern Desert of Egypt.

The land of Troglodytes started at the head of the Gulf of Suez and was on the west side, going south to Somalia. The name “Trogodytesca” can still be found on some modern maps today at the city of Berenice on the west side of the Red Sea.

Some have thought that the Troglodytes lived only south of the city of Berenice, but the classical writers clearly have the country of Troglodytes starting by the present-day city of Suez and extending south to the Horn of Africa (Somalia). Diodorus (Greek historian, 1st century BC) said, “first of all we shall take the right side [west side, from the apex of the Gulf of Suez going south], the coast of which is inhabited by tribes of the Trogodytes as far inland as the desert. In the course of the journey, then, from the city of Arsinoê [the present city of Suez] along the right mainland….”5 Strabo (Greek geographer, 1st century AD) locates them also in this area, “As one sails from the City of Heroes [north of Suez] along the Trogodytesc country….”6 So when Josephus gives the account of Moses meeting the daughters of Jethro, and says the location was “in the country of the Troglodytes...” he and the classical writers were talking about the Eastern Desert of Egypt.

The land of Midian was in Saudi Arabia, but was it anywhere else? “Now Moses kept the flock of Jethro his father-in-law, the priest of Midian: and he led the flock to the backside of the desert, and came to the mountain of God, even to Horeb” (Horeb is in reference to Sinai, Exodus 3:1). There are many such verses as the one given here and it is not disputed that Moses lived in Midian (spelled Madian in the New Testament, Acts 7:29), but where was the land of Midian located? Most maps have the land of Midian on the east side of the Gulf of Aqaba.

I know of no maps that locate Midian in the Eastern Desert of Egypt, but it can be traced there. Others could have done this already, but as I said in the beginning of the book, they are forced to look elsewhere for where Moses and Israel traveled because they show Israel leaving from the East Delta and therefore must place the sea crossing east of that, either at the Bitter Lakes, Gulf of Suez, or Gulf of Aqaba. Again, this is why they are not looking in the Eastern Desert of Egypt for Mount Sinai. Because if the Israelites crossed the sea at either the Bitter Lakes or one of the gulfs, then they would not have crossed the sea again in order to get to the Eastern Desert.

“And the sons of Midian; Ephah, and Epher, and Hanoch, and Abida, and Eldaah. All these were the children of Keturah” (Genesis 25:4). Please observe the difference in spelling when hundreds of years later Josephus, writing in the Greek language, quoted from this same passage, “The sons of Madiau were Ephas, and Ophren, and Anoch, and Ebidas, and Eldas. Now, for all these sons and grandsons, Abraham contrived to settle them in colonies; and they took possession of Trogodytes, and the country of Arabia the Happy, as far as it reaches to the Red Sea.”7 There are a few who have thought Josephus was saying that Troglodytes was in the country of “Arabia the Happy,” which is on the east side of the Red Sea. But he said that Abraham’s descendants through Keturah “took possession of Trogodytes, and the country of Arabia the Happy….” They became two countries: Troglodytes and Arabia the Happy.

From the Scriptures we see that the Midianites lived in different locations. Israel, during the Exodus, left the Midianites, who dwelled close by Mount Sinai (Exodus 3:1, 18:1–5), and some Midianites departed with Israel (Judges 1:16, Numbers 10:29–32). And on their way to the Promised Land, they met up with a group of Midianites who were allied with Moab against them (Numbers 22:3–7). In I Kings 11:17–18, some Edomites fled to Egypt, and we are told they “arose out of Midian,” then to Paran and then to Egypt. If one insists that Midian was only in Saudi Arabia, then these men from the land of Edom made a pointless trip, far out of their way, to go to Egypt.